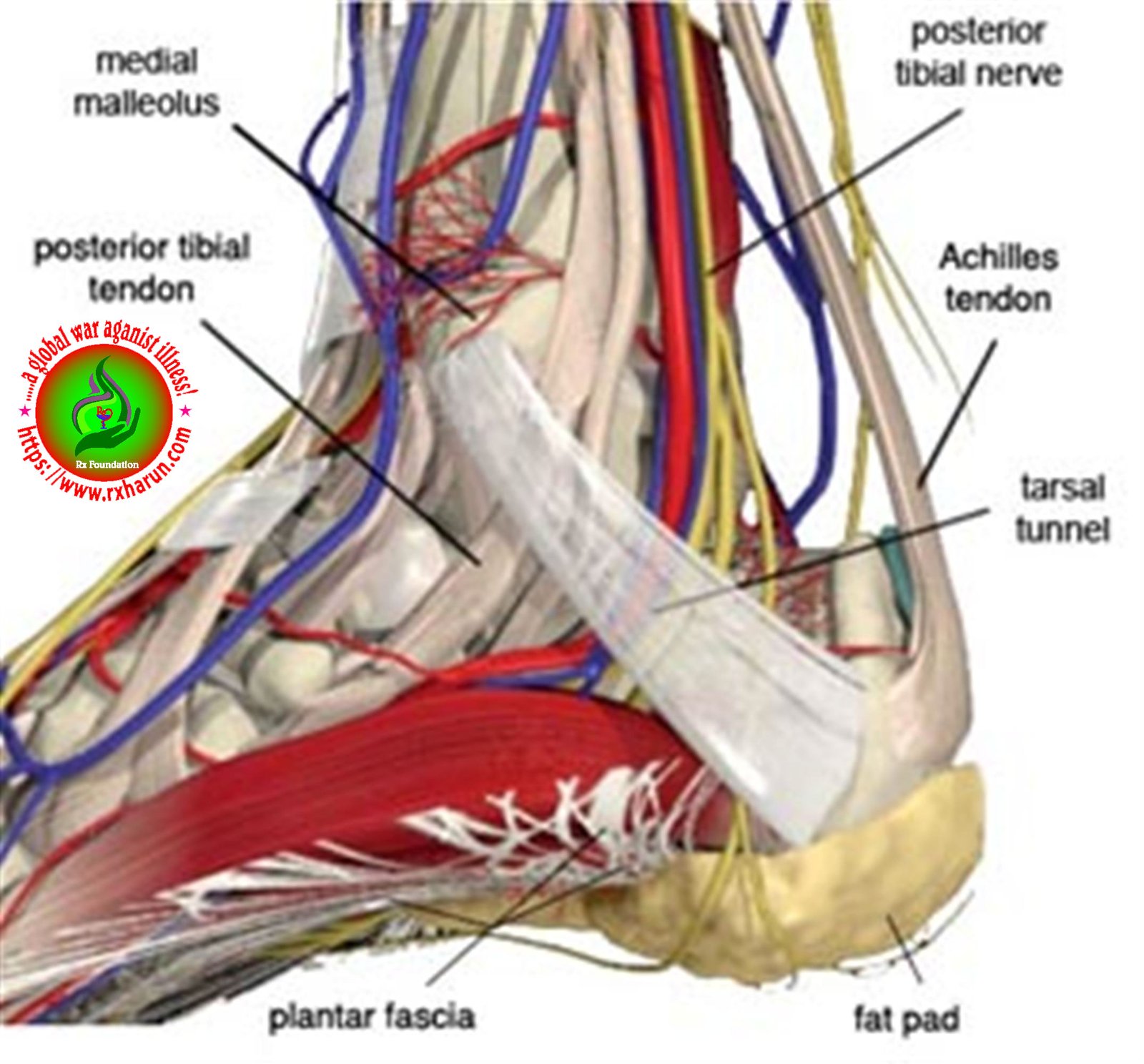

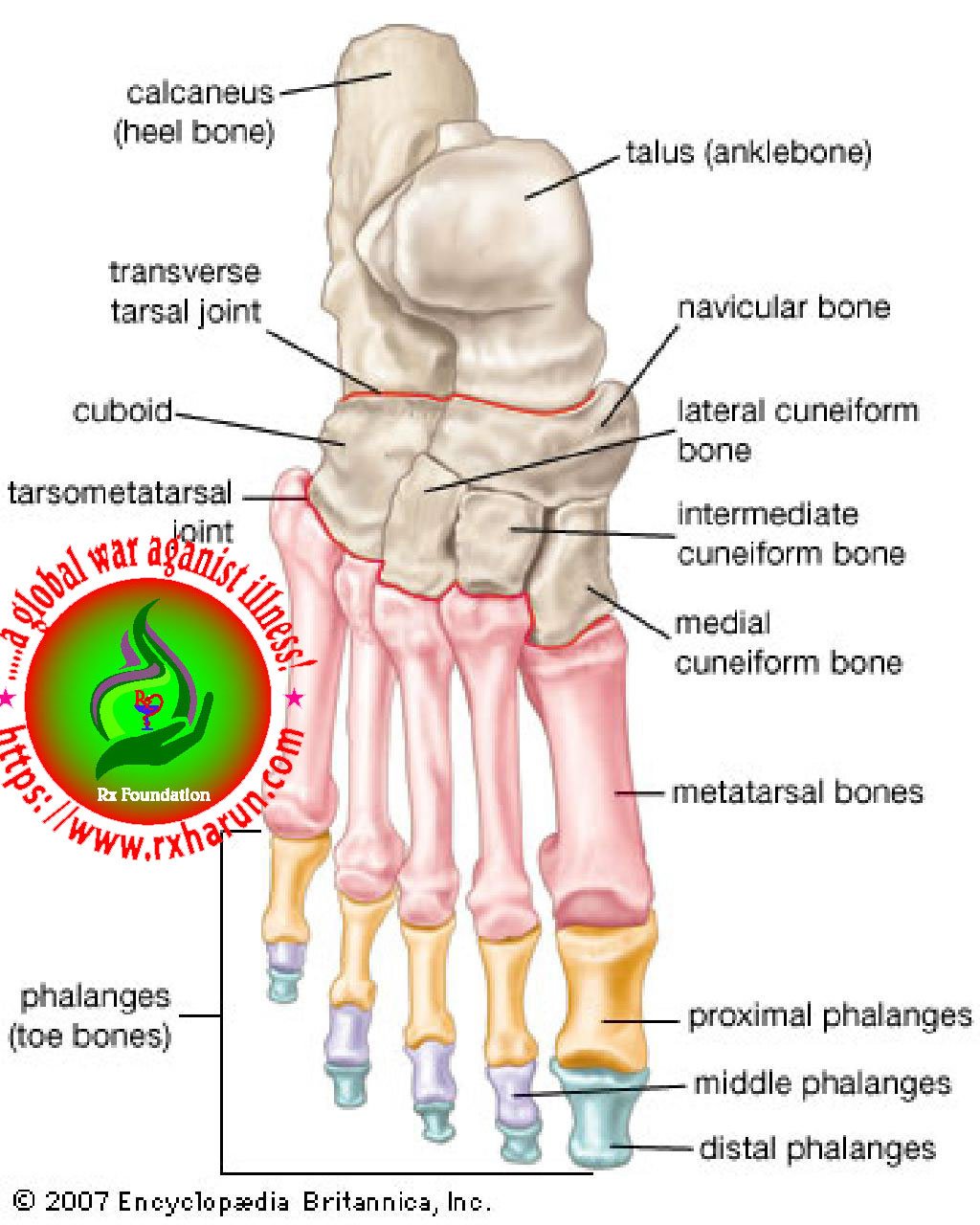

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) also known as posterior tibial neuralgia, is a compression neuropathy and painful foot condition in which the tibial nerve is compressed as it travels through the tarsal tunnel. This tunnel is found along the inner leg behind the medial malleolus (bump on the inside of the ankle). The posterior tibial artery, tibial nerve, and tendons of the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles travel in a bundle through the tarsal tunnel. Inside the tunnel, the nerve splits into three different segments. One nerve (calcaneal) continues to the heel, the other two (medial and lateral plantar nerves) continue on to the bottom of the foot.

Anatomy of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Posterior tarsal tunnel

- an anatomic structure defined by

- the flexor retinaculum (laciniate ligament)

- calcaneus (medial)

- talus (medial)

- abductor hallucis (inferior)

Contents include

- tibial nerve

- posterior tibial artery

- FHL tendon

- FDL tendon

- tibialis posterior tendon

Tibial nerve

Has 3 distal branches

- medial plantar

- lateral plantar

- medial calcaneal

- the medial and lateral plantar nerves can be compressed in their own sheath distal to tarsal tunnel

- bifurcation of nerves occurs proximal to tarsal tunnel in 5% of cases

Anterior tarsal tunnel

Flattened space defined by

- inferior extensor retinaculum

- fascia overlying the talus and navicular

Contents include

- deep peroneal nerve and branches

- EHL

- EDL

- dorsalis pedis artery

Types of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Types of impingement

Intrinsic

- ganglion cyst

- tendinopathy

- tenosynovitis

- lipoma/tumor

- peri-neural fibrosis

- osteophytes

Extrinsic

- shoes

- trauma

- anatomic deformity (tarsal coalition, valgus hindfoot)

- post-surgical scaring

- systemic inflammatory disease

- edema of the lower extremity

- cause of impingement able to be identified in 80% of cases

Causes of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is divided into intrinsic and extrinsic etiologies.[rx][rx]

-

Extrinsic causes include poorly fitting shoes, trauma, anatomic-biomechanical abnormalities (tarsal coalition, valgus or varus hindfoot), post-surgical scarring, systemic diseases, generalized lower extremity edema, systemic inflammatory arthropathies, diabetes, and post-surgical scarring.

-

Intrinsic causes include tendinopathy, tenosynovitis, perineural fibrosis, osteophytes, hypertrophic retinaculum, and space-occupying or mass effect lesions (enlarged or varicose veins, ganglion cyst, lipoma, neoplasm, and neuroma). Arterial insufficiency can lead to nerve ischemia.

severely flat feet, because flattened feet can stretch the tibial nerve

- Pronation – Rolling your feet inward when walking or running, which can later cause flat feet.

- Swelling of the flexor tendons – These tendons, which run down the inside of the ankle and under the foot to the toes, allow you to move your toes.

- Inflamed joints cause pressure and swelling, and thus can negatively affect the tibial nerve.

- Venous stasis edema/swelling – This malfunction of the venous circulatory system causes blood to back up and pool in the tissue, thus inflicting pressure on the tibial nerve.

- benign bony growths in the tarsal tunnel

- varicose veins in the membrane surrounding the tibial nerve, which cause compression on the nerve

- inflammation from arthritis

- lesions and masses like tumors or lipomas near the tibial nerve

- injuries or trauma, like an ankle sprain or fracture — inflammation and swelling from which lead to tarsal tunnel syndrome

- diabetes, which makes the nerve more vulnerable to compression

- Having flat feet or fallen arches, which can produce strain or compression on the tibial nerve

- Swelling caused by an ankle sprain which then compresses on the nerve

- Diseases such as arthritis or diabetes which can cause swelling, thus resulting in nerve compression

- An enlarged or abnormal structure, such as a varicose vein, ganglion cyst, swollen tendon, or bone spur, that might compress the nerve

- Osteoarthritis at the ankle joint – possibly as a result of an old injury

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Diabetes

- Overpronation

- Tenosynovitis

- Talonavicular coalition – fusing of two of the tarsal bones.

- A cyst or ganglion in the tarsal tunnel.

Symptoms of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Some of the symptoms are

- Pain and tingling in and around ankles and sometimes the toes

- Swelling of the feet and ankle area.

- Painful burning, tingling, or numb sensations in the lower legs. Pain worsens and spreads after standing for long periods; pain is worse with activity and is relieved by rest.

- Electric shock sensations

- Pain radiating up into the leg, behind the shin, and down into the arch, heel, and toes

- Hot and cold sensations in the feet

- A feeling as though the feet do not have enough padding

- Pain while operating automobiles

- Pain along the Posterior Tibial nerve path

- Burning sensation on the bottom of the foot that radiates upward reaching the knee

- “Pins and needles”-type feeling and increased sensation on the feet

- A positive Tinel’s sign

Tinel’s sign is a tingling electric shock sensation that occurs when you tap over an affected nerve. The sensation usually travels into the foot but can also travel up the inner leg as well.

Diagnosis of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

The physical therapist should inquire about the following

- Mechanism of injury (MOI) – was there any trauma, strain, or overuse?

- Duration and location of pain and parathesia?

- Weakness or difficulty walking?

- Back or buttock pain associated with more distal symptoms?

- Pain getting worse, staying the same, or getting better?

Key history Findings

- Parathesia or burning sensation in the territory of the distal branches of the tibial nerve

- Prolonged walking or standing often exacerbates patient’s pain

- Dysesthesia (an abnormal and unpleasant sensation) arises during the night and can disturb sleep

- Weakness of muscles

Observation

- Muscle atrophy of the abductor hallucis muscle may be seen

- Check for arch stability

- Position of the talus and calcaneous

Gait Analysis

- Assess for abnormalities (excessive pronation/supination, toe out, excessive inversion/eversion, antalgic gait, etc.)

Sensory Testing

- Test light touch, 2-point discrimination, and pinprick in the lower extremity

- Deficits will be in the distribution of the posterior tibial nerve

Palpation

- Tender to palpation in between the medial malleolus and Achilles tendon

- Painful in 60-100% of those affected

Range of Motion (ROM)

- Focus on ankle and toe ROM

Manual Muscle Testing (MMT)

- Decreased strength generally occurs late in the progression of TTS

- The phalangeal abductors are impacted first followed by the short-phalangeal flexors

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Severity Rating Scale

A score of 10 indicates a normal foot and 0 indicates the most symptomatic foot.

Scoring for each symptom

-

2 points for the absence of features

-

1 point for some features

-

0 points for definite features

The five symptoms

-

Spontaneous pain or pain with movement,

-

Burning pain

-

Tinel sign

-

Sensory disturbance

-

Muscle atrophy or weakness

Special Tests

Tinel’s Sign

Dorsiflexion-Eversion Test

- Percussion of the tarsal tunnel results in distal radiation of paresthesias

- Elicited in over 50% of those affected

Dorsiflexion – Eversion Test

- Place the patient’s foot into full dorsiflexion and eversion and hold for 5-10 seconds

- The results are that it elicits the patient’s symptoms

EMG studies

- The presence of an isolated tibial nerve lesion in the tarsal tunnel is confirmed by measurement of the sensory and motor nerve conduction velocity (NCV).

- Sensory conduction velocity of the medial and lateral plantar nerves. This is best done by recording from the tibial nerve just above the flexor retinaculum and stimulating the nerves at the vault of the foot. When surface electrodes are used, the responses to stimulation are of low amplitude.

- Measurement of the motor NCV through the recording of the distal motor latency at the abductor hallucis brevis muscle is a much easier, but less sensitive method. The important finding on electromyography (EMG) is the demonstration of axonal injury when the EMG is recorded from the distal muscles supplied by the tibial nerve.

Imaging Tests of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

- X-rays – X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays to rule out a broken bone in your ankle or foot. A broken bone can cause similar symptoms of pain and swelling.

- Stress x-rays – In addition to plain x-rays, your doctor may also order stress x-rays. These scans are taken while the ankle is being pushed in different directions. Stress x-rays help to show whether the ankle is moving abnormally because of injured ligaments.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan – Your doctor may order an MRI if he or she suspects a very severe injury to the ligaments, damage to the cartilage or bone of the joint surface, a small bone chip, or another problem. The MRI may not be ordered until after the period of swelling and bruising resolves.

- Ultrasound – This imaging scan allows your doctor to observe the ligament directly while he or she moves your ankle. This helps your doctor to determine how much stability the ligament

Treatments of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Nonsurgical Treatment

Many treatment options, often used in combination, are available to treat tarsal tunnel syndrome. These include

- Rest – The easiest and most immediate way to reduce inflammation anywhere in the body is to stop using and putting pressure on the affected area. How long an individual should rest the foot depends mostly on the severity of symptoms. For minor cases, rest may mean replacing running with swimming. For more severe cases, resting the nerve may require completely refraining from exercise and activity.

- Ice – An ice pack covered with a cloth or towel can be applied to the inside of the ankle and foot for 20-minute sessions to reduce inflammation. It is best to have the foot elevated during this time. Icing sessions can be repeated several times daily, as long as breaks of at least 40 minutes are taken.

- Oral medications – Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, help reduce the pain and inflammation.

- Immobilization – Restricting movement of the foot by wearing a cast is sometimes necessary to enable the nerve and surrounding tissue to heal.

- Injection therapy – Injections of a local anesthetic provide pain relief, and an injected corticosteroid may be useful in treating the inflammation.

- Orthotic devices – Custom shoe inserts may be prescribed to help maintain the arch and limit excessive motion that can cause compression of the nerve.

- Shoes – Supportive shoes may be recommended.

- Compression and elevation – Compressing the foot, and keeping it raised above the heart, helps reduce blood flow to the foot, and so reduces inflammation. Try wrapping the foot with an ACE wrap, and resting it on a pillow while sitting and sleeping.

- Over-the-counter pain and anti-inflammatory medications – These can include ibuprofen and acetaminophen.

- Full immobilization – For severe cases, especially those involving physical damage to the nerve, a cast may be necessary to restrict movement completely, allowing the nerve, joint, and surrounding tissues a chance to heal.

- Injection therapy – For very painful or disabling symptoms, anti-inflammatory medication, such as corticosteroids and local anesthetics, may be directly injected into the nerve.

- Orthopedic devices and corrective shoes – Podiatrists can make specialized shoes, and inserts that help support the arch and limit motions that can further irritate the inflamed nerve and surrounding tissues. Shoes also exist to help prevent pronation or inward rolling of the foot.

- Reducing foot pressure – In some cases, wearing looser or larger fitting footwear and socks may help reduce tightness around the foot.

- Physical therapy – Physical therapy exercises can often help reduce symptoms of TTS long-term, by slowing stretching and strengthening the connective tissues, mobilizing the tibial nerve and opening the surrounding joint space to reduce compression.

- Bracing – Patients with flatfoot or those with severe symptoms and nerve damage may be fitted with a brace to reduce the amount of pressure on the foot.

Post Operative Treatment

| Timeframe | Goals | Intervention | |

| Phase I | 1-3 wks | -Protectthe nerve, joint, and incision site -Control swelling -Reduce pn |

-Immobilization with NWB precautions -Ankle passive ROM -RICE -Gait training with AD |

| Phase II | 3-6 wks | -Prevent contractures -Prevent scar tissue adhesions -Increase joint mobility |

-WBAT -Gentle passive and active ankle stretching -Begin tibial nerve glide with anti-tension technique (foot PF and inverted) -Gait training to tolerance with protective splint -Aquatic therapy |

| Phase III | 6-12 wks | -Normal gait mechanics -Increase ankle mobility -Increase PF strength -Specific skill development |

-Gait training without splint -Pain free theraband exercises -Tibial nerve glide progression (foot everted and dorsiflexed) -Weight bearing exercises -Resistive exercises (impairment approach) -Balance/proprioceptive training -Specific skill development in pain free range -Cardiovascular fitness |

Exercises

As symptoms become less painful or easily irritated, strengthening exercises should be done to help prevent problems, including pronation or rolling of the foot, which can worsen symptoms.

Common exercises recommended for the treatment of TTS include

Ankle pumps, circles, and eversion or inversion

A person can gently stretch the ankle by bending the foot towards the ground with the legs extended.

- Sitting down with the legs extended, slowly and gently bend the foot at the ankles downward towards the ground, and then upwards towards the body, as much as possible, without pain. Repeat several times.

- Slowly and gently roll the ankles through their circular range of motion as aggressively, as is comfortable, several times.

- Slowly turn the ankles inward and outward, creating a windshield wiper motion, several times, as far as is comfortable.

- Repeat all three exercises several times daily.

Heel-toe raises

- Standing straight, slowly raise or flex the toes upward, as far as possible, without pain.

- Slowly lower the toes and gently raise the heels, putting gradual pressure on the ball of the foot.

- Repeat this exercise 10 times and perform several times daily.

Pencil toe lifts

- Sitting down with the legs fully extended, place a pencil or pen on the floor directly below the toes and attempt to pick it up using only the toes.

- Once the pencil is fully grasped, hold for 10 to 15 seconds.

- Relax the toes.

- Repeat 10 times and perform several times daily.

Balance exercises

- Standing straight slowly raise one leg and rest the sole of the raised foot on the inner calf of the other foot.

- Hold for at least 10 to 15 seconds or, as long as is comfortable, without overstretching the inner ankle and foot. If too wobbly, stop by lowering the foot and restarting the exercise.

- For a more intense version of this exercise, gradually lift the raised leg further in the air, away from the body.

Plantar fascia stretch

- Sitting down with the legs extended, as far as comfortable, reach out and grasp the big toe and top of the sole, then gently pull backward. This can also be done using a stretching band, dishtowel, or sock.

- Stretch the foot backward until a stretch that runs from the sole to the ball of the foot is felt.

- Hold for 30 seconds before slowly releasing the foot.

- Repeat the stretch at least three to five times, three times daily for several weeks, even after initial symptoms have greatly improved to reduce the chances of them returning.

- The plantar fascia ligament can also be stretched by rolling out the arch, sole, and heel in a gentle downward motion on something round, such as a soup can, therapy ball, tennis ball, or rolling pin.

Gastrocnemius stretch

- Standing a small distance away from a wall, step one foot forward, closer to the wall, and lean in, pressing the hands into the wall while keeping the back leg straight. This position should look somewhat similar to an assisted lunge.

- Widen or deepen, the stretch as feels comfortable or produces a notice, pain-free stretch along the full-length of the back of the calf.

- Start by holding the stretch for 10 to 15 seconds, gradually increasing holding time to reach 45-second intervals.

- Repeat the stretch three to five times consecutively, three times daily for several weeks.

- For a more intense stretch, try standing on a step with the foot halfway hanging off the edge, and then gently push the heel downwards. Hold for as long as feels comfortable, up to 10 times daily.

Soleus muscle stretch

- Repeat the steps of the gastrocnemius stretch, except with the back leg being stretched bent at the knee.

- To increase the stretch, place something under the front or ball of the foot, or prop the ball of the foot up on the wall.

Risk factors

Jobs that require standing for long hours, such as serving or retail jobs, may increase the risk of TTS.

Though anyone can develop TTS at any age, some factors greatly increase the risk of developing the condition.

Common risk factors for TTS include

- chronic overpronation or rolling inward of the foot when walking

- flat feet or fallen arches

- rheumatoid arthritis

- osteoarthritis

- diabetes and other metabolic conditions

- ankle or foot injury

- jobs that require standing or walking for a long time, such as retail, teaching, mechanical, manufacturing, and surgical jobs

- poorly-fitting shoes that allow the foot to pronate inward or do not support the arch and ankle

- nerve disease

- cysts, tumors, or small masses in the foot and ankle area

- proliferative synovitis or inflammation of the synovial membrane

- varicose veins or inflamed, enlarged veins

- foot deformities

- reflex sympathetic dystrophy

- peripheral neuropathy conditions

- generalized leg edema or swelling, especially related to pregnancy

- being overweight

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21600447

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9498577

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513273/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2210534

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16958391

[/bg_collapse]

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars