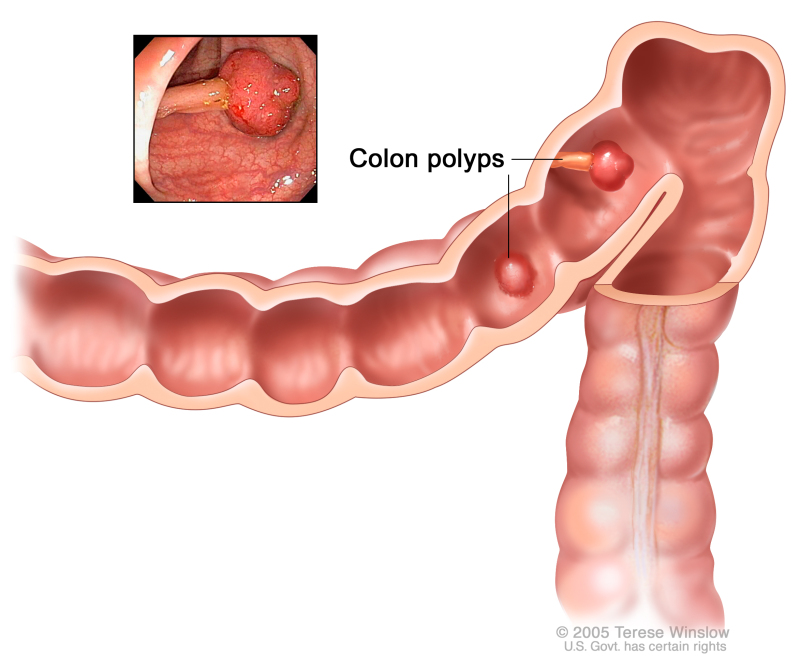

Colon cancer refers to a slowly developing cancer that begins as a tumor or tissue growth on the inner lining of the rectum or colon [rx]. If this abnormal growth, known as a polyp, eventually becomes cancerous, it can form a tumor on the wall of the rectum or colon, and subsequently grow into blood vessels or lymph vessels, increasing the chance of metastasis to other anatomical sites [rx,rx]. Of the cancers that begin in the colorectal region, the vast majority (over 95%) are classified as adenocarcinomas [rx]. These begin in the mucus-making glands lining the colon and rectum [rx,rx]. Other less-common cancers of the colorectal region include carcinoid tumors (which begin in hormone-producing intestinal cells), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (which form in specialized colonic cells known as interstitial cells of Cajal), lymphomas (immune system cancers that form in the colon or rectum), and sarcomas (which typically begin in blood vessels but occasionally form in colorectal walls) [rx,rx]

Types of Colon Cancer

Recently, six independent classification systems coalesced into four consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) with distinguishing features:

-

CMS1 (MSI- immune, 14%) – hypermutated burden, dMMR, microsatellite unstable and strong immune activation

-

CMS2 (canonical, 37%) – high chromosomal instability, epithelial, marked WNT and MYC signaling activation

-

CMS3 (metabolic, 13%) – epithelial and evident metabolic dysregulation, KRAS mutation

-

CMS4 (mesenchymal, 23%) – CpG hypermethylation, prominent transforming growth factor-beta activation, stromal invasion and angiogenesis.

CMSs classification had prognostic value, CMS1 good, CMS4 poor and CMS2/3 intermediate. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can occur in the colon. See the PDQ summary on Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment for more information.

Causes of Colon Cancer

The most common forms of inherited colon cancer syndromes are

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) – HNPCC, also called Lynch syndrome, increases the risk of colon cancer and other cancers. People with HNPCC tend to develop colon cancer before age 50.

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) – FAP is a rare disorder that causes you to develop thousands of polyps in the lining of your colon and rectum. People with untreated FAP have a greatly increased risk of developing colon cancer before age 40.

- Age – Around 1 in 20 people develop bowel cancer. Almost 18 out of 20 cases of bowel cancer in the UK are diagnosed in people over the age of 60.

- Family history – Having a family history of bowel cancer in a first-degree relative – a mother, father, brother or sister – under the age of 50 can increase your lifetime risk of developing the condition yourself.I f you’re particularly concerned that your family’s medical history may mean you’re at an increased risk of developing bowel cancer, it may help to speak to your GP. If necessary, your GP can refer you to a genetics specialist, who can offer more advice about your level of risk and recommend any necessary tests to periodically check for the condition

- Diet – A large body of evidence suggests a diet high in red and processed meat can increase your risk of developing bowel cancer. For this reason, the Department of Health advises people who eat more than 90g (cooked weight) a day of red and processed meat cut down to 70g a day. There’s also evidence that suggests a diet high in fibre could help reduce your bowel cancer risk.

- Smoking – People who smoke cigarettes are more likely to develop bowel cancer, as well as other types of cancer and other serious conditions, such as heart disease

- Alcohol – Drinking alcohol has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of bowel cancer, particularly if you regularly drink large amounts

- Obesity – Being overweight or obese is linked to an increased risk of bowel cancer, particularly in men. If you’re overweight or obese, losing weight may help lower your chances of developing the condition.

- Inactivity – People who are physically inactive have a higher risk of developing bowel cancer.

- Having a family history of colon or rectal cancer in a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child).

- Having a personal history of cancer of the colon, rectum, or ovary.

- Having a personal history of high-risk adenomas (colorectal polyps that are 1 centimeter or larger in size or that have cells that look abnormal under a microscope).

- Having inherited changes in certain genes that increase the risk of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer).

- Having a personal history of chronic ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease for 8 years or more.

- Having three or more alcoholic drinks per day.

- Smoking cigarettes.

- Being black.

- Being obese.

Older age is the main risk factor for most cancers. The chance of getting cancer increases as you get older.

Symptoms of Colon Cancer

- A Change in Bowel Habits – Including diarrhea, constipation, a change in the consistency of your stool or finding your stools are narrower than usual

- Persistent Abdominal Discomfort – Such as cramps, gas, or pain and/or feeling full, bloated or that your bowel does not empty completely

- Rectal Bleeding – Finding blood (either bright red or very dark) in your stool

- Weakness or Fatigue – Can also accompany losing weight for no known reason, nausea or vomiting

- A persistent change in bowel habit – going more often, with looser stools and sometimes tummy (abdominal) pain

- Blood in the stools without other piles (hemorrhoids) symptoms – this makes it unlikely the cause is hemorrhoids

- Abdominal pain, discomfort or bloating always brought on by eating – sometimes resulting in a reduction in the amount of food eaten and weight loss

- Constipation – where you pass harder stools less often, is rarely caused by serious bowel conditions. Colorectal cancer symptoms can also be associated with many other health conditions. Only a medical professional can determine the cause of your symptoms. Early signs of cancer often do not include pain. It is important not to wait before seeing a doctor. Early detection can save your life.

-

A change in bowel habits.

-

Blood (either bright red or very dark) in the stool.

-

Diarrhea, constipation, or feeling that the bowel does not empty all the way.

-

Stools that are narrower than usual.

-

Frequent gas pains, bloating, fullness, or cramps.

- Rectal bleeding or blood in the stool

- Abdominal pain, cramps, bloating, or gas

- Pain during bowel movements

- Continual urges to defecate

- Weakness and fatigue

- Unexplained weight loss

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Iron deficiency anemia

-

Feeling very tired.

-

Vomiting.

Diagnosis of Colon Cancer

The following tests and procedures may be used

-

Physical exam and history – An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

-

Digital rectal exam – An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

-

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) – A test to check stool (solid waste) for blood that can only be seen with a microscope. A small sample of stool is placed on a special card or in a special container and returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing. Blood in the stool may be a sign of polyps, cancer, or other conditions.

There are two types of FOBTs

- Guaiac FOBT – The sample of stool on the special card is tested with a chemical. If there is blood in the stool, the special card changes color. A guaiac fecal occult blood test (FOBT) checks for occult (hidden) blood in the stool. Small samples of stool are placed on a special card and returned to a doctor or laboratory for testing.

-

Immunochemical FOBT – A liquid is added to the stool sample. This mixture is injected into a machine that contains antibodies that can detect blood in the stool. If there is blood in the stool, a line appears in a window in the machine. This test is also called fecal immunochemical test or FIT.

-

Barium enema – A series of x-rays of the lower gastrointestinal tract. A liquid that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound) is put into the rectum. The barium coats the lower gastrointestinal tract and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called a lower GI series.

-

Sigmoidoscopy – A procedure to look inside the rectum and sigmoid (lower) colon for polyps (small areas of bulging tissue), other abnormal areas, or cancer. A sigmoidoscope is inserted through the rectum into the sigmoid colon. A sigmoidoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

-

Colonoscopy – A procedure to look inside the rectum and colon for polyps, abnormal areas, or cancer. A colonoscopy is inserted through the rectum into the colon. A colonoscopy is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

-

Virtual colonoscopy – A procedure that uses a series of x-rays called computed tomography to make a series of pictures of the colon. A computer puts the pictures together to create detailed images that may show polyps and anything else that seems unusual on the inside surface of the colon. This test is also called colonography or CT colonography.

-

Biopsy – The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer.

Stages of Colon Cancer

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

In stage 0, abnormal cells are found in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the colon wall. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue. Stage 0 is also called carcinoma in situ.

Stage I

Stage I colon cancer. Cancer has spread from the mucosa of the colon wall to the submucosa or to the muscle layer. In stage I colon cancer, cancer has formed in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the colon wall and has spread to the submucosa (layer of tissue next to the mucosa) or to the muscle layer of the colon wall.

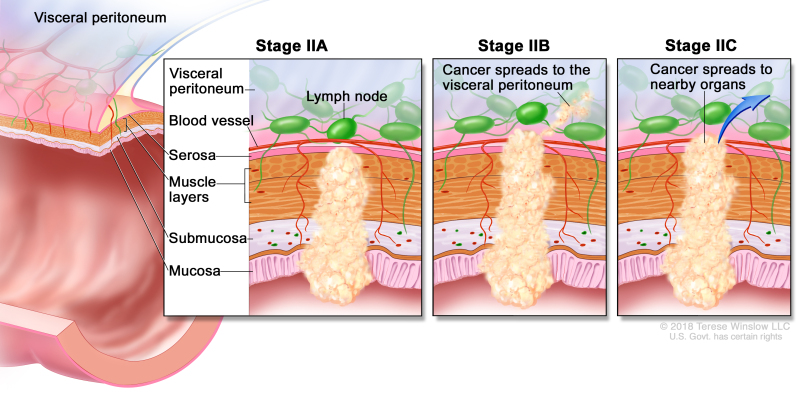

Stage II

Stage II colon cancer. In stage IIA, cancer has spread through the muscle layer of the colon wall to the serosa. In stage IIB, cancer has spread through the serosa but has not spread to nearby organs. In stage IIC, cancer has spread through the serosa to nearby organs.

Stage II colon cancer is divided into stages IIA, IIB, and IIC.

-

Stage IIA – Cancer has spread through the muscle layer of the colon wall to the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall.

-

Stage IIB – Cancer has spread through the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall to the tissue that lines the organs in the abdomen (visceral peritoneum).

-

Stage IIC – Cancer has spread through the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall to nearby organs.

Stage III

Stage III colon cancer is divided into stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC.

Stage IIIA colon cancer. Cancer has spread through the mucosa of the colon wall to the submucosa and may have spread to the muscle layer, and has spread to one to three nearby lymph nodes or tissues near the lymph nodes. OR, cancer has spread through the mucosa to the submucosa and four to six nearby lymph nodes.

In stage IIIA, cancer has spread

-

through the mucosa (innermost layer) of the colon wall to the submucosa (layer of tissue next to the mucosa) or to the muscle layer of the colon wall. Cancer has spread to one to three nearby lymph nodes or cancer cells have formed in tissue near the lymph nodes; or

-

through the mucosa (innermost layer) of the colon wall to the submucosa (layer of tissue next to the mucosa). Cancer has spread to four to six nearby lymph nodes.

Stage IIIB colon cancer. Cancer has spread through the muscle layer of the colon wall to the serosa or has spread through the serosa but not to nearby organs; cancer has spread to one to three nearby lymph nodes or to tissues near the lymph nodes. OR, cancer has spread to the muscle layer or to the serosa, and to four to six nearby lymph nodes. OR, cancer has spread through the mucosa to the submucosa and may have spread to the muscle layer; cancer has spread to seven or more nearby lymph nodes.

In stage IIIB, cancer has spread

-

through the muscle layer of the colon wall to the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall or has spread through the serosa to the tissue that lines the organs in the abdomen (visceral peritoneum). Cancer has spread to one to three nearby lymph nodes or cancer cells have formed in tissue near the lymph nodes; or

-

to the muscle layer or to the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall. Cancer has spread to four to six nearby lymph nodes; or

-

through the mucosa (innermost layer) of the colon wall to the submucosa (layer of tissue next to the mucosa) or to the muscle layer of the colon wall. Cancer has spread to seven or more nearby lymph nodes.

Stage IIIC colon cancer. Cancer has spread through the serosa of the colon wall but not to nearby organs; cancer has spread to four to six nearby lymph nodes. OR, cancer has spread through the muscle layer to the serosa or has spread through the serosa but not to nearby organs; cancer has spread to seven or more nearby lymph nodes. OR, cancer has spread through the serosa to nearby organs and to one or more nearby lymph nodes or to tissues near the lymph nodes.

In stage IIIC, cancer has spread

-

through the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall to the tissue that lines the organs in the abdomen (visceral peritoneum). Cancer has spread to four to six nearby lymph nodes, or

-

through the muscle layer of the colon wall to the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall or has spread through the serosa to the tissue that lines the organs in the abdomen (visceral peritoneum). Cancer has spread to seven or more nearby lymph nodes; or

-

through the serosa (outermost layer) of the colon wall to nearby organs. Cancer has spread to one or more nearby lymph nodes or cancer cells have formed in tissue near the lymph nodes.

Stage IV

Stage IV colon cancer. Cancer has spread through the blood and lymph nodes to other parts of the body, such as the lung, liver, abdominal wall, or ovary. Stage IV colon cancer is divided into stages IVA, IVB, and IVC.

-

Stage IVA – Cancer has spread to one area or organ that is not near the colon, such as the liver, lung, ovary, or a distant lymph node.

-

Stage IVB – Cancer has spread to more than one area or organ that is not near the colon, such as the liver, lung, ovary, or a distant lymph node.

-

Stage IVC – Cancer has spread to the tissue that lines the wall of the abdomen and may have spread to other areas or organs.

Diagnosis

In HICs, persons with CRC can present in several ways

-

First, cancer can be detected as a result of screening. When gFOBT, FIT, or FS is used as the initial screening test, colonoscopy is undertaken as a diagnostic test to evaluate those with an abnormal screening test. During the colonoscopy, polyps are removed and masses or other suspicious lesions are either removed or biopsied to establish a pathological diagnosis.

-

Second, cancer can be detected when an individual undergoes colonoscopy to evaluate large bowel symptoms, such as rectal bleeding, anemia, or a change in bowel habits.

-

Third, some individuals may present as an emergency, such as a large bowel obstruction, in which case cancer may be diagnosed at surgery without prior diagnostic evaluation.

Endoscopic techniques for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer

High-definition white-light endoscopy

-

The current standard for colonoscopy, combining high-definition video endoscopes with high-resolution video screens

-

Provides a detailed image of the gastrointestinal mucosa

-

The advantage of routine endoscopy, the disadvantage that it provides no specific contrast for detection of neoplastic lesions

Chromoendoscopy

-

The use of a dye spray during gastrointestinal endoscopy to improve visualization

-

Improves detection of neoplastic lesions

-

Time-consuming to spray the complete colon

-

A new technique with dye incorporated into colon preparation is under investigation

Magnification endoscopy

-

Endoscope with zoom-lens in tip, which enables 6–150-fold enlargement of the mucosa

-

Can characterize and determine the extension of neoplastic lesions

-

Not suitable for screening of the complete colon

-

Can be combined with other methods

Narrow band imaging

-

A technique that can be built into white-light endoscopes

-

Filters light to two bands, with a wavelength of respectively 415 nm (blue) and 540 nm (green)

-

Longer wavelength light is less scattered and, therefore, penetrates deeper into the mucosa

-

Blue light enhances superficial capillaries, whereas the green light displays deeper, subepithelial vessels

-

Can characterize and determine the extension of neoplastic lesions

-

Does not increase neoplasia detection rates

Intelligent color enhancement (FICE) imaging (Fujinon) and iScan imaging (Pentax)

-

Similar techniques as narrow band imaging, but no filtering of the outgoing light

-

Instead, processes the reflected light

Autofluorescence endoscopy

-

A technique that can also be built into white-light endoscopes

-

Based on the principle that illumination with a specific blue wavelength light can lead to excitation of tissue, which then emits light with a longer wavelength

-

The wavelength of the emitted light is longer for neoplastic tissue

-

Can be used to search for neoplastic lesions

Endomicroscopy

-

The technique of extreme magnification endoscopy

-

Enables in vivo visualization of individual glands and cellular structures

-

Can evaluate neoplastic lesions

-

Not suitable for scanning larger mucosal surfaces

After colon cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the colon or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the colon or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment.

The following tests and procedures may be used in the staging process:

-

CT scan (CAT scan) – A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the abdomen, pelvis, or chest, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to x-ray machines. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

-

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) – A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the colon. A substance called gadolinium is injected into the patient through a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

-

PET scan (positron emission tomography scan) – A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

-

Chest x-ray – An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

-

Surgery – A procedure to remove the tumor and see how far it has spread through the colon.

-

Lymph node biopsy – The removal of all or part of a lymph node. A pathologist views the lymph node tissue under a microscope to check for cancer cells. This may be done during surgery or by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy.

- Complete blood count (CBC) – A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following: The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells. The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay: A test that measures the level of CEA in the blood. CEA is released into the bloodstream from both cancer cells and normal cells. When found in higher than normal amounts, it can be a sign of colon cancer or other conditions.

-

Colonoscopy – Colonoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. It has high diagnostic accuracy and can assess the location of the tumor. Importantly, the technique can enable simultaneous biopsy sampling and, hence, histological confirmation of the diagnosis and material for molecular profiling. Colonoscopy is also the only screening technique that provides both a diagnostic and a therapeutic effect. Removal of adenomas using endoscopic polypectomy can reduce cancer incidence and mortality[rx],[rx]–[rx].

-

Capsule endoscopy – Capsule endoscopy uses a wireless capsule device swallowed by the screenee and enables examination of almost the entire gastrointestinal tract without the use of conventional endoscopy[rx]. Capsule endoscopy is useful in diagnosing adenomas and colorectal cancer. The first-generation capsule endoscopy was found to be able to detect polyps ≥6 mm in size with a sensitivity of approximately 60% and specificity of >80%[rx]. Cancer detection was achieved in 74% patients with colorectal cancer[rx].

-

Fecal DNA – A cross-sectional study comparing the performance of a stool DNA prototype versus gFOBT versus colonoscopy reported that the stool DNA test detected a greater proportion of CRCs and CRCs plus adenomas with high-grade dysplasia than the gFOBT, 51.6 percent vs. 12.9 percent, and 40.8 percent vs. 14.1 percent, respectively. However, the majority of neoplastic lesions was not detected by either test. Since then, stool DNA technology has continued to evolve [rx]. A large-scale, cross-sectional study (DeeP-C) of a next-generation stool DNA test has recently been published [rx] and indicates 92.3 percent sensitivity for the detection of CRC and 42.4 percent sensitivity for the detection of advanced adenomas.

-

Computed Tomographic Colonography (CTC) – CTC is a computerized tomography examination of the abdomen and pelvis in which imaging information, when processed with special imaging software, provides images of the colon and rectum. Images are also produced of structures outside the colon (extracolonic findings). The technique requires bowel preparation and colonic insufflation, but not conscious sedation, as is generally required for colonoscopy.

-

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (FS) – FS is an endoscopic procedure in which a flexible fiberoptic instrument is used to examine the rectum and lower (distal) colon, unlike colonoscopy, which examines the rectum and total (upper and lower) colon. Cancers and precancerous lesions, such as adenomas observed in this area, can be removed or biopsied. Large-scale RCTs of FS, coupled with colonoscopy for those who test positive, have shown reductions in CRC incidence

-

Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) – FIT is a stool test that uses an antibody against human globin, the protein part of hemoglobin. A positive FIT is specific for human blood. There are no large-scale RCTs that have evaluated FIT with long-term follow-up and CRC mortality as the outcome, although two RCTs are underway.

Treatment of Colon Cancer

-

Avoiding immune destruction – immune suppression in tumor microenvironment by induction of local cytokines

-

Evading growth suppressors – mutation and downregulation of growth-inhibiting factors and their receptors

-

Genome instability and mutation – inactivation of DNA repair mechanisms

-

Enabling replicative immortality – inhibition of mechanisms that induce senescence and induction of telomerase activity

-

Deregulating cellular energetics – aerobic glycolysis (Warburg phenomenon) and glutaminolysis

-

Tumor-promoting inflammation – induction of growth-promoting and angiogenesis-promoting factors by secreted proteins made by local inflammatory cells

-

Inducing angiogenesis – induction of the formation of new blood vessels

-

Resisting cell death – escape from autonomous and paracrine mediators of apoptosis and other forms of cell death (necrosis, necroptosis)

-

Activating invasion and metastasis remodeling – of extracellular matrix to promote cell motility and induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

-

Adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy became a standard of care in stage III Cca in the early 1990s by the first randomized clinical trial, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) C-01, to achieve a significant improvement in DFS and OS. Evidence from a subsequent NSABP C-03 trial demonstrated that fluorouracil (5-FU) combined with leucovorin (LV) provided a superior DFS and OS at three years with six months of adjuvant therapy over NSABP C-01 lomustine, vincristine, and 5-FU. For more than a decade, 5-FU/LV remained the standard in adjuvant therapy until oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and capecitabine (oral FU pro-drug) based combinations were utilized for the treatment of advanced CRC.

-

Oxaliplatin – was approved as part of adjuvant treatment for stage III Cca after the 2004 MOSAIC trial. Investigators randomly assigned patients who had undergone curative colon resection for stage II (40%) or III (60%) to receive FU/LV alone (LV 200 mg/m as a 2-hour infusion, followed by bolus FU 400 mg/m, and then a 22-hour infusion of FU 600 mg/m, every 2 weeks) or with oxaliplatin (FU/LV plus 85 mg/m day 1 every 14 days, a regimen termed FOLFOX4) for 6 months.

-

Neoadjuvant Therapy – The role of pre-operative chemotherapy for patients with Cca is currently on a phase III FOxTROT trial [rx] after promising results of their pilot study – The Foxtrot collaborative group randomized locally advanced resectable (T3 greater than 5 mm invasion beyond muscular propia and T4) candidates to 3 preoperative cycles of FOLFOX (O; 85 mg/m(2), LV; 175 mg, FU; 400 mg/m(2) bolus, then 2400 mg/m(2) by 46 hour infusion), surgery and nine additional cycles or surgery and 12 adjuvant cycles. Findings favored neo-adjuvant therapy with tumor regression (31% versus 2%), node-positive (1% versus 20%) and negative margins (4% versus 20%) resulting in a significant downstaging (p=0.04).

-

Systemic Therapy – More than half of all CRC patients will develop metastasis and the majority to the liver (80% to 90%). The prognosis for advanced non-resectable and metastatic CRC patients with best supportive care is poor by a MOS 5 to 6 months, except for a subset of patients with an oligo-metastatic hepatic or pulmonary patient that are potentially curable with peri-operative chemotherapy. The goals of systemic therapy for advanced non-resectable and metastatic CRC of therapy are palliation of symptoms, improvement of the quality of life and prolong survival.

Selected Landmark Clinical Trials

- Cytotoxic Chemotherapy – Fluorouracil-Leucovorin (FU/LV): An updated-meta analysis compared to FU-alone resulted in higher ORR (21% versus 11%) and 1-year OS (47% versus 37%) favoring FU/LV. The two most commonly used regimens in the United States include the Mayo regimen (bolus FU: 425 mg/m2 and LV: 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5 every 4 to 5 weeks) and the Roswell Park regimen (Bolus FU: 500 mg/m2 and LV: 500 mg/m2 administered weekly for 6 out of 8 weeks). Further improved by the de Gramont regimen (LV: 200 mg/m2 as a 2-hour infusion followed by bolus FU: 400 mg/m2 and 22-hour infusion FU: 600 mg/m2 for 2 consecutive days every 2 weeks) with significantly better ORR (33% vs 14%), PFS (7 versus 5 months) and OS (15.5 versus 14.2 months) with significantly less grade 3/4 toxicities (23.9% vs 11.1%) compared to the Mayo regimen.

- Capecitabine (CAP) – A phase III clinical trial by Hoff PM et al. prospectively randomly assigned patients to oral CAP (1250 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days every 21 days) or FU/LV (the Mayo regimen) resulting in non-inferior ORR (24.8% versus 15.5%), time to progression (TTP 4.3 versus 4.7 months) and MOS (12.5 versus 13.3 months), respectively. Common side effects of CAP included diarrhea (overlapping toxicities with irinotecan), hyperbilirubinemia and hand-foot syndrome. CAP has never been directly compared with infusional FU/LV (de Gramont regimen), CAPOX versus infusional FOLFOX has shown to be of similar efficacy in the treatment of advanced CRC, as shown by the phase TREE-1 trial and AIO trial. In the United States clinical practice, dose-reducing CAP by about 20% (1000 mg/m2) alone or in combination regimens does not appear to decrease the treatment efficacy, but it greatly improves the side effect profile of the treatment. Other alternative oral fluoropyrimidines not approved in the United States include S1-derived three different agents tegafur-uracil, gimeracil and oteracil, and raltitrexed.

- Irinotecan (IRI) – In a landmark phase II clinical trial, patients with FU-refractory mCRC were randomly assigned either single-agent IRI (300 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) or BSC, showed a significant 1-year OS (36% versus 14%) with improved quality of life (performance status, weight loss, and pain-free), respectively. Following this, three key trials were conducted to test the role of IRI versus FU/LV in the front-line setting. A three-arm trial compared three treatment regimens: the Roswell Park regimen, IRI plus FU/LV weekly bolus regimen (IFL or Saltz regimen); and IRI alone.

- Oxaliplatin (OXA) – OXA has very limited activity in CRC as a single agent thus not recommended unless synergist with fluoropyrimidines. In phase III trial, FU/LV (de Gramont regimen) was compared with or without OXA (OXA: 85 mg/m2 on day 1 over 2 hours FOLFOX4 regimen) as first-line therapy for patients with mCRC. FOLFOX4 regimen had significantly higher ORR (51% versus 22%), PFS (9 versus 6 months) but comparable mOS (16.2 versus 14.7 months) with more grade 3/4 neutropenia, diarrhea, and neurotoxicity. Because no overall survival benefit was achieved in these first-line trials, the FDA did not approve OXA for CRC until years later for second-line therapy that showed prolonged PFS and increased ORR compared with FU/LV for patients who experienced disease progression while receiving first-line IRI-regimens. The most important side effect and dose-limiting toxicity of OXA is neurotoxicity. It may present as an acute and reversible, cold-triggered sensory neuropathy, or a chronic dose-limiting cumulative sensory neurotoxicity.

- Irinotecan versus Oxaliplatin-based regimens – After encouraging results of previous trials conducted in the United States and Europe using OXA and IRI, the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG)/Intergroup trial N9741 performed a pivotal and practice-changing trial comparing FOLFOX4, the standard combination IFL and new IROX combination (OXA:85 mg/m plus IRI 200 mg/m, both on day 1 every 3 weeks). The N9741 results demonstrated the superiority of FOLFOX compared with IFL and IROX as first-line therapy for mCRC with ORR (45% versus 31% versus 36%), PFS (8.7 versus 6.9 versus 6.7 months) and mOS (19.5 versus 15 versus 17.3 months), respectively. The toxicity profile likewise favored FOLFOX, except for neurotoxicity. FOLFOX emerged as new standard first-line therapy with rapid and widespread adaptation in the United States.

VEGF Inhibitors

- Bevacizumab (BEV) – In randomized placebo-controlled phase III trial, IFL plus BEV (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks) was assessed in first-line therapy for mCRC. For the first time, the addition of an anti-VEGF inhibitor was validated as an efficacious antineoplastic treatment by significantly improving ORR (45% versus 35%), PFS (10.6 versus 6.2 months), and mOS (20.3 versus 15.6 months). This trial was the first phase III validation of an antiangiogenic agent as an effective treatment option in human malignancy. Subsequently, FOLFOX-BEV also showed to improve mOS in first-line (TREE-2 trial 23.7 versus 18.2 months) and second-line (ECOG 3200 trial 12.9 versus 10.8 months) settings.

- Aflibercept (AFL) – AFL was evaluated in the second-line setting among patients who had all progressed OXA-based with or without BEV first-line chemotherapy by the placebo-controlled phase III VELOUR trial. Patients randomly selected to receive FOLFIRI with AFL (4 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks) had a significant improvement in ORR (19.8% versus 11.1%), PFS (6.9 versus 4.7 months and MOS (13.5 versus 12.1 months). The aflibercept arm toxicity profile had an intensified rate of grade 3/4 diarrhea, mucositis, neutropenia, infection, and fatigue plus hypertension, proteinuria, hemorrhage, and arterial-venous thromboembolic events, usually seen in FOLFIRI-BEV second-line.

- Ramucirumab (RAM) – In a double-blind placebo-controlled phase III RAISE trial, the addition FOLFIRI-RAM (8mg/IV every two weeks) as second-line therapy for patients progressing with a FOLFOX-BEV improved PFS (5.7 versus 4.5 months) and MOS (13.3 versus 11.7 months). Grade 3/4 neutropenia, hypertension, diarrhea and fatigue was worse on the combination arm.

Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies

- Cetuximab (CET) – CET monotherapy (400 mg/m2 followed by a weekly infusion of 250 mg/m2) for patients who had experienced disease progression on prior FU, OXA and IRI-based therapy had an improved ORR (40% vs. 11%) and MOS (6.1 versus 4.6 months) compared to BSC. The EPIC and BOND trials proved PFS and ORR superiority of IRI-CET over IRI-alone on patients with prior IRI failure, without significantly improving survival. A large multicenter randomized phase III CRYSTAL trial, FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab in treatment naïve CRC patients, confirmed that selected KRAS wild-type patients have a significantly higher ORR, PFS, and MOS (23.5 versus 20 months). CET arm had higher-grade diarrhea, magnesium-wasting syndrome, infusion reaction and ocular-skin toxicity, last correlated to response rate.

- Panitumumab (PAN) – Single-agent PAN (6 mg/kg every 2 weeks) was compared to BSC in a large international phase III trial in chemotherapy-refractory mCRC patients. PAN had an ORR (37% similar to CET) and modest prolonged PFS (8 versus 7.3 weeks), but MOS was not increased likely because crossed over from BSC to the PAN arm. The ASPECT phase III trial compared head-to-head PAN versus CET monotherapies on chemotherapy-refractory patients and showed non-inferior mOS (10 months) with similar expected toxicity profile. FOLFOX4-PAN benefit in first-line setting was seen in phase III PRIME trial with mPFS improvement (9.6 versus 8 months) and trend for MOS (23.0 versus 19.7 months) not significant at 55 weeks follow up.

VEGF Inhibitors Versus Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies

- The FIRE-3 trial recruited treatment naïve mCRC KRAS exon2 wild-type patients and randomly assigned to receive FOLFIRI_CET or FOLFIRI-BEV. The primary endpoint of the trial, objective response rate analyzed by intention-to-treat analysis, was not reached. Although no difference in PFS was noted (CET 10 versus BEV 10.3 months), the MOS was significantly longer in the FOLFIRI-CET arm (CET 28.7 versus BEV 25.0 months; HR, 0.77; p = 0.017). An updated analysis, which accounted for additional mutations in KRAS exon 3 and 4, as well as NRAS mutations exon 2 and 3, demonstrated a longer MOS survival of 33.1 months for FOLFIRI-CET.

- In contrast, the U.S. Intergroup study, CALGB/South-west Oncology Group (SWOG) 80405 trial that compared FOLFOX or FOLFIRI (dealer’s choice) with CET compared with BEV as first-line therapy had no difference in MOS (30 versus 29.9 months, respectively), not even whit expanded RAS-mutated analysis.

- The preliminary retrospective analysis suggests that patients treated with CET for KRAS wild-type left-sided tumors MOS are significantly higher than right-sided counterpart by 33.3 versus 19.4 months, respectively. Combination therapy with VEGF inhibitors and anti-EGFRs monoclonal antibody have failed even detrimental in multiple trials (BOND-2, PACCE, CAIRO-2), thus not recommended.

Salvage Therapy for Refractory Disease

- Regorafenib (REG) – REG (160mg PO daily for three weeks of 4 weeks cycle) efficacy was investigated in a placebo-controlled, multicenter international, randomized, phase III CORRECT trial after progression of multiple therapies. REG compared with placebo had ORR (41% versus 15%), PFS (1.9 versus 1.7 months) and modest MOS benefit (6.4 versus 5.0 months) but significant (p = 0.0052). The observed toxicity profile with regorafenib was hand-foot skin reaction, fatigue, hypertension, diarrhea, and rash, with a 1.6% fatal hepatic failure. The CONCUR trial later confirmed REG benefit.

- Trifluridine-tipiracil (TAS-102) – the international, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized-controlled, phase III RECOURSE study of patients with refractory showed that TAS-102 (35 mg/m2 orally twice daily on days 1 through 5 and 8 to 12 of each 28-day cycle) improved ORR (44% versus 16%), DFS and MOS (7.1 versus 5.3 months); The most adverse event was neutropenia (38%), febrile neutropenia (4%) and one treatment-related death.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

- Pembrolizumab (PEM) – In a phase II study, PEM (10 mg/kg every 14 days) was given to 11 heavily pretreated patients with dMMR mCRC with a remarkable ORR of 71% and PFS rate of 67%. An expanded cohort of 54 patients, PEM showed OOR of 50% and an 89% disease control rate with the durable response for more than a year, not seen in pMMR CRC.

- Nivolumab (NIV) – In CheckMate-142, NIV (3mg/kg every 2 weeks) was given to 74 dMMR CRC patients resulted in 31% objective response, 69% disease control, and median duration response not reached at 12 months.

Radiation Therapy

- While a combination of radiation and chemotherapy may be useful for rectal cancer,[rx] its use in colon cancer is not routine due to the sensitivity of the bowels to radiation.[rx] Just as for chemotherapy, radiotherapy can be used in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting for some stages of rectal cancer.

Immunotherapy

- Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has been found to be useful for a type of colorectal cancer with mismatch repair deficiency and microsatellite instability.[rx][rx]Pembrolizumab is approved for advanced CRC tumors that are MMR deficient and have failed usual treatments.[rx]

- Most people who do improve, however, still worsen after months or years.[rx] Other types of colorectal cancer as of 2017 is still being studied.[rx][rx]

Palliative Care

- Palliative care is recommended for any person who has advanced colon cancer or who has significant symptoms.[rx][rx] Involvement of palliative care may be beneficial to improve the quality of life for both the person and his or her family, by improving symptoms, anxiety and preventing admissions to the hospital.[rx]

- In people with incurable colorectal cancer, palliative care can consist of procedures that relieve symptoms or complications from cancer but do not attempt to cure underlying cancer, thereby improving quality of life. Surgical options may include non-curative surgical removal of some of the cancer tissue, bypassing part of the intestines, or stent placement. These procedures can be considered to improve symptoms and reduce complications such as bleeding from the tumor, abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction.[125] Non-operative methods of symptomatic treatment include radiation therapy to decrease tumor size as well as pain medications.[126]

Surgery for Rectal Cancer

Surgery for rectal cancer is much more complex. High-volume, specialized surgeons and centers have been associated with better outcomes: less likely to need an ostomy bag, lower rates of local recurrence, better overall survival.

-

Mid-to-upper rectal tumors can be resected with a low anterior resection – which leaves the rectal sphincter intact, thereby avoiding a colostomy.

-

Lower-lying tumors – that is, those within 2–3 cm of the anal sphincter or levator muscles, require an abdominal perineal resection and creation of a permanent stoma requiring a colostomy. Surgeon skill often determines how low a low anterior resection can be done.

-

Total mesorectal excision – the meticulous, sharp dissection of perirectal tissues with the removal of the primary tumor and lymph nodes all in one piece, has been shown to decrease local relapse rates.

-

To avoid a stoma – transanal excision of small, early-stage distal tumors with good prognostic features can be considered. (Good is defined here as T1N0, < 3 cm, < 30 percent circumference, not poorly differentiated, and no lymphovascular or perivascular invasion.)

Radiation

- The availability of radiation therapy is most relevant for cancers of the rectum, as local recurrence is much more common than in colon cancer, because of the inability to obtain wide margins and the lack of a serosal barrier. Radiation therapy has improved local control for persons with stages II and III rectal cancer [rx].

- Evidence suggests that compared with postoperative radiation, preoperative radiation is associated with improved surgical outcomes and disease-free survival [rx]. This decision depends on determining the stage of cancer preoperatively, which requires diagnostic services such as magnetic resonance imaging or specialized endorectal ultrasound capability.

- Where these are not available, postoperative delivery of radiation and chemotherapy still provides important benefits. In settings with access to radiation but difficulty obtaining or delivering chemotherapy, or where travel requirements preclude the 5.5 weeks of daily long-course radiotherapy, short-course radiotherapy may be a preferred option [rx].

Chemotherapy

- Evidence-based practice guidelines recommend six months of adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery for persons with stage III colon cancer [rx] and stages II and III rectal cancer. FOLFOX (folinic acid [leucovorin], Fluorouracil, OXaliplatin) is the preferred regimen.

- If chemoradiotherapy is given for rectal cancer, only four months of chemotherapy are required. In addition to the cost of the drugs, however, systemic chemotherapy always requires the ability to monitor blood counts for safety and may require venous access devices.

Management of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

- Metastatic CRC is treated the same way, regardless of whether it started in the colon or rectum. Although the metastatic disease is generally incurable, it is increasingly recognized that, where possible, in 10–20 percent of patients, aggressive resection of liver and lung metastases may lead to cure 20–30 percent of the time.

- Such surgery requires highly specialized training and centers, even in HICs. Alternatives to surgical resection, such as radiofrequency ablation and stereotactic body radiotherapy, can provide long-term control in these situations, but surgical resection is preferred where feasible.

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2001051/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2796096/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4874655/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470380/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5069274/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343633/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65880/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279198/

- https://www.webmd.com/colorectal-cancer/default.htm

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/colon-cance

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bowel-cancer

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/150496.php

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer.html

- https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal

[/bg_collapse]