Stable angina/Angina pectoris (Latin for squeezing of the chest) – is chest pain, discomfort, or tightness that occurs when an area of the heart muscle is receiving decreased blood oxygen supply. It is not a disease itself, but rather a symptom of coronary artery disease, the most common type of heart disease.

Angina is a Latin word describing a spasmodic, cramplike, choking feeling or suffocating pain; pectoris is the Latin word for chest. These words aptly describe the basic clinical manifestations of angina pectoris, commonly called angina, the classic expression of ischemic heart disease. The term angina pectoris was first used in 1768 in a lecture by Dr. William Heberden to distinguish the “strangling” sensation of angina from the word dolor, which means pain. A definition of angina is “a characteristic thoracic pain, usually substernal; precipitated chiefly by exercise, emotion, or a heavy meal; relieved by vasodilator drugs and a few minutes’ rest; and a result of a moderate inadequacy of the coronary circulation.”1 Another description of angina states that it is a “discomfort in the chest or adjacent areas caused by myocardial ischemia. It is usually brought on by exertion and associated with a disturbance in myocardial function, but without myocardial necrosis.” The major clinical characteristic of angina is chest pain. However, the word “pain” is seldom used by the victim.

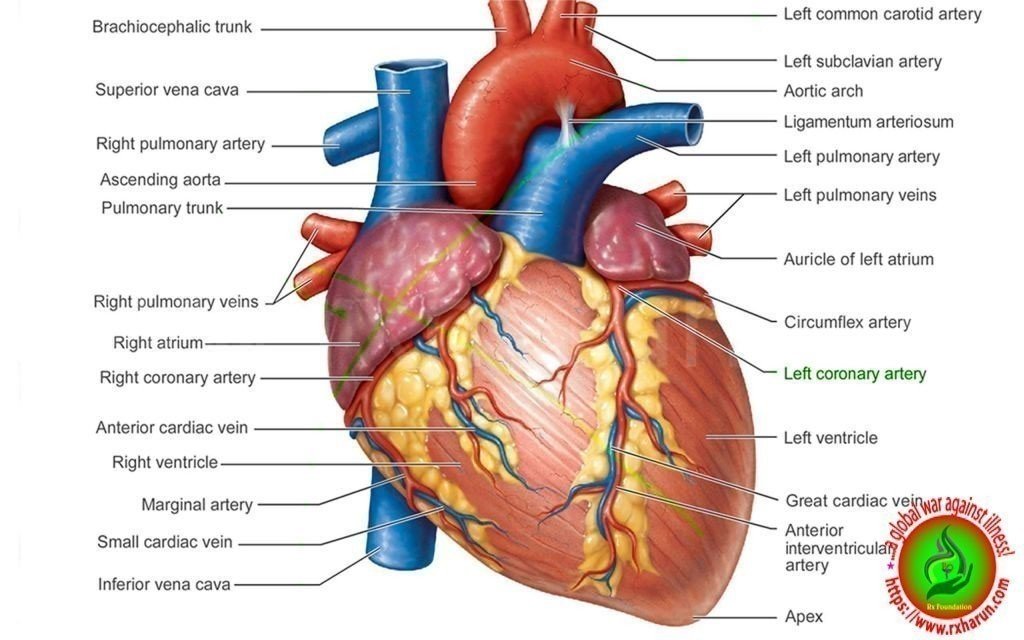

The lack of oxygen rich blood to the heart is usually a result of narrower coronary arteries due to plaque buildup, a condition called atherosclerosis. Narrow arteries increase the risk of pain, coronary artery disease, heart attack, and death.

Types of Angina Pectoris

- Unstable angina – is characterized by sudden pain that doesn’t go away on its own or respond to rest or medication. This type is caused by a blood clot that blocks the blood vessel, and it will cause a heart attack if the blockage isn’t removed.

- Stable angina – is characterized by regular episodes of pain triggered by physical exercise or activity, smoking, eating large meals, or extreme temperatures. This occurs because the arteries have accumulated deposits, narrowing the pathway for blood to move through.

- Variant angina – is caused by a spasm in a coronary artery, causing it to temporarily narrow. This is a specific form of unstable angina that can occur at any time (no trigger event causes it to happen).

- Silent ischemia – Patients with coronary artery disease (particularly patients with diabetes) may have ischemia without symptoms. Silent ischemia sometimes manifests as transient asymptomatic ST-T abnormalities seen during stress testing or 24-h Holter monitoring. Radionuclide studies can sometimes document asymptomatic myocardial ischemia during physical or mental stress. Silent ischemia and angina pectoris may coexist, occurring at different times. Prognosis depends on severity of the coronary artery disease.

- Nocturnal angina – May occur if a dream causes striking changes in respiration, pulse rate, and BP. Nocturnal angina may also be a sign of recurrent LV failure, an equivalent of nocturnal dyspnea. The recumbent position increases venous return, stretching the myocardium and increasing wall stress, which increases oxygen demand.

- Angina decubitus – Is angina that occurs spontaneously during rest. It is usually accompanied by a modestly increased heart rate and a sometimes markedly higher BP, which increase oxygen demand. These increases may be the cause of rest angina or the result of ischemia induced by plaque rupture and thrombus formation. If angina is not relieved, unmet myocardial oxygen demand increases further, making MI more likely.

Causes of Angina Pectoris

Your heart muscle needs a constant supply of oxygen. The coronary arteries carry blood containing oxygen to the heart.

When the heart muscle has to work harder, it needs more oxygen. Symptoms of angina occur when the coronary arteries are narrowed or blocked by atherosclerosis or by a blood clot.

The most common cause of angina is coronary artery disease. Angina pectoris is the medical term for this type of chest pain.

Stable angina is less serious than unstable angina, but it can be very painful or uncomfortable.

There are many risk factors for coronary artery disease. Some include:

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure

- High LDL cholesterol and low HDL cholesterol

- Smoking

- Anything that makes the heart muscle need more oxygen or reduces the amount of oxygen it receives can cause an angina attack in someone with heart disease, including:

- Cold weather

- Exercise

- Emotional stress

- Large meals

Other causes of angina include

- Abnormal heart rhythms (your heart beats very quickly or your heart rhythm is not regular)

- Anemia

- Coronary artery spasm (also called Prinzmetal’s angina)

- Heart failure

- Heart valve disease

- Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid)

Major Causes of Angina

- Age (≥ 45 years for men, ≥ 55 for women)

- Smoking

- Diabetes mellitus

- Dyslipidemia

- Family history of premature cardiovascular disease (men <55 years, female <65 years old)

- Hypertension

- Kidney disease (microalbuminuria or GFR<60 mL/min)

- Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)

- Physical inactivity

- Prolonged psychosocial stress[17]

- Conditions that exacerbate or provoke angina

- Medications

- Vasodilators

- Excessive thyroid hormone replacement

- Vasoconstrictors

- Polycythemia, which thickens the blood, slowing its flow through the heart muscle

- Hypothermia

- Hypervolemia

- Hypovolemia

Other medical problems

- Esophageal disorders

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypoxemia

- Profound anemia

- Uncontrolled hypertension

Other cardiac problems

- Bradyarrhythmia

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Tachyarrhythmia

- Valvular heart disease[24][25]

Myocardial ischemia can result from

- A reduction of blood flow to the heart that can be caused by stenosis, spasm, or acute occlusion (by an embolus) of the heart’s arteries.

- The resistance of the blood vessels. This can be caused by narrowing of the blood vessels; a decrease in radius.[26] Blood flow is proportional to the radius of the artery to the fourth power.[27]

- Reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, due to several factors such as a decrease in oxygen tension and hemoglobin concentration.[28] This decreases the ability of hemoglobin to carry oxygen to myocardial tissue.[29]

- Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of stenosis (narrowing of the blood vessels) of the heart’s arteries and, hence, angina pectoris. Some people with chest pain have normal or minimal narrowing of heart arteries; in these patients, vasospasm is a more likely cause for the pain, sometimes in the context of Prinzmetal’s angina and syndrome X.

- Myocardial ischemia also can be the result of factors affecting blood composition, such asthe reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of blood, as seen with severe anemia (low number of red blood cells), or long-term smoking.

Other causes of angina include

- Abnormal heart rhythms (your heart beats very quickly or your heart rhythm is not regular)

- anemia

- Coronary artery spasm (also called Prinzmetal’s angina)

- Heart failure

- Heart valve disease

- Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid)

Symptoms of Angina pectoris

Patients should be asked about the frequency of angina, severity of pain, and number of nitroglycerin pills used during episodes. Symptomatology reported by patients with angina commonly includes the following:

-

Retrosternal chest discomfort (pressure, heaviness, squeezing, burning, or choking sensation) as opposed to frank pain

-

Pain localized primarily in the epigastrium, back, neck, jaw, or shoulders

-

Pain precipitated by exertion, eating, exposure to cold, or emotional stress, lasting for about 1-5 minutes and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin

-

Pain intensity that does not change with respiration, cough, or change in position

Typically, the chest pain feel like tightness, heavy pressure, squeezing, or a crushing feeling. It may spread to the:

- Arm (most often the left)

- Back

- Jaw

- Neck

- Shoulder

Some people say the pain feels like gas or indigestion.

Less common symptoms of angina may include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Weakness

- Dizziness or light-headedness

- Nausea, vomiting, and sweating

- Palpitations

Pain from stable angina:

- Most often comes on after activity or stress

- Lasts an average of 1 to 15 minutes

- Is relieved with rest or a medicine called nitroglycerin

Angina attacks can occur at any time during the day. Most occur between 6 a.m. and noon.

Angina decubitus (a variant of angina pectoris that occurs at night while the patient is recumbent) may occur.

The following should be taken into account in the physical examination

-

For most patients with stable angina, physical examination findings are normal

-

A positive Levine sign suggests angina pectoris

-

Signs of abnormal lipid metabolism or of diffuse atherosclerosis may be noted

-

Examination of patients during the angina attack may be more helpful

-

Pain produced by chest wall pressure is usually of chest wall origin

-

Myocardial ischemia comes about when the myocardium (the heart muscle) receives insufficient blood and oxygen to function normally either because of increased oxygen demand by the myocardium or because of decreased supply to the myocardium.

-

This inadequate perfusion of blood and the resulting reduced delivery of oxygen and nutrients are directly correlated to blocked or narrowed blood vessels.

-

Some experience “autonomic symptoms” (related to increased activity of the autonomic nervous system) such as nausea, vomiting, and pallor.

-

Major risk factors for angina include cigarette smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle, and family history of premature heart disease.

-

A variant form of angina—Prinzmetal’s angina—occurs in patients with normal coronary arteries or insignificant atherosclerosis. It is believed caused by spasms of the artery. It occurs more in younger women.[15]

Diagnosis of Angina pectoris

Diagnostic studies that may be employed include the following

-

Chest radiography: Usually normal in angina pectoris but may show cardiomegaly in patients with previous MI, ischemic cardiomyopathy, pericardial effusion, or acute pulmonary edema

-

Graded exercise stress testing: This is the most widely used test for the evaluation of patients presenting with chest pain and can be performed alone and in conjunction with echocardiography or myocardial perfusion scintigraphy

-

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring by fast CT: The primary fast CT methods for this application are electron-beam CT (EBCT) and multidetector CD (MDCT)

Other tests that may be useful include the following

-

ECG (including exercise with ECG monitoring and ambulatory ECG monitoring)

-

Selective coronary angiography (the definitive diagnostic test for evaluating the anatomic extent and severity of CAD)

-

Asymptomatic high-risk patients or patients with atypical or typical angina who have inconclusive exercise stress test results, cannot undergo exercise stress testing, or need to undergo major noncardiac surgery

Patients in whom invasive coronary angiography was unable to locate a major coronary artery or graft

- Electron beam CT – Can detect the amount of calcium present in coronary artery plaque. The calcium score (from 1 to 100) is roughly proportional to the risk of subsequent coronary events. However, because calcium may be present in the absence of significant stenosis, the score does not correlate well with the need for angioplasty or CABG. Thus, the American Heart Association recommends that screening with electron beam CT should be done only for select groups of patients and is most valuable when combined with historical and clinical data to estimate risk of death or nonfatal MI.

- Cardiac MRI – Has become invaluable in evaluating many cardiac and great vessel abnormalities. It may be used to evaluate CAD by several techniques, which enable direct visualization of coronary stenosis, assessment of flow in the coronary arteries, evaluation of myocardial perfusion and metabolism, evaluation of wall motion abnormalities during stress, and assessment of infarcted myocardium vs viable myocardium.

- Multidetector row CT (MDRCT) coronary angiography – Can accurately identify coronary stenosis and has a number of advantages. The test is noninvasive, can exclude coronary stenosis with high accuracy, can establish stent or bypass graft patency, can show cardiac and coronary venous anatomy, and can assess calcified and noncalcified plaque burden. However, radiation exposure is significant, and the test is not suitable for patients with a heart rate of >65 beats/min, those with irregular heart beats, and pregnant women. Patients must also be able to hold their breath for 15 to 20 sec, 3 to 4 times during the study.

- Stress testing – is needed to confirm the diagnosis, evaluate disease severity, determine appropriate exercise levels for the patient, and help predict prognosis. If the clinical or working diagnosis is unstable angina, early stress testing is contraindicated.

- For CAD – the most accurate tests are stress echocardiography and myocardial perfusion imaging with single-photon emission CT (SPECT) or PET. However, these tests are more expensive than simple stress testing with ECG.

Angiography

- Intravascular ultrasonography – Provides images of coronary artery structure. An ultrasound probe on the tip of a catheter is inserted in the coronary arteries during angiography. This test can provide more information about coronary anatomy than other tests; it is indicated when the nature of lesions is unclear or when apparent disease severity does not match symptom severity. Used with angioplasty, it can help ensure optimal placement of stents.

- Coronary angiography – Is the standard for diagnosing CAD but is not always necessary to confirm the diagnosis. It is indicated primarily to locate and assess severity of coronary artery lesions when revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) is being considered. Angiography may also be indicated when knowledge of coronary anatomy is necessary to advise about work or lifestyle needs (eg, discontinuing job or sports activities).

- Guidewires with pressure or flow sensors can be used to estimate blood flow across stenoses. Blood flow is expressed as fractional flow reserve (FFR), which is the ratio of maximal flow through the stenotic area to normal maximal flow. These flow measurements are most useful when evaluating the need for angioplasty or CABG in patients with lesions of questionable severity (40 to 70% stenosis). An FFR of 1.0 is considered normal, while an FFR < 0.75 to 0.8 is associated with myocardial ischemia. Lesions with an FFR > 0.8 are less likely to benefit from stent placement.

Imaging

- Cardiac MRI – Has become invaluable in evaluating many cardiac and great vessel abnormalities. It may be used to evaluate CAD by several techniques, which enable direct visualization of coronary stenosis, assessment of flow in the coronary arteries, evaluation of myocardial perfusion and metabolism, evaluation of wall motion abnormalities during stress, and assessment of infarcted myocardium vs viable myocardium

- Electron beam CT – Can detect the amount of calcium present in coronary artery plaque. The calcium score (from 1 to 100) is roughly proportional to the risk of subsequent coronary events. However, because calcium may be present in the absence of significant stenosis, the score does not correlate well with the need for angioplasty or CABG. Thus, the American Heart Association recommends that screening with electron beam CT should be done only for select groups of patients and is most valuable when combined with historical and clinical data to estimate risk of death or nonfatal MI. These groups may include asymptomatic patients with an intermediate Framingham 10-yr risk estimate of 10 to 20% and symptomatic patients with equivocal stress test results. Electron beam CT is particularly useful in ruling out significant CAD in patients presenting to the emergency department with atypical symptoms, normal troponin levels, and a low probability of hemodynamically significant coronary disease. These patients may have noninvasive testing as outpatients.

- Multidetector row CT (MDRCT) coronary angiography – can accurately identify coronary stenosis and has a number of advantages. The test is noninvasive, can exclude coronary stenosis with high accuracy, can establish stent or bypass graft patency, can show cardiac and coronary venous anatomy, and can assess calcified and noncalcified plaque burden. However, radiation exposure is significant, and the test is not suitable for patients with a heart rate of >65 beats/min, those with irregular heart beats, and pregnant women. Patients must also be able to hold their breath for 15 to 20 sec, 3 to 4 times during the study.

Treatment Angina Pectoris

General treatment measures include the following

Self-management

Because angina can be triggered by physical exertion, anxiety or emotional stress, cold weather, or eating a heavy meal, the following behavioural changes may help to alleviate angina symptoms:

- rest as soon as you feel symptoms coming on

- pace yourself and take regular breaks

- reduce and manage stress

- keep warm

- avoid eating large meals.

Risk factors for coronary artery disease include high blood pressure and cholesterol levels, tobacco smoking, diabetes, excess weight, and low levels of physical activity. Hence, the following lifestyle changes can help to minimise angina symptoms and improve your heart’s health:

- stop smoking and avoid second-hand smoke and avoid second-hand smoke

- control high blood pressure or high blood cholesterol levels

- exercise moderately and regularly, especially healthy heart exercise (always consult a health professional before commencing a new exercise regime)

- maintain a healthy weight

- eat a healthy heart diet

- manage diabetes

- avoid drinking alcohol or do so in moderation.

- Lifestyle changes

- Such as coronary angiography with stent placement

- Coronary artery bypass surgery

| Drug | Indications | Mechanism | Adverse effects | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrates (short- and long-acting) | Relief of acute or anticipated pain (short-acting) Prevention of angina (long-acting) |

Systemic and coronary vasodilation | Headache Hypotension Syncope Reflex tachycardia |

Avoid sildenafil and similar drugs Tolerance with long-acting nitrates |

| Beta blockers | First-line therapy for exertional angina and after myocardial infarction | Reduce blood pressure, heart rate and contractility Prolongs diastolic filling time |

Fatigue Altered glucose Bradycardia Heart block Impotence Bronchospasm Peripheral vasoconstriction Hypotension Insomnia or nightmares |

Avoid with verapamil because of risk of bradycardia Avoid in asthma, 2nd and 3rd degree heart block and acute heart failure |

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists (e.g. amlodipine, felodipine, nifedipine) | Alternative, or in addition, to a beta blocker Coronary spasm |

Systemic and coronary vasodilator | Hypotension Peripheral oedema Headache Palpitations Flushing |

Avoid short-acting nifedipine because of reflex tachycardia and increased mortality in ischaemia |

| Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists (e.g. verapamil, diltiazem) | Alternative, or in addition, to a beta blocker | Arteriolar vasodilator Centrally acting drugs reduce heart rate, blood pressure, contractility, and prolong diastole |

Negative inotropic effect Bradycardia Heart block Constipation Hypotension Headache |

Avoid verapamil in heart failure and in combination with a beta blocker |

| Nicorandil | Angina | Systemic and coronary vasodilator | Headache Dizziness Nausea Hypotension Gastrointestinal ulceration |

Avoid sildenafil and similar drugs Metformin may reduce efficacy |

| Ivabradine | Angina Chronic heart failure |

Reduces heart rate | Visual disturbances Headache Dizziness Bradycardia Atrial fibrillation Heart block |

Caution with drugs that induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 Avoid in renal or hepatic failure |

| Perhexiline | Refractory angina | Favours anaerobic metabolism in active myocytes | Headache Dizziness Nausea, vomiting Visual change Peripheral neuropathy |

Narrow therapeutic range Need to monitor adverse effects and drug concentrations |

Medicines Drugs for Coronary Artery Disease

|

Drug |

Dosage |

Use |

||||||||||||||||

|

Drug |

Dosage |

Use |

||||||||||||||||

|

ACE inhibitors |

||||||||||||||||||

|

ACE inhibitors |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Benazepril Captopril Enalapril Fosinopril Lisinopril Moexipril Perindopril Quinapril Ramipril Trandolapril |

Variable |

All patients with CAD, especially those with large infarctions, renal insufficiency, heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes Contraindications include hypotension, hyperkalemia, bilateral renal artery stenosis, pregnancy, and known allergy |

||||||||||||||||

|

Angiotensin II receptor blockers Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) used in the UK

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Candesartan Eprosartan Irbesartan Losartan Olmesartan Telmisartan Valsartan |

Variable |

An effective alternative for patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors (eg, because of cough); currently, not first-line treatment after MI Contraindications include hypotension, hyperkalemia, bilateral renal artery stenosis, pregnancy, and known allergy |

||||||||||||||||

|

Anticoagulants |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Argatroban |

350 mcg/kg (IV bolus) followed by 25 mcg/kg/min (IV infusion) |

Patients with ACS and a known or suspected history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia as an alternative to heparin |

||||||||||||||||

|

Bivalirudin |

Variable |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Fondaparinux |

2.5 mg sc q 24 h |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Low molecular weight heparins:

|

Variable |

Patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI Patients < 75 yr receiving tenecteplase Almost all patients with STEMI as an alternative to unfractionated heparin (unless PCI is indicated and can be done in < 90 min); drug continued until PCI or CABG is done or patient is discharged |

||||||||||||||||

|

Unfractionated heparin |

60–70 units/kg IV (maximum, 5000 units; bolus), followed by 12–15 units/kg/h (maximum, 1000 units/h) for 3–4 days or until PCI is complete |

Patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI as an alternative to enoxaparin |

||||||||||||||||

|

60 units/kg IV (maximum, 4000 units; bolus) given when alteplase, reteplase, or tenecteplase is started, then followed by 12 units/kg/h (maximum,1000 units/h) for 48 h or until PCI is complete |

Patients who have STEMI and undergo urgent angiography and PCI or patients > 75 yr receiving tenecteplase |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Warfarin |

Oral dose adjusted to maintain INR of 2.5–3.5 |

May be useful long-term in patients at high risk of systemic emboli (ie, with large anterior MI, known LV thrombus, or atrial fibrillation) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Antiplatelet drugs |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Aspirin |

For stable angina†: 75 or 81 mg po once/day (enteric-coated) |

All patients with CAD or at high risk of developing CAD, unless aspirin is not tolerated or is contraindicated; used long-term |

||||||||||||||||

|

For ACS: 160–325 mg po chewed (not enteric-coated) on arrival at emergency department and once/day thereafter during hospitalization and 81 mg† po once/day long-term after discharge |

— |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Clopidogrel(preferred) |

75 mg po once/day |

Used with aspirin or, in patients who cannot tolerate aspirin, alone |

||||||||||||||||

|

For patients undergoing PCI: 300–600 mg po once, then 75 mg po once/day for 1–12 mo |

For patients undergoing PCI, clopidogrel loading dose to be administered only in cardiac catheterization laboratory after angiography has confirmed that coronary anatomy is amenable to PCI (so as not to delay CABG if indicated) Maintenance therapy required for at least 1 mo for bare-metal stents and for at least 12 mo for drug-eluting stents |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Prasugrel |

60 mg po once, followed by 10 mg po once/day |

Only for patients with ACS undergoing PCI Not used in combination with fibrinolytic therapy |

||||||||||||||||

|

Ticagrelor |

For patients undergoing PCI: 180 mg po once before the procedure, followed by 90 mg po bid |

— |

||||||||||||||||

|

Ticlopidine |

250 mg po bid |

Rarely used routinely because neutropenia is a risk and WBC count must be monitored regularly |

||||||||||||||||

|

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Abciximab |

Variable |

Some patients with ACS, particularly those who are having PCI with stent placement and high-risk patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI Therapy started before PCI and continued for 18 to 24 h thereafter |

||||||||||||||||

|

Eptifibatide |

Variable |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Tirofiban |

Variable |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Beta-blockers |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Atenolol |

50 mg po q 12 h acutely; 50–100 mg po bid long-term |

All patients with ACS, unless a beta-blocker is not tolerated or is contraindicated, especially high-risk patients; used long-term. Intravenous beta-blockers may be used in patients with ongoing chest pain despite usual measures, or persistent tachycardia, or hypertension in the setting of unstable angina and myocardial infarction. Caution is necessary in the setting of hypotension, or other evidence of hemodynamic instability. |

||||||||||||||||

|

Bisoprolol |

2.5–5 mg po once/day, increasing to 10–15 mg once/day depending on heart rate and BP response |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Carvedilol |

25 mg po bid (in patients with heart failure or other hemodynamic instability, the starting dose should be as low as 1.625–3.125 mg bid and increased very slowly as tolerated) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Metoprolol |

25–50 mg po q 6 h continued for 48 h; then 100 mg bid or 200 mg once/day given long term |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Calcium channel blockers |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Amlodipine |

5–10 mg po once/day |

Patients with stable angina if symptoms persist despite nitrates use or if nitrates are not tolerated |

||||||||||||||||

|

Diltiazem(extended-release) |

180–360 po once/day |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Felodipine |

2.5–20 mg po once/day |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Nifedipine(extended-release) |

30–90 mg po once/day |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Verapamil(extended-release) |

120–360 mg po once/day |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Statins |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Atorvastatin Fluvastatin Lovastatin Pravastatin Rosuvastatin Simvastatin |

Variable |

Patients with CAD to achieve a target LDL of 70 mg/dL (1.81 mmol/L) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Nitrates: Short acting |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Sublingual nitroglycerin(tablet or spray) |

0.3–0.6 mg q 4–5 min up to 3 doses |

All patients for immediate relief of chest pain; used as needed |

||||||||||||||||

|

Nitroglycerinas continuous IV drip |

Started at 5 mcg/min and increased 2.5–5.0 mcg every few minutes until required response occurs |

Selected patients with ACS: During the first 24 to 48 h, those with heart failure (unless hypotension is present), large anterior MI, persistent angina, or hypertension (BP is reduced by 10–20 mm Hg but not to < 80–90 mm Hg systolic) For longer use, those with recurrent angina or persistent pulmonary congestion |

||||||||||||||||

|

Nitrates: Long acting |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Isosorbide dinitrate |

10–20 mg po tid; can be increased to 40 mg tid |

Patients who have unstable angina or persistent severe angina and continue to have anginal symptoms after the beta-blocker dose is maximized A nitrate-free period of 8–10 h (typically at night) recommended to avoid tolerance |

||||||||||||||||

|

Isosorbide dinitrate (sustained-release) |

40–80 mg po bid (typically given at 8 amand 2 pm) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Isosorbide mononitrate |

20 mg po bid, with 7 h between 1st and 2nd doses |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Isosorbide mononitrate (sustained-release) |

30 or 60 mg once/day, increased to 120 mg or, rarely, 240 mg |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Nitroglycerinpatches |

0.2–0.8 mg/h applied between 6:00 and 9:00 am and removed 12–14 h later to avoid tolerance |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Nitroglycerinointment 2% preparation (15 mg/2.5 cm) |

1.25 cm spread evenly over upper torso or arms q 6 to 8 h and covered with plastic, increased to 7.5 cm as tolerated, and removed for 8–12 h each day to avoid tolerance |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Opioids |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Morphine |

2–4 mg IV, repeated as needed |

All patients with chest pain due to ACS to relieve pain (but ischemia may persist) Best used after drug therapy has been started or the decision to do revascularization has been made |

||||||||||||||||

|

Other drugs |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Ivabradine |

5 mg po bid, increased to 7.5 mg po bid if needed |

Inhibits sinus node. For symptomatic treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris in patients with normal sinus rhythm who cannot take beta-blockers

In combination with beta-blockers in patients inadequately controlled by beta-blocker alone and whose heart rate > 60 beats/min |

||||||||||||||||

|

Ranolazine |

500 mg po bid, increased to 1000 mg po bid as needed |

Patients in whom symptoms continue despite treatment with other antianginal drugs |

||||||||||||||||

|

*Clinicians may use different combinations of drugs depending on the type of coronary artery disease that is present. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

†Higher doses of aspirin do not provide greater protection and increase risk of adverse effects. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

‡Of low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs), enoxaparin is preferred. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

ACS = acute coronary syndromes; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD = coronary artery disease; LV = left ventricular; MI= myocardial infarction; NSTEMI =non–ST-segment elevation MI; PCI =percutaneous intervention; STEMI =ST-segment elevation MI. |

||||||||||||||||||

New drugs with novel mechanisms of action

- Ranolazine Hydrochloride – Ranolazine hydrochloride is a newer anti-ischemic agent approved in January 2006 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic stable angina. Ranolazine is a partial fatty oxidation inhibitor and is believed to exert its effects via altering the transcellular late sodium current and modulating the sodium-dependent calcium channels during myocardial ischemia, which in turn inhibits the calcium overload that causes myocardial ischemia.[Rx] By inhibiting the increase in intracellular calcium, ranolazine decreases the left ventricular diastolic tension and improves myocardial perfusion.[Rx] It is also believed to facilitate energy production in hypoxic cardiomyocytes by partially shifting cardiac lipid oxidation to glucose oxidation.[Rx]

- Dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine – agents have been shown to be equally efficacious as β-blockers in relieving angina and in improving exercise time to onset of angina or ischemia. In combination with β-blockers, they are effective in reducing angina symptoms.[Rx],[Rx]

- Clopidogrel bisulfate – is a thienopyridine derivative that irreversibly inhibits the binding of adenosine diphosphate to its platelet receptors, thereby affecting adenosine diphosphate–dependent activation of the glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. The Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events trial17 compared aspirin therapy with clopidogrel therapy in patients with previous myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. It demonstrated that clopidogrel was more effective than aspirin in decreasing the combined risk of myocardial infarction, vascular death, or ischemic stroke (absolute risk reduction, 0.51% per year; P = .043). Clopidogrel can be used in aspirin-intolerant patients, but its role in patients with chronic stable angina remains unknown.

- Lipid-Lowering Agents – The pooled data from various investigations suggest that every 1% reduction in total cholesterol reduces coronary events by 2%.18 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is an established risk marker for cardiovascular events.19 Statin treatment reduces the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular complications in primary and secondary prevention. Statins also possess anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects. Current data and guidelines advocate that the target for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be less than 70 mg/dL (to convert cholesterol

- lel-Arginine l-Arginine has been shown to increase coronary blood flow by improving endothelium-dependent vasodilation.[Rx ]Treatment with oral l-arginine increases exercise duration and maximum workload during stress testing and decreases the time to onset of ST-segment depression.[Rx–Rx]

- Nicorandil – Nicorandil is a nicotinamide ester that mimics nitrates in its activity, activates the mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels, and may offer ischemic preconditioning of the myocardium.[Rx]In the Impact of Nicorandil in Angina trial,[Rx] a total of 5,126 patients with stable angina were randomized to placebo or to nicorandil (20 mg twice daily). There were 398 (15.5%) primary end point events (nonfatal myocardial infarction, admission for cardiac chest pain, and death due to coronary heart disease) in the placebo group vs 337 (13.1%) in the nicorandil group (P = .014), representing a 17% relative risk reduction.

- Ivabradine – Ivabradine is a pure heart rate-lowering agent that reduces myocardial oxygen demand without negative inotropic effects[Rx] and lowers heart rate at rest and during exercise.[Rx] Ivabradine has demonstrated anti-ischemic and antianginal efficacy in randomized trials among patients having chronic stable angina pectoris compared with placebo as monotherapy[Rx] or when combined with atenolol.[Rx,Rx]

- Ranolazine – Ranolazine (approved recently by the US Food and Drug Administration) is a unique anti‐ischaemic drug that does not significantly affect hemodynamic parameters.[Rx] It was originally believed to modify the use of substrate by the ischaemic myocardium from lipids to glucose, thereby increasing metabolic efficiency. However, recent studies suggest that it inhibits the late sodium current INA and the accumulation of intracellular sodium and congruent cellular calcium overload via the sodium/calcium exchanger.

- Trimetazidine – Trimetazidine is a pure metabolic agent that induces the myocardium to shift from free fatty acids to predominantly glucose utilization in order to increase adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation per unit oxygen consumption. Efficacy studies reported that trimetazidine reduced ischemia during exercise stress tests, but there was no improvement in outcome. In a Cochrane meta‐analysis of 23 studies including 1378 patients, trimetazidine was associated with a significant reduction in weekly angina episodes and improved exercise time to 1 mm ST-segment depression compared to placebo.[Rx] In patients with stable angina who experienced concomitant erectile dysfunction, trimetazidine plus sildenafil was both safe and more effective in controlling episodes of ischemia during sexual activity than nitrates alone. These data indicate that trimetazidine is safe and effective for the treatment of symptoms of stable angina, either as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment.

- Nicorandil – Nicorandil exerts dual actions: it increases the opening of ATP‐gated K+ channels, thereby relaxing smooth muscle and contributing to coronary vasodilatation; and it has a nitrate‐donating moiety. Nicorandil may mimic the natural process of ischaemic preconditioning, which involves ATP‐dependent potassium channels. Several small randomized trials of patients with stable angina have shown that nicorandil prolongs the time to onset of ST depression and exercise duration during stress testing and improves myocardial perfusion at rest and with exercise. In the IONA trial of 5126 patients, the administration of nicorandil in addition to standard treatments reduced the primary endpoint (coronary death, MI, or hospitalization for angina) by 17% after a mean follow‐up of 1.6 years. There was also a significant reduction in the incidence of the acute coronary syndrome and all cardiovascular events.[Rx]

- Ivabradine – Ivabradine inhibits the If the channel in the sinus node, thereby causing bradycardia but without any negative inotropic effects. Double‐blind trials showed that ivabradine treatment increased exercise time to 1 mm ST-segment depression and limited angina compared to placebo, and had similar clinical effects to atenolol or amlodipine—namely, a two-thirds reduction in the number of anginal episodes and an increase in total exercise duration. Ivabradine offers clear therapeutic benefit for a whole range of patients with stable angina, including those with contraindication or intolerance to β‐blockers; however, its effect on survival remains to be explored.10

- Fasudil – Fasudil is an inhibitor of Rho kinase, an intracellular signaling molecule involved in the vascular smooth muscle contractile response. In patients with stable angina, fasudil treatment led to a significantly greater time to >1 mm ST-segment depression but showed no difference from placebo in decreasing the time to angina, the frequency of angina, or glyceryl trinitrate use.

- Molsidomine – Molsidomine is a nitric oxide-donating vasodilator. When compared with placebo, it reduced the incidence of anginal attacks and use of sublingual nitrates, and increased exercise capacity, in patients with stable angina. Higher doses provided better protection from angina, although hypotension was a side effect.

Drug Interactions

If you have angina, you and your doctor will develop a daily treatment plan. This plan should include:

- Medicines you regularly take to prevent angina

- Activities that you can do and those you should avoid

- Medicines you should take when you have angina pain

- Signs that mean your angina is getting worse

- When you should call the doctor or get emergency medical help

-

Encouragement of smoking cessation

-

Treatment of risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia)

In patients with CAD, efforts should be made to lower the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level (eg, with a statin). Current Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines are as follows :

-

In high-risk patients, a serum LDL cholesterol level of less than 100 mg/dL is the goal

-

In very high-risk patients, an LDL cholesterol level goal of less than 70 mg/dL is a therapeutic option

-

In moderately high-risk persons, the recommended LDL cholesterol level is less than 130 mg/dL, but an LDL cholesterol level of 100 mg/dL is a therapeutic option

-

Non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level is a secondary target of therapy in persons with high triglyceride levels (>200 mg/dL); the goal in such persons is a non-HDL cholesterol level 30 mg/dL higher than the LDL cholesterol level goal

Patients with established CAD and low HDL levels are at high risk for recurrent events and should be targeted for aggressive nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment. The currently accepted management approach is as follows:

-

In all persons with low HDL cholesterol levels, the primary target of therapy is to achieve the ATP III guideline LDL cholesterol level goals with diet, exercise, and drug therapy as needed

-

After the targeted LDL level goal is reached, emphasis shifts to other issues; in patients with low HDL and high triglyceride levels, the second priority is to achieve the non-HDL cholesterol level goal (30 mg/dL higher than the LDL goal); in patients with isolated low HDL cholesterol levels and triglyceride levels below 200 mg/dL, drugs to raise HDL can be considered

Short-acting nitrates

- Glyceryl trinitrate spray: droplets sprayed on or under the tongue are absorbed quickly from the mouth into the bloodstream and provide almost immediate relief

- Glyceryl trinitrate tablets: placed under the tongue to dissolve or chewed and left to dissolve in the mouth, the tablets are absorbed into the bloodstream from the lining of the mouth.

Long-acting nitrates

- Nitrate skin patches: provide a slow release of nitrate that is absorbed through the skin and provide the longest duration of effect of all the nitrate medications

- Nitrate tablets or capsules: provide nitrate that is absorbed through the stomach rather than the mouth and have a longer lasting effect than nitrate spray or tablets.

Other medications that may be prescribed to treat angina include beta-blockers which help the heart to pump more efficiently and calcium antagonists which widen the arteries and allow more blood to flow to the heart.

Other pharmacologic therapies that may be considered include the following:

-

Enteric-coated aspirin

-

Clopidogrel

-

Hormone replacement therapy

-

Sublingual nitroglycerin

-

Calcium channel blockers

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

-

Injections of autologous CD34+ cells

-

ACE inhibitors to lower blood pressure and protect your heart

- Beta-blockers to lower heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen use by the heart

- Calcium channel blockers to relax arteries, lower blood pressure, and reduce strain on the heart

- Nitrates to help prevent angina

- Ranolazine (Ranexa) to treat chronic angina

Revascularization therapy (ie, coronary revascularization) can be considered in the following:

-

Patients with left main artery stenosis greater than 50%

-

Patients with 2- or 3-vessel disease and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction

-

Patients with poor prognostic signs during noninvasive studies

-

Patients with severe symptoms despite maximum medical therapy

The 2 main coronary revascularization procedures are (1) percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, with or without coronary stenting, and (2) coronary artery bypass grafting. Considerations for choosing a procedure include the following:

-

Patients with 1- or 2-vessel disease and normal LV function who have anatomically suitable lesions are candidates for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and coronary stenting.

-

Drug-eluting stents can remarkably reduce the rate of in-stent restenosis

-

Patients with significant left main coronary artery disease, 2- or 3-vessel disease and LV dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, or lesions anatomically unsuitable for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty have better results with coronary artery bypass grafting

Other procedures that may be considered include the following:

-

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (in patients who continue to have unstable angina pectoris despite maximal medical treatment): This should be followed promptly by coronary angiography with possible coronary revascularization

-

Enhanced external counterpulsation (in patients whose angina is refractory to medical therapy and who are not suitable candidates for either percutaneous or surgical revascularization)

-

Laser trans myocardial revascularization (experimental)

-

Use of the Coronary Sinus Reducer (Neovasc Medical, Inc, Or Yehuda, Israel), a percutaneous implantable device designed to establish coronary sinus narrowing and elevate coronary sinus pressure (further studies needed)

Additional Tips

- Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth slowly when having chest pain. This will relax your body and provide more oxygen to your body.

- Drinking a glass of pomegranate juice can also help reduce pain in your chest.

- Take Coenzyme Q10 supplement after consulting a doctor to improve your heart’s energy efficiency and the supply of blood to your heart.

- Cook with extra-virgin olive oil as it boosts blood circulation in the body, making it an effective way to prevent chest pain.

- Eat slowly and in a relaxed manner as swallowing air can cause chest pain.

- Avoid extremely cold environments. Cold stimulates muscular reflexes that can cause chest pain.

- Eat well-balanced and nutritious meals rich in omega-3 fatty acids, folic acid, vitamin B12, and other nutrients.

- Avoid strenuous activities that cause chest pain and make it more acute.

- Reduce stress as it can worsen your condition. Avoid situations that make you upset or stressed.

- If you are overweight, take the necessary steps to lose weight.

- Limit the amount of alcohol and coffee you drink.

- Do not smoke or use other tobacco products.

- Control your blood pressure and blood sugar level with diet and medicine.

If your symptoms get worse or do not go away within a few minutes, even after your medication, call your doctor immediately as it could be a heart attack.

Home Remedies for Angina Pectoris

Many people use home remedies, which have been in use for many centuries. Some of these remedies are ideal for the treatment of angina as well as common heart problems. Angina is a very serious problem and you need to visit your doctor for treatment but you can follow these home remedies to support the treatment.

- Lemon – many people find that lemon juice is an effective treatment of angina. This is because lemon juice eliminates and stops cholesterol accumulation in the blood vessels.

- Garlic – this is a beneficial well-being food, which helps in the effective treatment of a variety of health problems including angina. This food also minimizes the effect of an angina attack on a patient.

- Grapefruit – This natural tonic improves the functions of the heart. Many people include grapefruits in their diet to help in curing angina.

- Basil leaves – many home remedies have basil leaves as a major ingredient. Basil leaves can also be used to make a remedy for angina pectoris. These leaves are chewable and may be taken in the morning. This may help an angina sufferer to minimize the effects of the disorder.

- Lemon with Honey – Take a glass of warm water and squeeze a half cut slice of lemon and add one teaspoon of honey. Mix it together and drink it before first thing in the morning.

- Onion – Onion juice is also very effective for angina suffering person. Take onion juice in the morning. It reduces bad cholesterol in the blood and helps to deliver proper blood supply to the heart.

- Parsley tea – Taking parsley tea or beetroot juice two times in a day is very effective in the treatment of angina.

- Diet Change – Increase fruits and vegetables in your daily diet as they are very essential to avoid any type of cardiovascular disease.

Homeopathic medicines of angina pectoris

The following homeopathic remedies more often administered for the treatment of angina pectoris:

- Aconite – unexpected episodes of angina with a sharp pain behind the sternum radiating to the left arm and shoulder, pulse big, rapid, bouncing and hard, severe agitation with congested sensation behind the sternum.

- Bryonia Alba – you can compare this pain to pins and needles with a scratching component inside the thoracic cage, intensified by any movements, and improved by relaxation while lying on the left side.

- Digitalis – feeling that the heart stops, and the heart rate diminishes. Digitalis patients report improvement at rest and deterioration of symptoms on movement.

- Lachesis – shooting chest pain, that radiates up to the throat. These patients never wear any turtleneck sweaters. Men hate ties. I will not administer Lachesis if a patient does not complain about bruises that suddenly appear on different parts of a body without any reason.

- Crataegus – chest pain radiating to the left clavicle. Pulse is weak and fast, arrhythmia, Fingernails and Toenails are bluish.

- Glonoinum – intense palpitation, which radiates in all direction and throbbing in head, torso, arms, and legs.

- Amyl nitrate – heart rate is fast accompanied with a sensation of a band around the head; breathing is difficult with the sensation of the spasm in the heart area.

- Naja – severe chest pain, radiating to the nape of the neck, heart rate is slow, arrhythmia, trembling and palpitation

- Spigelia – sharp chest pain with the feeling of compression behind the sternum radiates down the left arm to about the level of the pinky finger. Acts well in smokers and drunkards

- Arsenic album is an outstanding homeopathic medicine for angina pectoris with intense, excruciating chest pain. This pain aggravates in bed especially if an individual is lying face up. The pick of this pain usually takes place after 12 AM and especially between 1:00 AM and 3:00 AM.

- Cimicifuga – I would prescribe this homeopathic remedy to women only if patient reports sudden cease of heartbeat accompanied with intense chest pain. Traditionally Cimicifuga is a medicine for women who have some disorders in their reproductive system. The Materia Medica description of this medicine clearly states “Cherchez la femme” – a French expression for “look for the woman.” In my understanding of the homeopathic philosophy, this remedy will perfectly fit any forms of angina pectoris in a woman with GYN issues.

Veratrum album – is especially effective when heartbeat ceases in tobacco chewers. This symptom is usually co-existed by the hasty breath. - Lilium Tigrinum – severe chest pain radiates to the RIGHT arm (this is not a typo, RIGHT ARM is a special property for Lilium). Patients report a pounding feeling all over the body with the signs of choking. Considering a constitutional approach in homeopathic medicine, I prescribe Lilium Tigrinum only to sexually oriented women. Yes, this is a very important constitutional property for Lilium – these women love sex and always want it.

- Argentum Nitricum – very useful homeopathic drug for patients who report episodes of angina after a meal. Other constitutional properties for Argentum nitricum are very fast speech and sudden cravings for sweets.

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3922315/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4653970/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1994474/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1994448/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15860376

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16860010

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096292/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1547669/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angina

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/angina-pectoris

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/angina-pectoris

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/06/980623044903.htm

- https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/angina-chest-pain/angina-pectoris-stable-angina

- http://esciencenews.com/sources/science.daily/angina-pectoris-stable-angina

- https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/angina-chest-pain/angina-pectoris-stable-angina

- https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/heart-disease-angina

[/bg_collapse]