Abdominal Pain- Symptoms, Diagnosis is also known as stomach pain or tummy ache, is a common symptom associated with non-serious and serious causes. Common causes of pain in the abdomen include gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome. In a third of cases, the exact cause is unclear.

The pain of rapid onset begins with a few seconds and steadily increases in severity over the next several minutes. The patient will recall the time of onset in general but without the precision noted in pain of sudden onset. The pain of rapid onset is associated with cholecystitis, pancreatitis, intestinal obstruction, diverticulitis, appendicitis, a ureteral stone, and penetrating gastric or duodenal ulcer.

Anatomy of Abdominal Pain

The abdomen is divided into five sections. The location of the pain can sometimes help doctors tell whether the pain is worrisome or not. Here are the main regions:

- Upper right quadrant – The right upper quadrant contains the liver and gallbladder, which are protected by the lower right part of the ribcage. The large intestine, or colon, also spends a little time in this section.

- Upper left quadrant – The left upper quadrant contains part of the stomach and the spleen. The colon spends time here as well.

- Upper middle section – Between these two sections, in the upper middle of the abdomen, is a section known as the epigastrium. This is an important section because it contains most of the stomach, part of the small intestine, and the pancreas—all of which can cause pain.

- Right lower quadrant – This quadrant contains more colon and the last part of the small intestine, where the appendix resides. In women, one of the ovaries is in this section.

- Lower left quadrant – The other ovary lives in the left lower quadrant, along with the last part of the colon.

Types of Abdominal Pain

There are different types of abdominal pain depending on the structures involved.

- Visceral pain – comes from the organs within the abdominal cavity (which are called the viscera). The viscera’s nerves do not respond to cutting, tearing, or inflammation. Instead, the nerves respond to the organ being stretched (as when the intestine is expanded by gas) or surrounding muscles contract. Visceral pain is typically vague, dull, and nauseating. It is hard to pinpoint. Upper abdominal pain results from disorders in organs such as the stomach, duodenum, liver, and pancreas. Midabdominal pain (near the navel) results from disorders of structures such as the small intestine, the upper part of the colon, and appendix. Lower abdominal pain results from disorders of the lower part of the colon and organs in the genitourinary tract.

- Somatic pain – comes from the membrane (peritoneum) that lines the abdominal cavity (peritoneal cavity). Unlike nerves in the visceral organs, nerves in the peritoneum respond to cutting and irritation (such as from blood, infection, chemicals, or inflammation). Somatic pain is sharp and fairly easy to pinpoint.

- Referred pain – is pain perceived distant from its source (see Figure: What Is Referred Pain?). Examples of referred pain are groin pain caused by kidney stones and shoulder pain caused by blood or infection irritating the diaphragm.

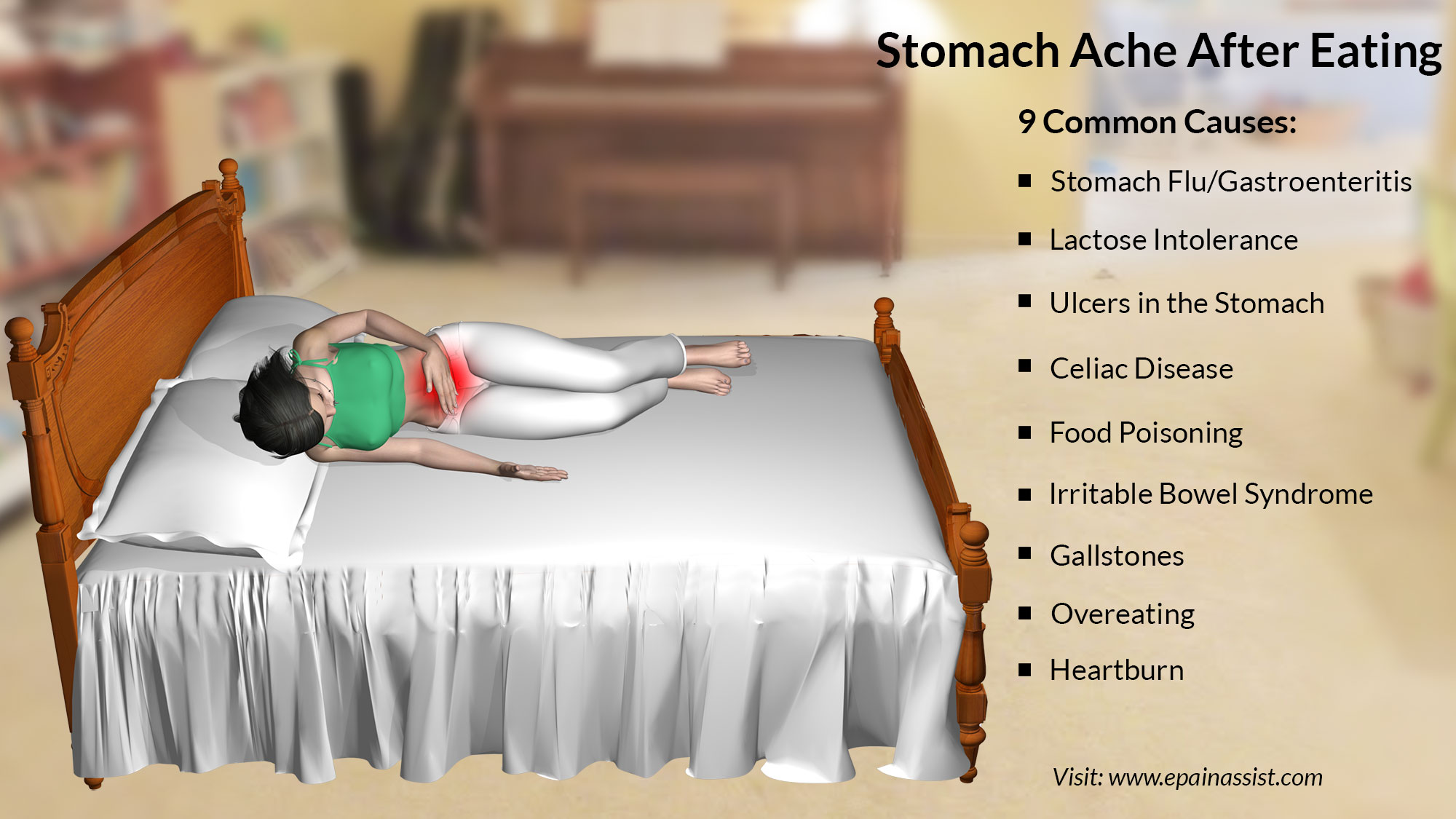

Causes of Abdominal Pain

Whether it is a mild stomachache, sharp pain or stomach cramps, abdominal pain has numerous. These include:

In children, the most common causes are

- Constipation

- Lactose intolerance (lactose is a sugar in dairy products)

- Stomach irritation (caused by aspirin or NSAIDs, cola beverages [acidity], and spicy foods)

- Liver disorders, such as hepatitis

- Gallbladder disorders, such as cholecystitis

- Indigestion

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Urinary tract infection

- Constipation

- Fever

- Inability to keep food down for several days

- Inability to pass stools, especially if you are also vomiting

- Vomiting blood

- Bloody stool

In young adults

Common causes include indigestion (dyspepsia) due to peptic ulcer or drugs such as aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Indigestion

- Constipation

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Appendicitis

- Stomach flu (viral gastroenteritis)

- Menstrual cramps

- Food poisoning

- Food allergies

- Wind

- Lactose intolerance

- Ulcers

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- A hernia

- Gallstones

- Kidney stones

- Endometriosis

- Crohn’s disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Urinary tract infection

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease ( GORD)

By Location

Upper middle abdominal pain

- Stomach (gastritis, stomach ulcer, stomach cancer)

- Pancreas pain (pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, can radiate to the left side of the waist, back, and even shoulder)

- Duodenal ulcer, diverticulitis

- Appendicitis (starts here, after some time moves to lower right abdomen)

Upper right abdominal pain

- Liver (caused by hepatomegaly due to fatty liver, hepatitis, or caused by liver cancer, abscess)

- Gallbladder and biliary tract (gallstones, inflammation, roundworms)

- Colon pain (below the area of the liver – bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer)

Upper left abdominal pain

- Spleen pain (splenomegaly)

- Pancreas

- Colon pain (below the area of spleen – bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer)

Middle abdominal pain (pain in the area around the belly button)

- Appendicitis (starts here)

- Small intestine pain (inflammation, intestinal spasm, functional disorders)

- Lower abdominal pain (diarrhea, colitis, and dysentery)

Lower right abdominal pain

- Cecum (intussusception, bowel obstruction)

- Appendix point (Appendicitis location)

Lower left abdominal pain

- diverticulitis, sigmoid volvulus, obstruction or gas accumulation

Pelvic pain

- bladder (cystitis, may be secondary to diverticulum and bladder stone, bladder cancer)

- pain in women (uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes)

Right lumbago and back pain

- liver pain (hepatomegaly)

- right kidney pain (its location below the area of liver pain)

Left lumbago and back pain

- less in spleen pain

- left kidney pain

Low back pain

- kidney pain (kidney stone, kidney cancer, hydronephrosis)

- Ureteral stone pain

Symptoms of Abdominal Pain

Symptoms that commonly occur with abdominal pain include back pain, chest pain, constipation, diarrhea, fever, nausea, vomiting, cough, and difficulty breathing. Characteristics of the pain (for example, sharp, cramping, radiating), the location of the pain within the abdominal area, and its relation to eating, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea are all factors associated with symptoms.

If your abdominal pain is severe or if it is accompanied by any of the following symptoms, seek medical advice as soon as possible:

- Inability to keep food down for more than two days

- Any signs of dehydration

- Inability to pass stool, especially if you are also vomiting

- Painful or unusually frequent urination

- The abdomen is tender to the touch

- The pain is the result of an injury to the abdomen

- The pain lasts for more than a few hours

- Bloating

- Belching

- Gas (flatus, farting)

- Indigestion

- Discomfort in the upper left or right; middle; or lower left or right abdomen

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease)

- Heartburn

- Chest discomfort

- Pelvic discomfort

- Loss of appetite

More serious symptoms include

- Severe pain

- Bloody stools

- Persistent nausea and vomiting

- Unintended weight loss

- Skin that appears yellow

- Severe tenderness when you touch your abdomen

- Swelling of the abdomen

Diagnosis of Abdominal Pain

A more extensive list includes the following:

Gastrointestinal

- Inflammatory – gastroenteritis, appendicitis, gastritis, esophagitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis

- Obstruction – a hernia, intussusception, volvulus, post-surgical adhesions, tumors, severe constipation, hemorrhoids

- Vascular – embolism, thrombosis, hemorrhage, sickle cell disease, abdominal angina, blood vessel compression (such as celiac artery compression syndrome), superior mesenteric artery syndrome, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Digestive – peptic ulcer, lactose intolerance, coeliac disease, food allergies

Glands

Bile system

- Inflammatory: cholecystitis, cholangitis

- Obstruction: cholelithiasis, tumors

Liver

- Inflammatory: hepatitis, liver abscess

Pancreatic

- Inflammatory: pancreatitis

Renal and urological

- Inflammation: pyelonephritis, bladder infection, indigestion

- Obstruction: kidney stones, urolithiasis, urinary retention, tumors

- Vascular: left renal vein entrapment

Gynecological or obstetric

- Inflammatory: pelvic inflammatory disease

- Mechanical: ovarian torsion

- Endocrinological: menstruation, Mittelschmerz

- Tumors: endometriosis, fibroids, ovarian cyst, ovarian cancer

- Pregnancy: ruptured ectopic pregnancy, threatened abortion

Abdominal wall

- muscle strain or trauma

- muscular infection

- neurogenic pain: herpes zoster, radiculitis in Lyme disease, abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES), tabes dorsalis

Referred pain

- from the thorax: pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis

- from the spine: radiculitis

- from the genitals: testicular torsion

Metabolic disturbance

- uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, porphyria, C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency, adrenal insufficiency, lead poisoning, black widow spider bite, narcotic withdrawal

Blood vessels

- aortic dissection, abdominal aortic aneurysm

Immune system

- sarcoidosis

- vasculitis

- familial Mediterranean fever

Idiopathic

- irritable bowel syndrome (affecting up to 20% of the population, IBS is the most common cause of recurrent, intermittent abdominal pain)

- Physical examination

- Laboratory tests — complete blood count (CBC), liver enzymes, pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase), pregnancy, and urinalysis tests

- Plain X-rays of the abdomen

- Radiographic studies

- Ultrasound

- Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen (this includes all organs and the intestines)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Barium X-rays

- Capsule endoscopy

- Endoscopic procedures, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD

- Colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests such as the complete blood count (CBC), liver enzymes, pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase), pregnancy test and urinalysis are frequently ordered.

- An elevated white count suggests inflammation or infection (as with appendicitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, or colitis).

- A low red blood cell count may indicate a bleed in the intestines.

- Amylase and lipase (enzymes produced by the pancreas) commonly are elevated in pancreatitis.

- Liver enzymes may be elevated with gallstone attacks or acute hepatitis.

- Blood in the urine suggests kidney stones.

- When there is diarrhea, white blood cells in the stool suggest intestinal inflammation or infection.

- A positive pregnancy test may indicate an ectopic pregnancy (a pregnancy in the fallopian tube instead of the uterus).

Plain X-rays of the abdomen

- Plain X-rays of the abdomen also are referred to as a KUB (because they include the kidney, ureter, and bladder). The KUB may show enlarged loops of intestines filled with copious amounts of fluid and air when there is an intestinal obstruction.

- Patients with a perforated ulcer may have air escape from the stomach into the abdominal cavity. The escaped air often can be seen on a KUB on the underside of the diaphragm. Sometimes a KUB may reveal a calcified kidney stone that has passed into the ureter and resulted in referred abdominal pain or calcifications in the pancreas that suggests chronic pancreatitis.

Radiographic studies

- Ultrasound – is useful in diagnosing gallstones, cholecystitis appendicitis, or ruptured ovarian cysts as the cause of the pain.

- Computerized Tomography (CT) of the abdomen – is useful in diagnosing pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, appendicitis, and diverticulitis, as well as in diagnosing abscesses in the abdomen. Special CT scans of the abdominal blood vessels can detect diseases of the arteries that block the flow of blood to the abdominal organs.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – is useful in diagnosing many of the same conditions as CT tomography.

- Barium X-rays – of the stomach and the intestines (upper gastrointestinal series or UGI with a small bowel follow-through) can be helpful in diagnosing ulcers, inflammation, and blockage in the intestines.

- Computerized Tomography (CT) of the small intestine – can be helpful in diagnosing diseases in the small bowel such as Crohn’s disease.

- Capsule Enteroscopy – uses a small camera the size of a pill swallowed by the patient, which can take pictures of the entire small bowel and transmit the pictures onto a portable receiver. The small bowel images can be downloaded from the receiver onto a computer to be inspected by a doctor later. Capsule enteroscopy can be helpful in diagnosing Crohn’s disease, small bowel tumors, and bleeding lesions not seen on x-rays or CT scans.

Endoscopic procedures

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD is useful for detecting ulcers, gastritis (inflammation of the stomach), or stomach cancer.

- Colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is useful for diagnosing infectious colitis, ulcerative colitis, or colon cancer.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is useful for diagnosing pancreatic cancer or gallstones if the standard ultrasound or CT or MRI scans fail to detect them.

- Balloon enteroscopy, the newest technique allows endoscopes to be passed through the mouth or anus and into the small intestine where small intestinal causes of pain or bleeding can be diagnosed, biopsied, and treated.

- Carnett’s sign – Abdominal wall tenderness can be caused by trauma, and with increasing numbers of patients on therapeutic anticoagulation, abdominal wall hematoma. The following technique, described by Carnett in 1926, may confirm the abdominal wall as the source of the patient’s pain. The point of maximal pain is identified, and this is palpated with the abdomen wall relaxed and then tensed through the performance of a half sit-up with the arms crossed. Increased pain with the wall tensed is a positive sign of abdominal wall pathology, a decrease in pain is considered a negative test. When prospectively applied in 120 patients, the test was positive in 24, with only one having an intra-abdominal pathologic condition.[Rx]Others have found it less accurate but still useful.[Rx] This test should not be routinely applied but is considered when there is a supportive history and absence of indicators of other illness.[Rx]

- Cough test – Originally described by Rostovzev in 1909, this test seeks evidence of peritoneal irritation by having the patient cough.[Rx] Jeddy and colleagues[Rx] described a positive test as a cough causing a sharp, localized pain. They applied this prospectively to patients with right lower quadrant pain and found it to have near perfect sensitivity with a specificity of 95% for the detection of appendicitis or peritonitis (one patient with perforated diverticulitis). Bennett and colleagues[Rx] consider signs of pain on coughing such as flinching, grimacing, or moving of hands to the abdomen as a positive test and reported a sensitivity of 78% with a specificity of 79% for the detection of peritonitis in a prospective study of 150 consecutive patients with abdominal pain.

- Closed eyes sign – Based on the assumption that the patient with an acute abdominal condition will carefully watch the examiner’s hands to avoid unnecessary pain, this test is considered an indicator of the nonorganic cause of abdominal pain. The test is considered positive if the patient keeps their eyes closed when abdominal tenderness is elicited. In a prospective study of 158 patients, Gray and colleagues[Rx] found that 79% of the 28 patients who closed their eyes did not have identifiable organic pathology.

- Murphy’s sign – Murphy described the cessation of inspiration in cholecystitis when the examiner curled their fingers below the anterior right costal margin from above the patient.[Rx] Now most commonly performed from the patient’s side, inspiratory arrest while deeply palpating the right upper quadrant is the most reliable clinical indicator of cholecystitis, although it only has a sensitivity of 65%.[Rx]

- The psoas sign – The psoas sign is provoked by having the supine patient lift the thigh against hand resistance, or with the patient laying on their contralateral side and the hip joint passively extended. Increased pain suggests irritation of the psoas muscle by an inflammatory process contiguous to the muscle. When positive on the right, this is a classic sign suggestive of appendicitis. Other inflammatory conditions involving the retroperitoneum, including pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, and psoas abscess, will also elicit this sign.

- The obturator sign – The obturator sign is elicited with the patient supine and the examiner supporting the patient’s lower extremity with the hip and knee both flexed to 90 degrees. The sign is positive if passive internal and external rotation of the hip causes reproduction of pain, and suggests the presence of an inflammatory process adjacent to the muscle deep in the lateral walls of the pelvis. Potential diagnoses include pelvic appendicitis (on the right only), sigmoid diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or ectopic pregnancy.

- The Rovsing sign – The Rovsing sign is a classic test used in the diagnosis of appendicitis. It is a form of indirect rebound testing in which the examiner applies pressure in the left lower quadrant, remote from the usual area of appendiceal pain and tenderness. The test is positive if the patient reports rebound pain in the right lower quadrant when the examiner releases pressure.[Rx] In limited studies, the psoas, obturator, and Rovsing signs demonstrate a low sensitivity (15%–35%) but a relatively high specificity (85%–95%) for appendicitis.[Rx],[Rx]

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3468117/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5075866/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK412/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1856631/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2904303/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/abdominal-pain

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2005290114001009

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090302133214.

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/12/071217100045.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3264926/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal_pain

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronic_functional_abdominal_pain

- https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/stomach-liver-and-gastrointestinal-tract/stomach-ache

- https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/abdominal-pain-in-adults

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318286.

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Pelvic_Pain.html?id=6q2xbQiHYWcC

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Chronic_Abdominal_Pain.html?id=8VuvBQAAQBAJ

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Abdominal_Pain.html?id=VC8pAAAAYAAJ

- https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/qa/what-are-other-possible-causes-of-abdominal-pain

[/bg_collapse]

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars