Causes Symptoms of Backache is a common disorder involving the muscles, nerves, and bones of the back. Pain can vary from a dull constant ache to a sudden sharp feeling. Low back pain may be classified by duration as acute (pain lasting less than 6 weeks), sub-chronic (6 to 12 weeks), or chronic (more than 12 weeks). The condition may be further classified by the underlying cause as either mechanical, non-mechanical, or referred pain. The symptoms of low back pain usually improve within a few weeks from the time they start, with 40-90% of people completely better by six weeks.

Acute low-back pain without sciatica, with some spread of discomfort to the region of the sacroiliac joint, to the outer part of the buttock as well as to the lateral and the back part of the thigh, is a unifying symptom of a very common clinical syndrome whose exact underlying cause remains often uncertain. Most patients fall then into the category of non-specific low-back pain. Probably the pathogenesis is not uniform, and the pain can arise from a variety of structures (muscles, ligament, spine). Pain which persists after 3 to 4 days should warn the clinician that a serious pathological condition may be present which requires a new approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Pain in the lower part of the back is commonly referred to as Lumbago. It can be defined as mild to severe pain or discomfort in the area of the lower back. The pain can be acute (sudden and severe) or chronic if it has lasted more than three months.

Most people will experience lumbago at some point in their life. It is one of the most common reasons people miss work and visit the doctor. It can occur at any age but is a particular problem in younger people whose work involves physical effort and much later in life, in the elderly.

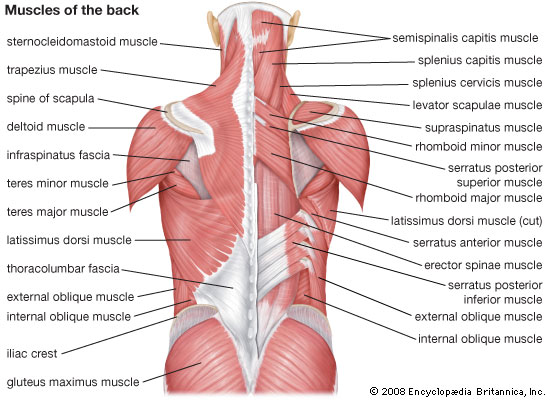

Anatomy of the Low Back / Backache

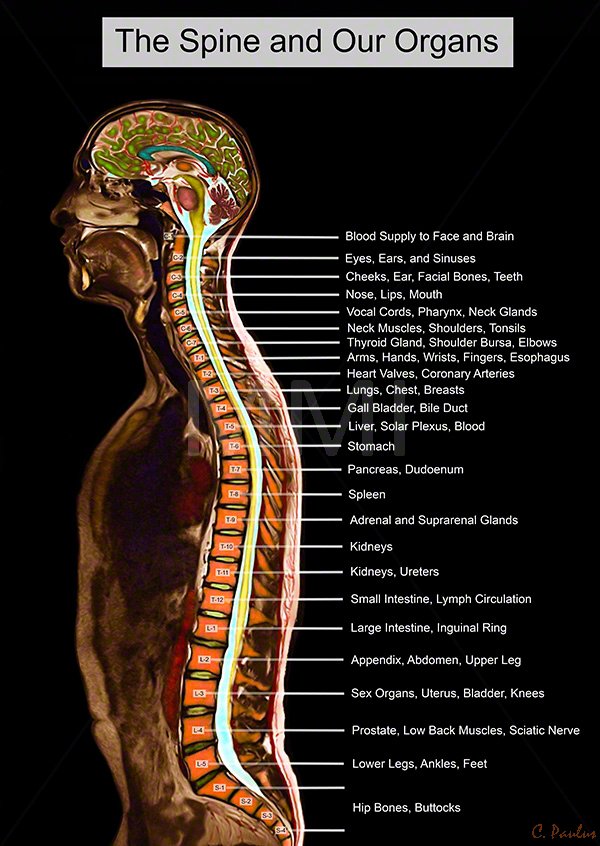

The lumbar spine consists of five vertebrae (L1–L5). The complex anatomy of the lumbar spine is a combination of these strong vertebrae, linked by joint capsules, ligaments, tendons, and muscles, with extensive innervation. The spine is designed to be strong, since it has to protect the spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. At the same time, it is highly flexible, providing for mobility in many different planes.

The mobility of the vertebral column is provided by the symphyseal joints between the vertebral bodies, with an IVD in between. The facet joints are located between and behind adjacent vertebrae, contributing to spine stability. They are found at every spinal level and provide about 20% of the torsional (twisting) stability in the neck and low back segments [rx]. Ligaments aid in joint stability during rest and movement, preventing injury from hyperextension and hyperflexion. The three main ligaments are the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), and ligamentum flavum (LF). The canal is bordered by vertebral bodies and discs anteriorly and by laminae and LF posteriorly. Both the ALL and PLL run the entire length of the spine, anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively. Laterally, spinal nerves and vessels come out from the intervertebral foramen. Beneath each lumbar vertebra, there is the corresponding foramen, from which spinal nerve roots exit. For example, the L1 neural foramina are located just below the L1 vertebra, from where the L1 nerve root exits.

IVDs are located between vertebrae. They are compressible structures able to distribute compressive loads through osmotic pressurization. In the IVD, the annulus fibrosus (AF), a concentric ring structure of organized lamellar collagen, surrounds the proteoglycan-rich inner nucleus pulposus (NP). Discs are avascular in adulthood, except for the periphery. At birth, the human disc has some vascular supply but these vessels soon recede, leaving the disc with little direct blood supply in the healthy adult [rx]. Hence, metabolic support of much of the IVD is dependent on the cartilaginous endplates adjacent to the vertebral body. A meningeal branch of the spinal nerve, better known as the recurrent sinuvertebral nerve, innervates the area around the disc space [rx].

The lumbar spine is governed by four functional groups of muscles, split into extensors, flexors, lateral flexors, and rotators. The lumbar vertebrae are vascularized by lumbar arteries that originate in the aorta. Spinal branches of the lumbar arteries enter the intervertebral foramen at each level, dividing themselves into smaller anterior and posterior branches [rx]. The venous drainage parallels the arterial supply [rx].

Typically, the end of the spinal cord forms the conus medullaris within the lumbar spinal canal at the lower margin of the L2 vertebra [rx]. All lumbar spinal nerve roots stem from the connection between the dorsal or posterior (somatic sensory) root from the posterolateral aspect of the spinal cord and the ventral or anterior (somatic motor) root from the anterolateral aspect of the cord [rx. The roots then flow down through the spinal canal, developing into the cauda equina, before exiting as a single pair of spinal nerves at their respective intervertebral foramina. Cell bodies of the motor nerve fibers can be found in the ventral or anterior horns of the spinal cord, whereas those of the sensory nerve fibers are in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) at each level. One or more recurrent meningeal branches, known as the sinuvertebral nerves, run out from the lumbar spinal nerves. The sinuvertebral nerve, or Luschka’s nerve, is a recurrent branch created from the merging of the grey ramus communicans (GRC) with a small branch coming from the proximal end of the anterior primary ramus of the spinal nerve. This polisegmentary mixed nerve directly re-enters the spinal canal and gives off ascending and descending anastomosing branches comprising both somatic and autonomic fibers for the posterolateral annulus, the posterior vertebral body and the periosteum, and the ventral meninges [rx], [rx]. The sinuvertebral nerves connect with branches from radicular levels both above and below the point of entry, in addition to the contralateral side, meaning that localizing pain from involvement of these nerves is challenging [rx]. Also, the facet joints receive two-level innervation comprising somatic and autonomic components. The former convey a well-defined local pain, while the autonomic afferents transmit referred pain.

Causes of Lumbago /Backache

The human back is composed of a complex structure of muscles, ligaments, tendons, disks and bones – the segments of our spine are cushioned with cartilage-like pads called disks. Problems with any of these components can lead to back pain. In some cases of back pain, its cause is never found.

Problems with the spine such as osteoporosis can lead to back pain.

Strain – the most common causes of back pain are:

- Strained muscles

- Strained ligaments

- A muscle spasm

Things that can lead to strains or spasms include:

- Lifting something improperly

- Lifting something that is too heavy

- The result of an abrupt and awkward movement

Structural problems –

- Sprains and strains – account for most acute back pain. Sprains are caused by overstretching or tearing ligaments, and strains are tears in tendon or muscle. Both can occur from twisting or lifting something improperly, lifting something too heavy, or overstretching. Such movements may also trigger spasms in back muscles, which can also be painful.

- Intervertebral disc degeneration – is one of the most common mechanical causes of low back pain, and it occurs when the usually rubbery discs lose integrity as a normal process of aging. In a healthy back, intervertebral discs provide height and allow bending, flexion, and torsion of the lower back. As the discs deteriorate, they lose their cushioning ability.

- Herniated or ruptured discs – can occur when the intervertebral discs become compressed and bulge outward (herniation) or rupture, causing low back pain.

- Radiculopathy – is a condition caused by compression, inflammation and/or injury to a spinal nerve root. Pressure on the nerve root results in pain, numbness, or a tingling sensation that travels or radiates to other areas of the body that are served by that nerve. Radiculopathy may occur when spinal stenosis or a herniated or ruptured disc compresses the nerve root.

- Sciatica – is a form of radiculopathy caused by compression of the sciatic nerve, the large nerve that travels through the buttocks and extends down the back of the leg. This compression causes shock-like or burning low back pain combined with pain through the buttocks and down one leg, occasionally reaching the foot. In the most extreme cases, when the nerve is pinched between the disc and the adjacent bone, the symptoms may involve not only pain, but numbness and muscle weakness in the leg because of interrupted nerve signaling. The condition may also be caused by a tumor or cyst that presses on the sciatic nerve or its roots.

- Spondylolisthesis – is a condition in which a vertebra of the lower spine slips out of place, pinching the nerves exiting the spinal column.

- A traumatic injury – such as from playing sports, car accidents, or a fall can injure tendons, ligaments or muscle resulting in low back pain. Traumatic injury may also cause the spine to become overly compressed, which in turn can cause an intervertebral disc to rupture or herniate, exerting pressure on any of the nerves rooted to the spinal cord. When spinal nerves become compressed and irritated, back pain and sciatica may result.

- Ruptured disks – each vertebra in our spine is cushioned by disks. If the disk ruptures there will be more pressure on a nerve, resulting in back pain.

- Bulging disks – in much the same way as ruptured disks, a bulging disk can result in more pressure on a nerve.

- Sciatica – a sharp and shooting pain that travels through the buttock and down the back of the leg, caused by a bulging or herniated disk pressing on a nerve.

- Arthritis – patients with osteoarthritis commonly experience problems with the joints in the hips, lower back, knees and hands. In some cases, spinal stenosis can develop, which is the term used to describe when the space around the spinal cord narrows.

- Abnormal curvature of the spine – if the spine curves in an unusual way the patient is more likely to experience back pain. An example is scoliosis, a condition in which the spine curves to the side.

- Osteoporosis – bones, including the vertebrae of the spine, become brittle and porous, making compression fractures more likely.

- Spinal stenosis – is a narrowing of the spinal column that puts pressure on the spinal cord and nerves that can cause pain or numbness with walking and over time leads to leg weakness and sensory loss.

- Skeletal irregularities – include scoliosis, a curvature of the spine that does not usually cause pain until middle age; lordosis, an abnormally accentuated arch in the lower back; and other congenital anomalies of the spine.

- Abdominal aortic aneurysms – occur when the large blood vessel that supplies blood to the abdomen, pelvis, and legs becomes abnormally enlarged. Back pain can be a sign that an aneurysm is becoming larger and that the risk of rupture should be assessed.

- Kidney stones – can cause sharp pain in the lower back, usually on one side.

Below are some other causes of back pain

- Cauda equina syndrome – the cauda equine is a bundle of spinal nerve roots that arise from the lower end of the spinal cord. People with cauda equine syndrome feel a dull pain in the lower back and upper buttocks, as well as analgesia (lack of feeling) in the buttocks, genitalia, and thigh. There are sometimes bowel and bladder function disturbances.

- Cancer of the spine – a tumor located on the spine may press against a nerve, resulting in back pain.

- Infection of the spine – if the patient has an elevated body temperature (fever) as well as a tender warm area on the back, it could be caused by an infection of the spine.

- Other infections – pelvic inflammatory disease (females), bladder, or kidney infections may also lead to back pain.

- Endometriosis – is the buildup of uterine tissue in places outside the uterus.

- Fibromyalgia – a chronic pain syndrome involving widespread muscle pain and fatigue.

- Sleep disorders – individuals with sleep disorders are more likely to experience back pain, compared to others.

- Shingles – an infection that can affect the nerves may lead to back pain, depending on the nerves affected.

- Bad mattress – if a mattress does not support specific parts of the body and keep the spine straight, there is a greater risk of developing back pain.

Everyday activities or poor posture

Back pain can also be the result of some everyday activity or poor posture. Examples include:

Adopting a very hunched sitting position when using computers can result in increased back and shoulder problems over time.

- Bending awkwardly

- Pushing something

- Pulling something

- Carrying something

- Lifting something

- Standing for long periods

- Bending down for long periods

- Twisting

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Muscle tension

- Over-stretching

- Straining the neck forward, such as when driving or using a computer

- Long driving sessions without a break, even when not hunched

- Exertion or lifting.

- Severe blow or fall.

- Back disorders.

- Infections.

- Ruptured lumbar disk.

- Nerve dysfunction.

- Osteoporosis.

- Spondylosis (hardening and stiffening of the spinal column).

- Congenital problem.

- Childbirth.

- Often there is no obvious cause.

Jobs That Can Cause Lower Back Pain

- Airline crew (pilots, baggage handlers)

- Surgeons

- Nurses & healthcare workers

- Bus and cab drivers

- Warehouse workers

- Construction workers

- Carpet installers and cleaners

- Farmers (agricultural, dairy)

- Firefighters and police

- Janitors

- Mechanics

- Office personnel (eg, telemarketers, file clerks, computer operators)

The symptom of Lumbago /Backache

The main symptom of back pain is, as the name suggests, an ache or pain anywhere on

- Pain in the back, and sometimes all the way down to the buttocks and legs. Some back issuescan cause pain in other parts of the body, depending on the nerves affected.

- In most cases, signs, and symptoms clear up on their own within a short period.If any of the following signs or symptoms accompany a back pain, people should see their doctor:

- Pain. It may be continuous, or only occur when you are in a certain position. The pain may be aggravated by coughing or sneezing, bending or twisting.

- Patients who have been taking steroids for a few months

- Drug abusers

- Patients with cancer

- Patients who have had cancer

- Patients with depressed immune systems

- Stiffness.

According to the British National Health Service (NHS), the following groups of people should seek medical advice if they experience back pain:

- Weight loss

- Elevated body temperature (fever)

- Inflammation (swelling) on the back

- Persistent back pain – lying down or resting does not help

- Pain down the legs

- Pain reaches below the knees

- A recent injury, blow or trauma to your back

- Urinary incontinence – you pee unintentionally (even small amounts)

- Difficulty urinating – passing urine is hard

- Fecal incontinence – you lose your bowel control (you poo unintentionally)

- Numbness around the genitals

- Numbness around the anus

- Numbness around the buttocks

- dull ache,

- numbness,

- tingling,

- sharp pain,

- pulsating pain,

- pain with movement of the spine,

- pins and needles sensation,

- muscle spasm,

- tenderness,

- sciatica with shooting pain down one or both lower extremities

- People aged less than 20 and more than 55 years

- Additionally, people who experience pain symptoms after a major trauma (such as a car accident) are advised to see a doctor. If low back pain interferes with daily activities, mobility, sleep, or if there are other troubling symptoms, medical attention should be sought.

Risk increases with

- Biomechanical risk factors.

- Sedentary occupations.

- Gardening and other yard work.

- Sports and exercise participation, especially if infrequent.

- Obesity.

Preventive measures

- Exercises to strengthen lower back muscles.

- Learn how to lift heavy objects.

- Sit properly.

- Back support in bed.

- Lose weight, if obese.

- Choose proper footwear.

- Wear special back support devices.

Red flag conditions indicating possible underlying spinal pathology or nerve root problemsw9

Red flags

-

Onset age < 20 or > 55 years

-

Non-mechanical pain (unrelated to time or activity)

-

Thoracic pain

-

Previous history of carcinoma, steroids, HIV

-

Feeling unwell

-

Weight loss

-

Widespread neurological symptoms

-

Structural spinal deformity

Indicators for nerve root problems

-

Unilateral leg pain > low back pain

-

Radiates to foot or toes

-

Numbness and paraesthesia in the same distribution

-

Straight leg raising test induces more leg pain

-

Localized neurology (limited to one nerve root)

Diagnosis of Lumbago /Backache

Suspected disk, nerve, tendon, and other problems – X-rays or some other imaging scan, such as a CT (computerized tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan may be used to get a better view of the state of the soft tissues in the patient’s back.

- Blood tests – CBC ,ESR,Hb, RBS,CRP, Serum Creatinine,Serum Electrolyte,

- Myelograms

- Discography.

- Electrodiagnostics

- Bone scans

- Ultrasound imaging

- X-rays – can show the alignment of the bones and whether the patient has arthritis or broken bones. They are not ideal for detecting problems with muscles, the spinal cord, nerves or disks.

- MRI or CT scans – these are good for revealing herniated disks or problems with tissue, tendons, nerves, ligaments, blood vessels, muscles and bones.

- Bone scan – a bone scan may be used for detecting bone tumors or compression fractures caused by brittle bones (osteoporosis). The patient receives an injection of a tracer (a radioactive substance) into a vein. The tracer collects in the bones and helps the doctor detect bone problems with the aid of a special camera.

- Electromyography or EMG – the electrical impulses produced by nerves in response to muscles is measured. This study can confirm nerve compression which may occur with a herniated disk or spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal).

[stextbox id=’info’]

| Syndrome | Findings | Assessment/Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Facet syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings (not indicated on intial evaluation):

|

Differential diagnosis:

Treatment: |

| Sacro-iliac joint syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings (not indicated on intial evaluation):

|

Functional disturbance: muscular imbalance Treatment: stabilizing exercises, analgesics (1–3 days) if needed, manual medicine, sacro-iliac joint injection if indicated |

| Myofascial pain syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological and histological findings:

|

Local treatment: |

| Functional instability | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings:

|

|

Treatments for acute and chronic low back painRx

| Effectiveness | Acute low back pain | Chronic low back pain |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Advice to stay active, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Exercise therapy, Intensive multidisciplinary treatment programmes |

| Trade off | Muscle relaxants | Muscle relaxants |

| Likely to be beneficial | Spinal manipulation, behaviour therapy, multidisciplinary treatment programmes (for subacute low back pain) | Analgesics, acupuncture, antidepressants, back schools, behaviour therapy, NSAIDs, spinal manipulation |

| Unknown | Analgesics, acupuncture, back schools, epidural steroid injections, lumbar supports, massage, multidisciplinary treatment (for acute low back pain), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, traction, temperature treatments, electromyographical biofeedback | Epidural steroid injections, EMG biofeedback, lumbar supports, massage, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, traction, local injections |

| Unlikely to be beneficial | Specific back exercises | — |

| Ineffective or harmful | Bed rest | Facet joint injections |

[/stextbox]

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4926733/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1479671/

- http://www.backpaineurope.org/

- https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/evidence-information/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2138352

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4857557/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Low_back_pain

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lumbago

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002961034901793

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003277814000380

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0034709412701836

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/low-back

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/10/131017080104.htm

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171129090431.htm

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171129090431.htm

- https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Low-Back-Pain-Fact-Sheet

- https://nccih.nih.gov/health/pain/spinemanipulation.htm

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Low_Back_Pain.html?id=ualzJ7SXVWYC

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Acute_Lumbago.html?id=XbowAAAAIAAJ

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Sciatic_Lumbago_and_Brachialga.html?id=d9NfGwAACAAJ

- https://medlineplus.gov/backpain.html

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/art.34347

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00420-002-0332-6

- https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00420-002-0332-6.pdf

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00435945

- https://www.webmd.com/back-pain/back-pain-treatment

- https://www.healthline.com/health/back-pain

- https://www.netdoctor.co.uk/conditions/aches-and-pains/a2845/low-back-pain-lumbago/

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322123.php

[/bg_collapse]