The skin is the soft outer covering of vertebrates that guards the underlying muscles, bones, ligaments, and internal organs. Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different developmental origin, structure and chemical compositions. The adjective cutaneous means “of the skin” (from Latin cutis ‘skin’). In mammals, the skin is an organ of the integumentary system made up of multiple layers of ectodermal tissue, and guards the underlying muscles, bones, ligaments and internal organs. Skin of a different nature exists in amphibians, reptiles, and birds.[2] Skin (including cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues) plays crucial roles in formation, structure and function of extra-skeletal apparatus such as horns of bovids [e.g. cattle] and rhinos, cervids’ antlers, giraffids’ ossicones, armadillos’ osteoderm, and os penis/ os clitoris.[rx]

Key Points

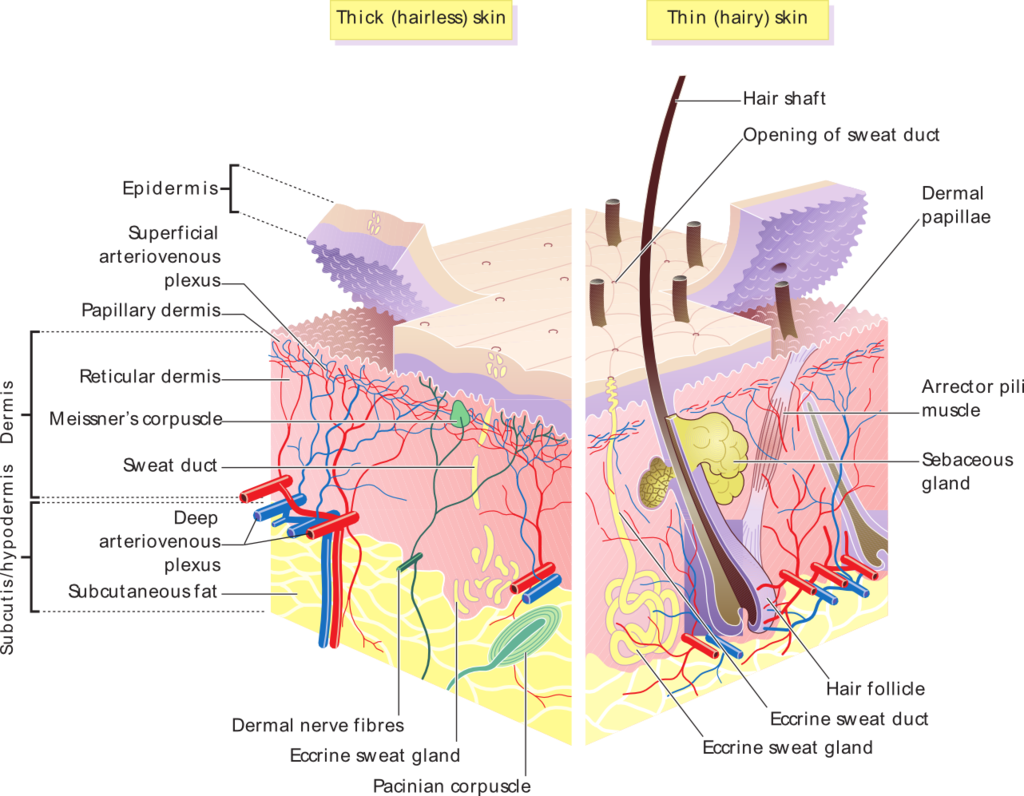

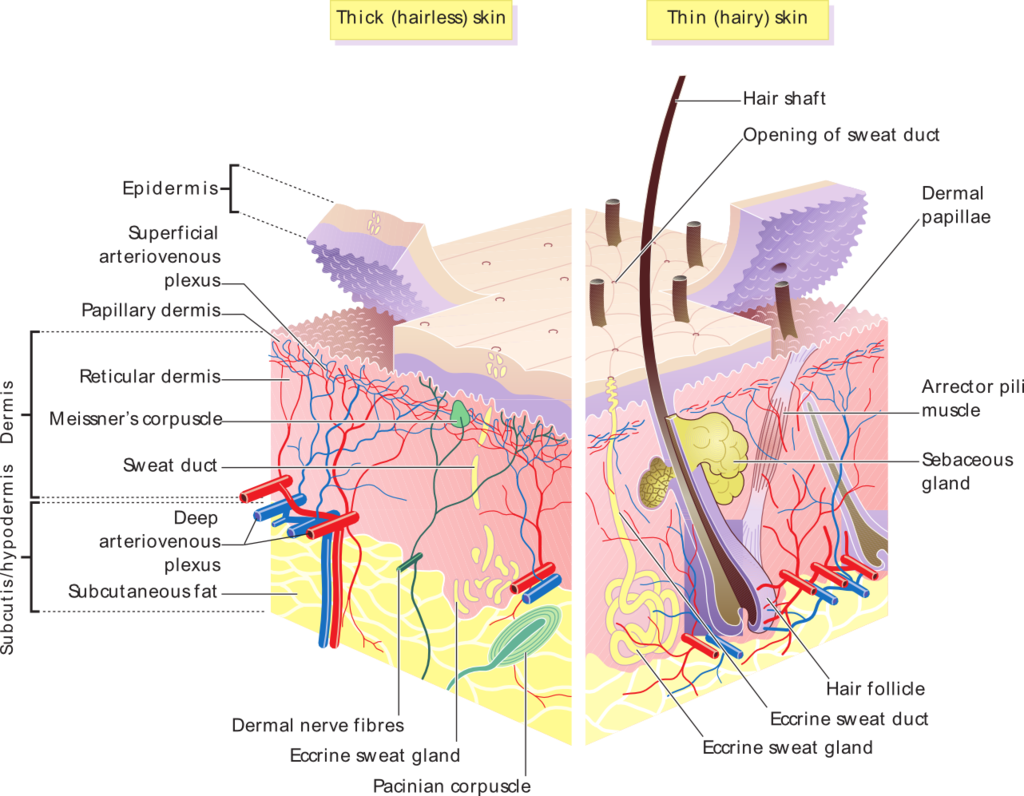

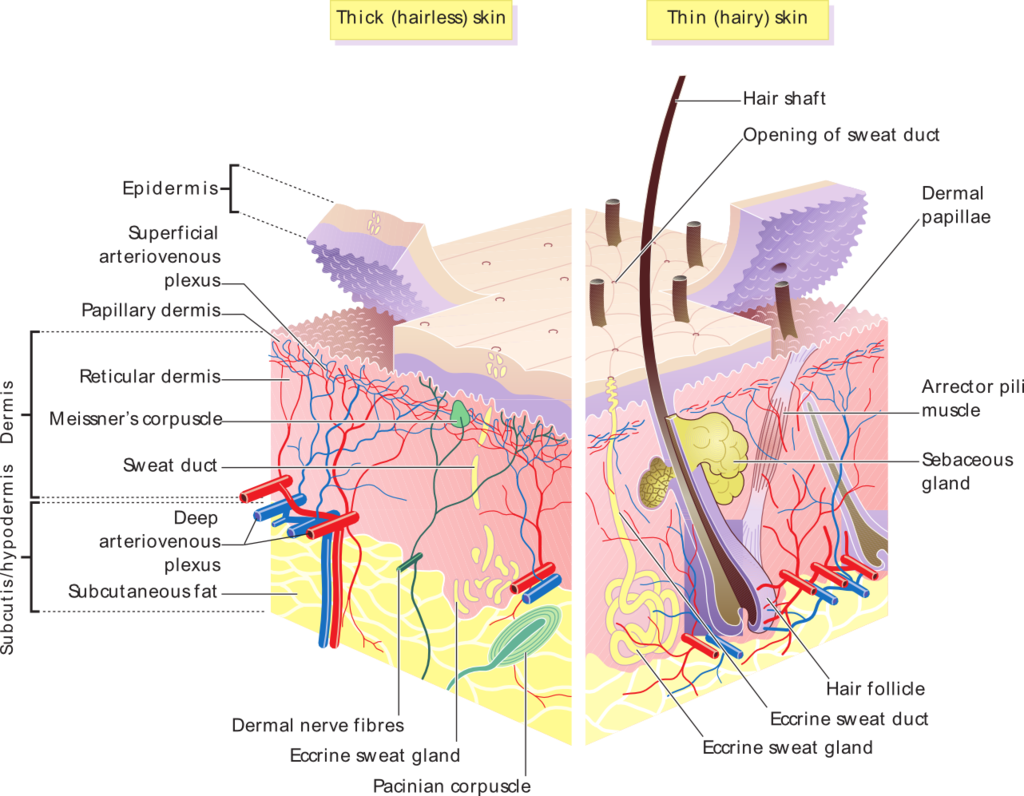

The outer layer of skin, the epidermis, provides waterproofing and serves as a barrier to infection.

The middle layer of skin, the dermis, contains blood vessels, nerves, and glands that are important for our skin’s function. The inner layer of the skin, the subcutis, contains fat that protects us from trauma.

Key Terms

epidermis: The outermost layer of the skin.

subcutis: The inner layer of skin that is also called the hypodermis or subcutaneous layer.

dermis: The middle layer of the skin.

cutaneous membrane: The formal name for the skin.

The Cutaneous Membrane

The cutaneous membrane is the technical term for our skin. The skin’s primary role is to help protect the rest of the body’s tissues and organs from physical damage such as abrasions, chemical damage such as detergents, and biological damage from microorganisms. For example, while the skin harbors many permanent and transient bacteria, these bacteria are unable to enter the body when healthy, intact skin is present.

Our skin is made of three general layers. In order from most superficial to deepest they are the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue.

The Epidermis

The epidermis is a thin layer of skin. It is the most superficial layer of skin, the layer you see with your eyes when you look at the skin anywhere on your body. Functions of the epidermis include touch sensation and protection against microorganisms.

This skin is further divided into five, separate layers. In order from most superficial to deepest, they are the:

- Stratum Corneum

- Stratum Lucidum

- Stratum Granulosum

- Stratum Spinosum

- Stratum Basale

Stratum Corneum

This layer is composed of the many dead skin cells that you shed into the environment—as a result, these cells are found in dust throughout your home. This layer helps to repel water.

Stratum Lucidum

This layer is found only on the palms of the hands, fingertips, and the soles of the feet.

Stratum Granulosum

This is the layer where part of keratin production occurs. Keratin is a protein that is the main component of skin.

Stratum Spinosum

This layer gives the skin strength as well as flexibility.

Stratum Basale

This is where the skin’s most important cells, called keratinocytes, are formed before moving up to the surface of the epidermis and being shed into the environment as dead skin cells.

This layer also contains melanocytes, the cells that are largely responsible for determining the color of our skin and protecting our skin from the harmful effects of UV radiation. These harmful effects include burns in the short term and cancer in the long run.

The Dermis

Underneath the epidermis lies the dermis. The dermis contains:

- Blood vessels that nourish the skin with oxygen and nutrients. The blood vessels also allow immune system cells to come to the skin to fight an infection. These vessels also help carry away waste products.

- Nerves that help us relay signals coming from the skin. These signals include touch, temperature, pressure, pain, and itching.

- Various glands.

- Hair follicles.

- Collagen, a protein that is responsible for giving skin strength and a bit of elasticity.

The Subcutaneous Tissue

The deepest layer of the skin is called the subcutaneous layer, the subcutis, or the hypodermis. Like the dermis, the layer contains blood vessels and nerves for much the same reasons.

Importantly, the subcutis contains a layer of fat. This layer of fat works alongside the blood vessels to maintain an appropriate body temperature. The layer of fat here acts as a cushion against physical trauma to internal organs, muscles, and bones.

Additionally, the body will turn to this fat in times of starvation to provide power to its various processes, especially brain function.

Layers of cutaneous membranes (skin): This image details features of the epidermal and dermal layers of the skin.

Structure of the Skin: Epidermis

The epidermis includes five main layers: the stratum corneum, stratum lucidium, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum germinativum.

Key Points

The epidermis provides a protective waterproof barrier that also keeps pathogens at bay and regulates body temperature.

The main layers of the epidermis are: stratum corneum, stratum lucidium, stratum granulosm, stratum spinosum, stratum germinativum (also called stratum basale).

Keratinocytes in the stratum basale proliferate during mitosis and the daughter cells move up the strata, changing shape and composition as they undergo multiple stages of cell differentiation.

Key Terms

keratinocyte: The predominant cell type in the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin, constituting 95% of the cells found there. Those keratinocytes found in the basal layer (stratum germinativum) of the skin are sometimes referred to as basal cells or basal keratinocytes.

stratum germinativum: The basal layer—sometimes referred to as stratum basale—is the deepest of the five layers of the epidermis.

stratum corneum: The most superficial layer of the epidermis from which dead skin sheds.

epidermis: The outermost layer of skin.

stratum lucidum: A layer of our skin that is found on the palms of our hands and the soles of our feet.

Layers of the Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost layer of our skin. It is the layer we see with our eyes. It contains no blood supply of its own—which is why you can shave your skin and not cause any bleeding despite losing many cells in the process. Assuming, that is, you don’t nick your skin to deep, where the blood supply is actually found.

The epidermis is itself divided into at least four separate parts. A fifth part is present in some areas of our body. In order from the deepest layer of the epidermis to the most superficial, these layers (strata) are the:

- Stratum basale

- Stratum spinosum

- Stratum granulosum

- Stratum lucidum

- Stratum corneum

Skin overview: Skin layers, of both hairy and hairless skin.

Stratum Basale

Human skin: This image details the parts of the integumentary system.

The stratum basale, also called the stratum germinativum, is the basal (base) layer of the epidermis. It is the layer that’s closest to the blood supply lying underneath the epidermis.

This layer is one of the most important layers of our skin. This is because it contains the only cells of the epidermis that can divide via the process of mitosis, which means that skin cells germinate here, hence the word germinativum.

In this layer, the most numerous cells of the epidermis, called keratinocytes, arise thanks to mitosis. Keratinocytes produce the most important protein of the epidermis.

This protein is appropriately called keratin. Keratin makes our skin tough and provides us with much-needed protection from microorganisms, physical harm, and chemical irritation.

Millions of these new cells arise in the stratum basale on a daily basis. The newly produced cells push older cells into the upper layers of the epidermis with time. As these older cells move up toward the surface, they change their shape, nuclear, and chemical composition. These changes are, in part, what give the strata their unique characteristics.

Stratum Spinosum and Granulosum

Layers of the epidermis: The epidermis is made up of 95% keratinocytes but also contains melanocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells, and inflammatory cells. The stratum basale is primarily made up of basal keratinocyte cells, which can be considered the stem cells of the epidermis. They divide to form the keratinocytes of the stratum spinosum, which migrate superficially.

From the stratum basale, the keratinocytes move into the stratum spinosum, a layer so called because its cells are spiny-shaped cells. The stratum spinosum is partly responsible for the skin’s strength and flexibility.

From there the keratinocytes move into the next layer, called the stratum granulosum. This layer gets its name from the fact that the cells located here contain many granules.

The keratinocytes produce a lot of keratin in this layer—they become filled with keratin. This process is known as keratinization. The keratinocytes become flatter, more brittle, and lose their nuclei in the stratum granulosum as well.

Stratum Lucidum

Once the keratinocytes leave the stratum granulosum, they die and help form the stratum lucidum. This death occurs largely as a result of the distance the keratinocytes find themselves from the rich blood supply the cells of the stratum basale lie on top off. Devoid of nutrients and oxygen, the keratinocytes die as they are pushed towards the surface of our skin.

The stratum lucidum is a layer that derives its name from the lucid (clear/transparent) appearance it gives off under a microscope. This layer is only easily found in certain hairless parts of our body, namely the palms of our hands and the soles of our feet. Meaning, the places where our skin is usually the thickest.

Stratum Corneum

From the stratum lucidum, the keratinocytes enter the next layer, called the stratum corneum (the horny layer filled with cornified cells). This the only layer of skin we see with our eyes.

The keratinocytes in this layer are called corneocytes. They are devoid of almost all of their water and they are completely devoid of a nucleus at this point. They are dead skin cells filled with the tough protein keratin. In essence, they are a protein mass more so than they are a cell.

The corneocytes serve as a hard protective layer against environmental trauma, such as abrasions, light, heat, chemicals, and microorganisms. The cells of the stratum corneum are also surrounded by lipids (fats) that help repel water as well. These corneocytes are eventually shed into the environment and become part of dandruff in our hair or the dust around us, which dust mites readily munch on.

This entire cycle, from a new keratinocyte in the stratum basale to a dead cell flaked off into the air, takes between 25–45 days.

Structure of the Skin: Dermis

The dermis consists of a papillary and a reticular layer that serves to protect and cushion the body from stress and strain.

Skin has three layers: The epidermis, the outermost layer of skin, provides a waterproof barrier and creates our skin tone. The dermis, beneath the epidermis, contains tough connective tissue, hair follicles, and sweat glands. The deeper subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis) is made of fat and connective tissue

Key Points

The dermis is divided into a papillary region and a reticular region.

The primary function of the dermis is to cushion the body from stress and strain, and to also provide: elasticity to the skin, a sense of touch, and heat.

The dermis contains hair roots, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, nerves, and blood vessels.

The hypodermis lies below the dermis and contains a protective layer of fat.

Key Terms

the reticular layer: The deepest layer of the dermis.

hypodermis: A subcutaneous layer of loose connective tissue containing fat cells, lying beneath the dermis.

the dermis: The layer of skin underneath the epidermis.

the papillary layer: The most superficial layer of the dermis.

The Dermis

Lying underneath the epidermis—the most superficial layer of our skin—is the dermis (sometimes called the corium). The dermis is a tough layer of skin. It is the layer of skin you touch when buying any leather goods.

The dermis is composed of two layers. They are the papillary layer (the upper layer) and the reticular layer (the lower layer).

The Papillary Layer

Human Skin: This image details the parts of the integumentary system.

The papillary layer provides the layer above it, the epidermis, with nutrients to produce skin cells called keratinocytes. It also helps regulate the temperature of our skin and thus the body as a whole.

Both the nutrient supply and temperature regulation occur thanks to an extensive network of blood vessels in this layer. These blood vessels also help remove cellular waste products that would otherwise kill the skin cells if they were allowed to accumulate.

The pink tint to the skin of light-skinned individuals is due to the blood vessels found here. In fact, when you blush, it is the dilation of these blood vessels that causes you to turn red. The uneven projections found in this layer, called dermal papillae, also form people’s fingerprints and give this layer its name.

The Reticular Layer

The reticular layer serves to strengthen the skin and also provides our skin with elasticity. Elasticity refers to how our skin is able to spring back into shape if deformed by something like a pinch. The reticular layer also contains hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands.

The sweat gland can either be apocrine, such as those found in the armpits and the groin area, or the eccrine glands, which are found all over the body. The former help contribute to body odor (along with the bacteria on our skin), and the latter help regulate our body temperature through the process of evaporation.

The sebaceous glands found in the dermis secrete a substance called sebum that helps to lubricate and protect our skin from drying out.

The dermis also contains:

- Nerve endings that transmit various stimuli such as pain, itch, pressure, and temperature.

- Lymphatic vessels that transport immune system cells, the cells that help destroy infectious organisms that may have found their way into our body via a scratch on the skin.

- Collagen, a protein that helps strengthen our skin, and elastin, a protein that helps keep our skin flexible.

The Hypodermis

Beneath the dermis is the deepest layer of our skin. It is alternatively termed hypodermis, subcutis, or subcutaneous tissue. It contains many collagen cells as well as fat.

Fat, in particular, helps insulate our body from the cold and act as a cushion for our internal structures (such as muscles and organs) when something hits us. Fat can also be called upon by the body in times of great need as an energy source.

Given the alternative names for this layer, it should come as no surprise that this is the layer where subcutaneous injections are given into via a hypodermic needle.

Skin sensory receptors: Those nearest the surface of the skin include receptors that detect gentle pressure, temperature, and vibrations, as well as naked nerve endings (dendrites) that detect pain. Deeper in the dermis are naked dendrites that wind around the bases of hair follicles and detect motions of the hairs, as well as receptors such as Pacinian corpuscles that respond to strong pressure and vibrations.

Skin Color

Skin color is determined largely by the amount of melanin pigment produced by melanocytes in the skin.

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one’s biological parents), exposure to the sun, or both.

Key Points

Skin color is mainly determined by a pigment called melanin.

Melanin is produced by melanocytes through a process called melanogenesis.

The difference in skin color between lightly and darkly pigmented individuals is due to their level of melanocyte activity; it is not due to the number of melanocytes in their skin.

Key Terms

melanin: Any of a group of naturally occurring dark pigments responsible for the color of skin.

melanocyte: A cell in the skin that produces the pigment melanin.

keratinocytes: Cells that take up and store melanin.

eumelanin: The type of melanin mainly responsible for brown and black skin.

stratum basale: The epidermal layer where melanocytes are found.

Melanin

Skin color is largely determined by a pigment called melanin but other things are involved. Your skin is made up of three main layers, and the most superficial of these is called the epidermis. The epidermis itself is made up of several different layers.

Melanocyte: Cross-section of skin showing melanin in melanocytes

The deepest of the epidermal layers is called the stratum basale or stratum germinativum. In this layer lie important cells called melanocytes. Their name is derived from two parts: melano-, which means black or darkness, and -cyte, which means cell.

Melanocytes are irregularly shaped cells that produce and store a pigment called melanin. The most abundant type of melanin is called eumelanin. This pigment is stored in organelles called melanosomes.

Eumelanin is responsible for the brown and black pigmentation of human skin or the lack thereof if little of it is produced. The production of melanin is called melanogenesis—genesis means formation or development.

How Skin Color is Determined

Regardless of background, every person has largely the same number of melanocytes, but the genetics of each person is what determines how much melanin is produced and how it is distributed throughout the skin. For example, light skinned individuals may have darker places like nipples and moles. Conversely, dark skinned individuals have a lighter tone to the palms of their hands.

Another critical factor, exposure to sunlight, triggers the production of melanin as well. This is what gives us a tan. The melanin produced in response to the sun’s rays protects our skin and the rest of the body from the harmful effects of the sun’s burn and cancer-inducing U.V. radiation.

The Role of Keratinocytes

People with darker skin have more active melanocytes compared to people with lighter skin. However, the pigment of our skin also involves the most abundant cells of our epidermis, the keratinocytes.

While melanocytes produce, store, and release melanin, keratinocytes are the largest recipients of this pigment. The transfer of melanin from melanocytes to keratinocytes occurs thanks to the long tentacles each melanocyte extends to upwards of 40 keratinocytes.

If a person is unable to produce melanin, they have a condition called albinism.

Other Skin Color Determinant

Besides melanin, other factors play a role in general or local skin color. These include:

- The amount of carotene found in the stratum corneum of the epidermis and the deepest layer of the skin, the hypodermis. Carotene is a yellow-orange pigment found in carrots. Your skin may turn this color if you eat a lot of carotene-rich foods. The skin may turn yellow due to another factor, called icterus or jaundice, which occurs with serious liver disease. In this instance, bile pigments are deposited within the skin and impart a yellow color to it.

- The amount of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin found in the blood vessels of the middle layer of our skin, the dermis. Hemoglobin is the iron-containing protein pigment of our blood cells. A lack of oxygen saturation imparts a paler, grayer, or bluer color to the skin. Skin may also become paler as a result of anemia (a reduced number of hemoglobin and/or red blood cells), low blood pressure, or poor circulation of blood.

- Conversely, light-skinned individuals (compared to dark-skinned ones) may have a rosy effect to their skin thanks to the relatively more oxygen-rich hemoglobin flowing through the blood vessels of their dermis. Red-colored skin may also occur as a result of blood vessels in or near the skin dilating (expanding) due to embarrassment, fever, allergy, or inflammation.

- Finally, the skin may have red, black, blue, purple, and green bruises—all as a result of the escape of blood into surrounding tissues. As the blood (namely, the hemoglobin) disintegrates and is processed and removed by various cells, it and the bruise changes color with time.

Skin Conditions

- Rash: Nearly any change in the skin’s appearance can be called a rash. Most rashes are from simple skin irritation; others result from medical conditions.

- Dermatitis: A general term for inflammation of the skin. Atopic dermatitis (a type of eczema) is the most common form.

- Eczema: Skin inflammation (dermatitis) causing an itchy rash. Most often, it’s due to an overactive immune system.

- Psoriasis: An autoimmune condition that can cause a variety of skin rashes. Silver, scaly plaques on the skin are the most common form.

- Dandruff: A scaly condition of the scalp may be caused by seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or eczema.

- Acne: The most common skin condition, acne affects over 85% of people at some time in life.

- Cellulitis: Inflammation of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues, usually due to an infection. A red, warm, often painful skin rash generally results.

- Skin abscess (boil or furuncle): A localized skin infection creates a collection of pus under the skin. Some abscesses must be opened and drained by a doctor in order to be cured.

- Rosacea: A chronic skin condition causing a red rash on the face. Rosacea may look like acne, and is poorly understood.

- Warts: A virus infects the skin and causes the skin to grow excessively, creating a wart. Warts may be treated at home with chemicals, duct tape, or freezing, or removed by a physician.

- Melanoma: The most dangerous type of skin cancer, melanoma results from sun damage and other causes. A skin biopsy can identify melanoma.

- Basal cell carcinoma: The most common type of skin cancer. Basal cell carcinoma is less dangerous than melanoma because it grows and spreads more slowly.

- Seborrheic keratosis: A benign, often itchy growth that appears like a “stuck-on” wart. Seborrheic keratoses may be removed by a physician, if bothersome.

- Actinic keratosis: A crusty or scaly bump that forms on sun-exposed skin. Actinic keratoses can sometimes progress to cancer.

- Squamous cell carcinoma: A common form of skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma may begin as an ulcer that won’t heal, or an abnormal growth. It usually develops in sun-exposed areas.

- Herpes: The herpes viruses HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause periodic blisters or skin irritation around the lips or the genitals.

- Hives: Raised, red, itchy patches on the skin that arise suddenly. Hives usually result from an allergic reaction.

- Tinea versicolor: A benign fungal skin infection creates pale areas of low pigmentation on the skin.

- Viral exantham: Many viral infections can cause a red rash affecting large areas of the skin. This is especially common in children.

- Shingles (herpes zoster): Caused by the chickenpox virus, shingles is a painful rash on one side of the body. A new adult vaccine can prevent shingles in most people.

- Scabies: Tiny mites that burrow into the skin cause scabies. An intensely itchy rash in the webs of fingers, wrists, elbows, and buttocks is typical of scabies.

- Ringworm: A fungal skin infection (also called tinea). The characteristic rings it creates are not due to worms.

Skin Tests

- Skin biopsy: A piece of skin is removed and examined under a microscope to identify a skin condition.

- Skin testing (allergy testing): Extracts of common substances (such as pollen) are applied to the skin, and any allergic reactions are observed.

- Tuberculosis skin test (purified protein derivative or PPD): Proteins from the tuberculosis (TB) bacteria are injected under the skin. In someone who’s had TB, the skin becomes firm.

Skin Treatments

- Corticosteroids (steroids): Medicines that reduce immune system activity may improve dermatitis. Topical steroids are most often used.

- Antibiotics: Medicines that can kill the bacteria causing cellulitis and other skin infections.

- Antiviral drugs: Medicines can suppress the activity of the herpes virus, reducing symptoms.

- Antifungal drugs: Topical creams can cure most fungal skin infections. Occasionally, oral medicines may be needed.

- Antihistamines: Oral or topical medicines can block histamine, a substance that causes itching.

- Skin surgery: Most skin cancers must be removed by surgery.

- Immune modulators: Various drugs can modify the activity of the immune system, improving psoriasis or other forms of dermatitis.

- Skin moisturizers (emollients): Dry skin is more likely to become irritated and itchy. Moisturizers can reduce symptoms of many skin conditions.

Visitor Rating: 4 Stars