Stomach Cramping is one of the more common problems that may affect more than 90% of the population. The intensity of the pain may often scare us, but it is not necessarily due to something serious. However, lingering symptoms can indicate a chronic disease that should be treated. Sometimes, its intensity may seem pretty scary, but it does not necessarily mean that you are dealing with a serious health problem. However, oftentimes it indicates a chronic condition that you should treat.

Types of Stomach Ache

Acute Stomach Ache

Acute abdominal pain can be defined as severe, persistent abdominal pain of sudden onset that is likely to require surgical intervention to treat its cause. The pain may frequently be associated with nausea and vomiting, abdominal distention, fever and signs of shock. One of the most common conditions associated with acute abdominal pain is acute appendicitis.

Selected Causes

Traumatic

- Blunt or perforating trauma to the stomach, bowel, spleen, liver, or kidney

Inflammatory

- Infections such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, hepatitis, mesenteric adenitis, or a subdiaphragmatic abscess

- Perforation of a peptic ulcer, a diverticulum, or the caecum

- Complications of inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

Mechanical

- Small bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions caused by previous surgeries, intussusception, hernias, benign or malignant neoplasms

- Large bowel obstruction caused by colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, volvulus, fecal impaction or a hernia

- Vascular: occlusive intestinal ischemia, usually caused by thromboembolism of the superior mesenteric artery

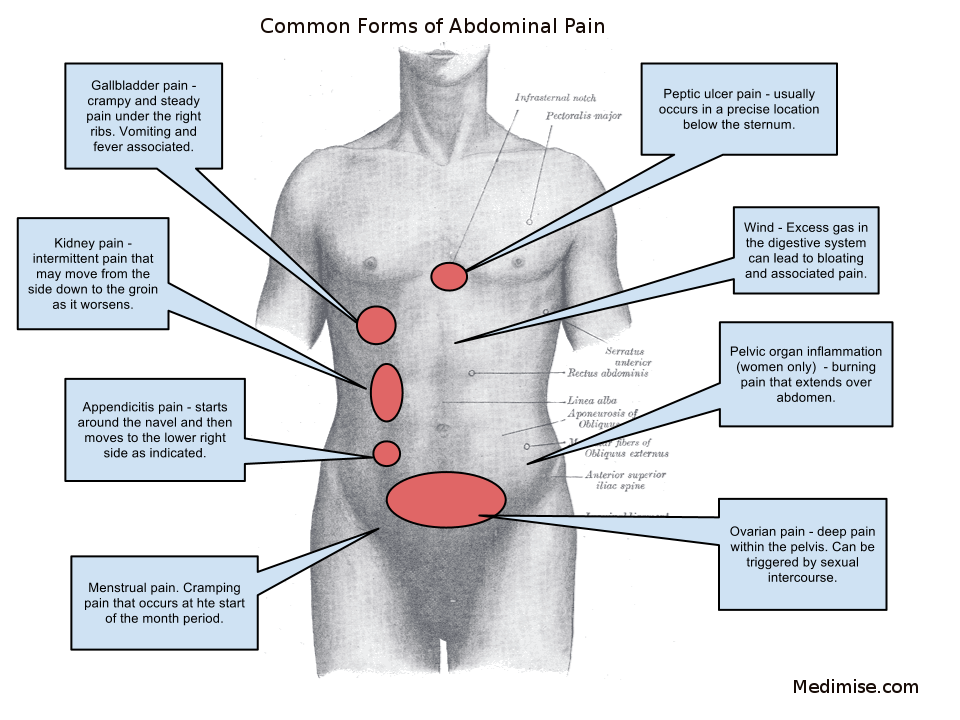

By location

Upper middle abdominal pain

- Stomach (gastritis, stomach ulcer, stomach cancer)

- Pancreas pain (pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, can radiate to the left side of the waist, back, and even shoulder)

- Duodenal ulcer, diverticulitis

- Appendicitis (starts here, after some time moves to lower right abdomen)

Upper right abdominal pain

- Liver (caused by hepatomegaly due to fatty liver, hepatitis, or caused by liver cancer, abscess)

- Gallbladder and biliary tract (inflammation, gallstones, worm infection)

- Colon pain (below the area of the liver – bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer)

Upper left abdominal pain

- Spleen pain (splenomegaly)

- Pancreas

- Colon pain (below the area of spleen – bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer)

Middle abdominal pain (pain in the area around the belly button)

- Appendicitis (starts here)

- Small intestine pain (inflammation, intestinal spasm, functional disorders)

- Lower abdominal pain (diarrhea, colitis, and dysentery)

Lower right abdominal pain

- Cecum (intussusception, bowel obstruction)

- Appendix point (Appendicitis location)

Lower left abdominal pain

- diverticulitis, sigmoid colon volvulus, obstruction or gas accumulation

Pelvic pain

- bladder (cystitis, may be secondary to diverticulum and bladder stone, bladder cancer)

- pain in women (uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes)

Right low back pain

- liver pain (hepatomegaly)

- right kidney pain (its location below the area of liver pain)

Left low back pain

- less in spleen pain

- left kidney pain

Low back pain

- kidney pain (kidney stone, kidney cancer, hydronephrosis)

- Ureteral stone pain

Differences in the location and rate of progression of lesions within the abdominal cavity may be summarized as outlined by Rx in terms of five possible components.

-

Visceral pain – alone is asymmetric pain located in the midline anteriorly, with or without associated vasomotor phenomena.

-

On occasion – when visceral pain is of rapid onset and of great severity, at the peak intensity of the pain it may “spill over” at the spinal cord level by viscerosensory and visceromotor reflexes into the corresponding cerebrospinal pathways, producing somatic findings without pathologic involvement of somatic receptors.

-

Visceral and somatic pain – often become combined as the causative lesion progresses from the viscus to involve adjacent somatic nerves. Visceral pain may continue, but a new and different pain is added.

-

Somatic pain – may be so severe that it overshadows the visceral pain of origin in the affected viscus, making an accurate diagnosis difficult.

-

Referred pain – due to irritation of the phrenic, obturator, and genitofemoral nerves are unique and diagnostically important findings remote from the abdomen that may provide clues to the source of abdominal pain.

The clinical significance of the pathways and stimuli responsible for the production of abdominal pain can perhaps best be appreciated by an analysis of the pathogenesis of acute appendicitis, as that disease process correlates with symptoms and physical findings common to that disorder.

Conditions such as continual bloating, frequent vomiting, diarrhea and blood in the stool, which persist for more than two weeks are signs that ask for immediate medical attention so that a more serious diagnosis is avoided.Abdominal pain can be any kind of discomfort felt between the chest and groin. Since this is an extensive area of the body, it is necessary to know the exact location of the pain so you can easier find the cause.

The evaluation of abdominal pain requires an understanding of the possible mechanisms responsible for pain, a broad differential of common causes, and recognition of typical patterns and clinical presentations. All patients do not have classic presentations.The map on the picture above will help you identify your pain.

Causes of Stomach Ache

Whether it’s a mild stomach ache, sharp pain, or stomach cramps, abdominal pain can have numerous causes. Some of the more common causes include:

- Indigestion

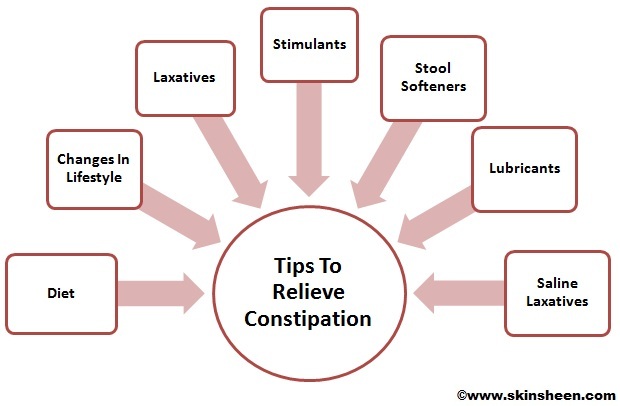

- Constipation

- Stomach virus

- Menstrual cramps

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Food poisoning

- Food allergies

- Gas

- Lactose intolerance

- Ulcers

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Hernia

- Gallstones

- Kidney stones

- Endometriosis

- Crohn’s disease

- Urinary tract infection

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Appendicitis

A more extensive list includes the following

The gastrointestinal> GI tract

- Inflammatory – gastroenteritis, appendicitis, gastritis, esophagitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis

- Obstruction – hernia, intussusception, volvulus, post-surgical adhesions, tumors, severe constipation, hemorrhoids

- Vascular – embolism, thrombosis, hemorrhage, sickle cell disease, abdominal angina, blood vessel compression (such as celiac artery compression syndrome), superior mesenteric artery syndrome, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Digestive – peptic ulcer, lactose intolerance, celiac disease, food allergies

Glands > Bile system

- Inflammatory: cholecystitis, cholangitis

- Obstruction: cholelithiasis, tumours

Liver

- Inflammatory: hepatitis, liver abscess

Pancreatic

- Inflammatory: pancreatitis

Renal and urological

- Inflammation: pyelonephritis, bladder infection, indigestion

- Obstruction: kidney stones, urolithiasis, urinary retention, tumors

- Vascular: left renal vein entrapment

Gynecological or obstetric

- Inflammatory: pelvic inflammatory disease

- Mechanical: ovarian torsion

- Endocrinological: menstruation, Mittelschmerz

- Tumors: endometriosis, fibroids, ovarian cyst, ovarian cancer

- Pregnancy: ruptured ectopic pregnancy, threatened abortion

Abdominal wall

- muscle strain or trauma

- muscular infection

- neurogenic pain: herpes zoster, radiculitis in Lyme disease, abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES), tabes dorsalis

Referred pain

- from the thorax: pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis

- from the spine: radiculitis

- from the genitals: testicular torsion

Metabolic disturbance

- uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, porphyria, C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency, adrenal insufficiency, lead poisoning, black widow spider bite, narcotic withdrawal

Blood vessels

- aortic dissection, abdominal aortic aneurysm

Immune system

- sarcoidosis

- vasculitis

- familial Mediterranean fever

Idiopathic

- irritable bowel syndrome (affecting up to 20% of the population, IBS is the most common cause of recurrent, intermittent abdominal pain)

Symptoms of Stomach Ache

If your abdominal pain is severe or recurrent or if it is accompanied by any of the following symptoms, contact your health care provider as soon as possible:

- Fever

- Inability to keep food down for more than 2 days

- Any signs of dehydration

- Inability to pass stool, especially if you are also vomiting

- Painful or unusually frequent urination

- The abdomen is tender to the touch

- The pain is the result of an injury to the abdomen

- The pain lasts for more than a few hours

These symptoms can be an indication of an internal problem that requires treatment as soon as possible. Seek immediate medical care for abdominal pain if you:

- Vomit blood

- Have bloody or black tarry stools

- Have difficulty breathing

- Have pain occurring during pregnancy

Doctors determine the cause of abdominal pain by relying on:

- Characteristics of the pain

- Physical examination

- Exams and tests

- Surgery and Endoscopy

Diagnosis of Stomach Ache

In order to better understand the underlying cause of abdominal pain, one can perform a thorough history and physical examination.

The process of gathering a history may include:

- Identifying more information about the chief complaint by eliciting a history of present illness; i.e. a narrative of the current symptoms such as the onset, location, duration, character, aggravating or relieving factors, and temporal nature of the pain. Identifying other possible factors may aid in the diagnosis of the underlying cause of abdominal pain, such as recent travel, recent contact with other ill individuals, and for females, a thorough gynecologic history.

- Learning about the patient’s past medical history, focusing on any prior issues or surgical procedures.

- Clarifying the patient’s current medication regimen, including prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, and supplements.

- Confirming the patient’s drug and food allergies.

- Discussing with the patient any family history of disease processes, focusing on conditions that might resemble the patient’s current presentation.

- Discussing with the patient any health-related behaviors (e.g. tobacco use, alcohol consumption, drug use, and sexual activity) that might make certain diagnoses more likely.

- Reviewing the presence of non-abdominal symptoms (e.g., fever, chills, chest pain, shortness of breath, vaginal bleeding) that can further clarify the diagnostic picture.

After gathering a thorough history, one should perform a physical exam in order to identify important physical signs that might clarify the diagnosis, including a cardiovascular exam, lung exam, thorough abdominal exam, and for females, a genitourinary exam.

Additional investigations that can aid diagnosis include:

- Blood tests including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, electrolytes, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, troponin I, and for females, a serum pregnancy test.

- Urinalysis

- Imaging including chest and abdominal X-rays

- Electrocardiogram

If the diagnosis remains unclear after history, examination, and basic investigations as above, then more advanced investigations may reveal a diagnosis. Such tests include

- Computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis

- Abdominal or pelvic ultrasound

- Endoscopy and/or colonoscopy

Differential diagnosis of Stomach Ache

The most frequent reasons for abdominal pain are gastroenteritis (13%), irritable bowel syndrome (8%), urinary tract problems (5%), inflammation of the stomach (5%) and constipation (5%). In about 30% of cases, the cause is not determined. About 10% of cases have a more serious cause including gallbladder (gallstones or biliary dyskinesia) or pancreas problems (4%), diverticulitis (3%), appendicitis (2%) and cancer (1%). More common in those who are older, mesenteric ischemia and abdominal aortic aneurysms are other serious causes.

Once an initial evaluation has been completed, your health care provider may have you undergo some tests to help find the cause of your pain. These may include stool or urine tests, blood tests, barium swallows or enemas, an endoscopy, X-ray, ultrasound, or CT scan.

| Acute abdomen (i.e., “peritonitis” abdomen, needing prompt surgical approach) |

| Appendicitis |

| Biliary colic and cholecystitis |

| Bowel obstruction |

| Diverticulitis |

| Extra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain (i.e., radicular pain, sickle cell disease, myocardial ischemia, pneumonia, among others) |

| Gastritis/peptic ulcer |

| Gastroenteritis |

| Gynecologic pain |

| Hernias |

| Iatrogenic pain (both drugs and surgery) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Liver disease (i.e., liver cirrhosis, hepatitis) |

| Nonspecific abdominal pain (NSAP) |

| Nonspecific abdominal pain in pregnant women |

| Oncologic pain |

| Others (i.e., all those conditions not precisely otherwise classified, such as sarcoidosis, adeno mesenteritis, muscle pain, overeating, alcohol and/or abuse substances, abdominal wall abscess or hematoma, vascular abdominal diseases) |

| Pancreatitis |

| Renal colic |

| Urinary tract infection and other urologic pain (i.e., testicular, prostatic) |

Differential Diagnosis of Abdominal Gas, Bloating, and Distention

|

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests such as the complete blood count (CBC), liver enzymes, pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase), pregnancy test and urinalysis are frequently ordered.

- An elevated white count suggests inflammation or infection (as with appendicitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, or colitis).

- A low red blood cell count may indicate a bleed in the intestines.

- Amylase and lipase (enzymes produced by the pancreas) commonly are elevated in pancreatitis.

- Liver enzymes may be elevated with gallstone attacks or acute hepatitis.

- Blood in the urine suggests kidney stones.

- When there is diarrhea, white blood cells in the stool suggest intestinal inflammation or infection.

- A positive pregnancy test may indicate an ectopic pregnancy (a pregnancy in the fallopian tube instead of the uterus).

Plain X-rays of the abdomen

Plain X-rays of the abdomen also are referred to as a KUB (because they include the kidney, ureter, and bladder). The KUB may show enlarged loops of intestines filled with copious amounts of fluid and air when there is an intestinal obstruction. Patients with a perforated ulcer may have air escape from the stomach into the abdominal cavity. The escaped air often can be seen on a KUB on the underside of the diaphragm. Sometimes a KUB may reveal a calcified kidney stone that has passed into the ureter and resulted in referred abdominal pain or calcifications in the pancreas that suggests chronic pancreatitis.

Radiographic studies

- Ultrasound – is useful in diagnosing gallstones, cholecystitis appendicitis, or ruptured ovarian cysts as the cause of the pain.

- Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen – is useful in diagnosing pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, appendicitis, and diverticulitis, as well as in diagnosing abscesses in the abdomen. Special CT scans of the abdominal blood vessels can detect diseases of the arteries that block the flow of blood to the abdominal organs.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – is useful in diagnosing many of the same conditions as CT tomography.

- Barium X-rays of the stomach and the intestines (upper gastrointestinal series or UGI with a small bowel follow-through) can be helpful in diagnosing ulcers, inflammation, and blockage in the intestines.

- Computerized tomography (CT) of the small intestine – can be helpful in diagnosing diseases in the small bowel such as Crohn’s disease.

- Capsule enteroscopy – uses a small camera the size of a pill swallowed by the patient, which can take pictures of the entire small bowel and transmit the pictures onto a portable receiver. The small bowel images can be downloaded from the receiver onto a computer to be inspected by a doctor later. Capsule enteroscopy can be helpful in diagnosing Crohn’s disease, small bowel tumors, and bleeding lesions not seen on x-rays or CT scans.

Endoscopic Procedures

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy – or EGD is useful for detecting ulcers, gastritis (inflammation of the stomach), or stomach cancer.

- Colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is useful for diagnosing infectious colitis, ulcerative colitis, or colon cancer.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is useful for diagnosing pancreatic cancer or gallstones if the standard ultrasound or CT or MRI scans fail to detect them.

- Balloon enteroscopy, the newest technique allows endoscopes to be passed through the mouth or anus and into the small intestine where small intestinal causes of pain or bleeding can be diagnosed, biopsied, and treated.

- Breath Testing Breath testing is the most widely used diagnostic test for SIBO. Breath testing is based on the principle that bacteria produce H2 and CH4 gas in response to nonabsorbed carbohydrates in the intestinal tract; H2 gas can then freely diffuse to the bloodstream, where it is exhaled by the patient. A carbohydrate load, typically lactulose or glucose, is administered to the patient, and exhaled breath gases are analyzed at routine intervals. With lactulose, a normal response would be a sharp increase in breath H2(and/or CH4) once the carbohydrate load passes through the ileocecal valve into the colon. In a normal small intestine, glucose should be fully absorbed prior to reaching the ileocecal valve; therefore, any peak in breath H2 or CH4 is indicative of SIBO. There is significant laboratory-to-laboratory variation as to what constitutes a positive breath test; generally, an increase in H2 of 20 parts per million within 60–90 minutes is considered to be diagnostic of SIBO.Rx Elevated fasting levels of H2 and CH4 have also been shown to be highly specific, but not sensitive, for the diagnosis of SIBO.Rx Earlier studies have demonstrated that 14–27% of subjects will not excrete H2 in response to varying loads of lactulose; however, these nonproducers of H2 were found to have significantly higher levels of CH4 after lactulose ingestion. Thus, the addition of CH4 analysis may increase the sensitivity of the H2 breath test.Rx

- Empiric Antibiotics A direct test for SIBO is an empiric course of antibiotics, an approach that is similar to a trial of proton pump inhibitors for patients with acid reflux symptoms. The use of empiric antibiotics is limited by their adverse effects, which include the potential to cause pseudomembranous colitis; however, these risks have decreased in recent years with the advent of poorly absorbable antibiotics such as rifampin (Xifaxan, Salix). Few trials to date have evaluated an empiric trial of antibiotics for SIBO, although this approach would be reasonable for any patient with symptoms consistent with SIBO and/or any condition that would predispose the patient to this condition (ie, scleroderma or previous surgery involving the ileocecal valve). Empiric antibiotic trials are not without risks, due to the potential for promoting drug resistance and other side effects, including nausea, abdominal pain, and upper respiratory infections. However, a number of studies have shown that rifaximin has rates of adverse effects that are similar to those associated with placebo.Rx

Treatment of Stomach Ache

Medications

Medications that may help in managing the signs and symptoms of nonulcer stomach pain include

- Over-the-counter gas remedies – Drugs that contain the ingredient simethicone may provide some relief by reducing gas. Examples of gas-relieving remedies include Mylanta and Gas-X.

- Medications to reduce acid production – Called H-2-receptor blockers, these medications are available over-the-counter and include cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR) and ranitidine (Zantac 75). Stronger versions of these medications are available in prescription form.

- Medications that block acid ‘pumps – Proton pump inhibitors shut down the acid “pumps” within acid-secreting stomach cells. Proton pump inhibitors reduce acid by blocking the action of these tiny pumps.

Over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole (Prevacid 24HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC). Stronger proton pump inhibitors also are available by prescription.

- Medication to strengthen the esophageal sphincter – Prokinetic agents help your stomach empty more rapidly and may help tighten the valve between your stomach and esophagus, reducing the likelihood of upper abdominal discomfort. Doctors may prescribe the medication metoclopramide (Reglan), but this drug doesn’t work for everyone and may have significant side effects.

- Low-dose antidepressants – Tricyclic antidepressants and drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), taken in low doses, may help inhibit the activity of neurons that control intestinal pain.

- Antibiotics – If tests indicate that a common ulcer-causing bacterium called H. pylori is present in your stomach, your doctor may recommend following drugs

- Aluminum Hydroxide and Magnesium Hydroxide – Aluminum Hydroxide and Magnesium Hydroxide contain antacids, prescribed for preventing ulcers, heartburn relief, acid indigestion, and stomach upsets. Aluminum Hydroxide and Magnesium Hydroxide neutralize acid in the stomach.

- Aztreonam – Aztreonam is monobactam antibiotic, prescribed for serious infections caused by susceptible gram negative bacteria like urinary tract infection, lower respiratory tract infection. It works by killing sensitive bacteria that cause infection.

- Budesonide – Budesonide is a corticosteroid, prescribed for inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, and also for breathing trouble.

- Cefuroxime axetil – Cefuroxime axetil is a semi synthetic cephalosporin antibiotic, prescribed for different types of infections such as lung, ear, throat, urinary tract, and skin.

- Dexlansoprazole – Dexlansoprazole is a proton pump inhibitor, prescribed for esophagitis and heartburn due to gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Famotidine – Famotidine is a histamine (H2-receptor antagonist), prescribed for an ulcer.

- Fenoverine – Fenoverine is an antispasmodic, prescribed for muscle spasms.

- Hyoscyamine – Hyoscyamine is an anticholinergic agent, used as a pain killer (Belladonna alkaloid). It blocks cardiac vagal inhibitory reflexes during anesthesia induction and intubation, used to relax muscles.

- Levofloxacin – Levofloxacin is prescribed for treating certain bacterial infections, and preventing anthrax. It is a quinolone antibiotic. It kills sensitive bacteria.

- Mepenzolate – Mepenzolate is an antimuscarinic agent, prescribed for the treatment of peptic ulcer combined with other medication. It decreases acid secretion in the stomach and controls intestinal spasms.

- Mesalamine(Mesalazine) – Mesalamine(Mesalazine) is an anti-inflammatory agent, prescribed for the induction of remission and for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis (inflammation of the colon).

- Nitrofurantoin – Nitrofurantoin is an antibiotic, prescribed for urinary tract infections.

- Rabeprazole – Rabeprazole is a proton pump inhibitor, prescribed for duodenal ulcer, gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Zollinger-Ellison (gastric acid hyper secretion) syndrome. It works by decreasing the amount of acid made in the stomach.

- Gabapentin – Gabapentin, and pregabalin are used in the treatment of a number of chronic pain syndromesRx These compounds bind with high affinity to α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels in areas of the central nervous system involved in pain signaling. Both gabapentin and pregabalin have been demonstrated to alter pain and sensory thresholds to rectal distension in IBS patientsRx They should, therefore, be considered as adjunctive therapies in patients with refractory symptoms.

- Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) – the most common type of psychotherapy employed for FGIDs, is based on the complex interactions between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The aims of CBT include learning better coping and problem-solving skills, identification of triggers and reduction of maladaptive reactions to them. Specific techniques can include keeping a diary of symptoms, feelings, thoughts, and behaviors; adopting relaxation and distraction strategies; using positive and negative reinforcement for behavior modification; confronting assumptions or beliefs that may be unhelpful; and gradually facing activities that may have been avoided. The American Academy of Pediatrics subcommittee on chronic abdominal pain recently concluded that CBT may be useful in “improving pain and disability outcome in the short term” [Rx].

- Relaxation – is usually used in conjunction with other psychosocial therapies with the goal of reducing psychological stress by achieving a physiological state that is the opposite of how the body reacts under stress [Rx]. A variety of methods can be employed with effects such as decreasing heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, muscle tension, oxygen consumption or brain-wave activity [Rx]. Abdominal or deep breathing stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system to increase feelings of calmness and relaxation. In progressive muscle relaxation, children are guided to systematically tense and relax each muscle group of the body. Patients are then encouraged to maintain attention on the relaxed feeling that results after tensing muscles. Guided imagery is a specific form of relaxed and focused concentration where patients are taught to imagine themselves in a peaceful scene to create an experience void of stress and anxiety. This can be combined with other relaxation techniques to produce a state of increased receptiveness to gut-specific suggestions and ideas, also known as ‘gut-directed’ hypnotherapy.

- Biofeedback – uses electronic equipment in combination with controlled breathing, hypnotic or relaxation techniques to generate a visual or auditory indicator of muscle tension, skin temperature or anal control, allowing the child to have external validation of physiological changes.

- Probiotics – Commensal bacteria of the GI tract are believed to play an important role in homeostasis, while alterations to these populations have been implicated in dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, abnormal colonic fermentation and immunologic activation [Rx]. This hypothesis has been further supported by reports of IBS triggered by gastrointestinal infections and antibiotic use, both of which can disrupt normal enteric bacteria, as well as the finding of significantly decreased populations of normal Lactobacillus and bifidobacteria in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS [Rx]. Probiotics commonly contain Lactobacillus, bifidobacteria or other living microorganisms thought to be healthy for the host organism when ingested in sufficiently large amounts. Probiotics may improve IBS symptoms by restoring the microbial balance in the gut through metabolic competition with pathogens, by enhancing the intestine’s mucosal barrier or by altering the intestinal inflammatory response [Rx]. Different methods, formulations, dosages and outcome measures have made it difficult to make conclusions about the efficacy of probiotics. A recent meta-analysis concluded that probiotics as a class appeared to be efficacious for adults with IBS, although the magnitude of benefit and most effective species, strain and dosing are not clear [Rx]. Data in pediatric studies have been equally conflicting. In a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, Bausserman et al. randomized 64 children with IBS according to Rome II criteria to receive either Lactobacillus GG (1 × 1010 colony forming units) or placebo twice daily for 6 weeks [Rx]. Patients had similar rates of abdominal pain relief regardless of treatment: 44% in the Lactobacillus GG group compared with 40% in the placebo group. There was no significant difference in other gastrointestinal symptoms, except for decreased perception of abdominal distension for patients receiving Lactobacillus.

- Antispasmodics – Antispasmodic medications, such as peppermint oil and hyoscyamine, are thought to be helpful for FAP and IBS through their effects on decreasing smooth muscle spasms in the GI tract that may produce symptoms such as pain. In a recent meta-analysis, antispasmodics as a class were superior to placebo in the treatment of adults with IBS [Rx]. There was a significant amount of variability among included studies in terms of antispasmodic preparation, measured outcomes, and overall methodological quality. Several agents included in the meta-analysis, such as otilonium, cimetropium, and pinaverium, are not currently available in the USA.

- Antidepressants – Antidepressants are among the most studied pharmacologic agents for FGIDs. Mechanisms of action are thought to include reduction of pain perception, improvement of mood and sleep patterns, as well as modulation of the GI tract, often through anticholinergic effects. A recent review of adult studies found that antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were beneficial for the treatment of FGIDs [Rx]. However, in the last few years, overall use of antidepressant medications in children and adolescents has been somewhat tempered by concerns for increased suicidal thoughts and/or behavior, especially after the US FDA issued formal ‘black-box’ warnings in 2004. A subsequent meta-analysis did not find evidence that these suicidal thoughts or behaviors led to an increased risk of suicide [Rx].

- Monoamine uptake inhibitors – such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, represent a newer group of antidepressant medications with effects on serotonergic and adrenergic pain inhibition systems. These medications have shown evidence of analgesia in patients with fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathy, but there have been no studies on the treatment of pediatric FGIDs [Rx].

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors – act by blocking uptake of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), increasing its concentration at presynaptic nerve endings. In addition to its CNS effects on mood and anxiety, SSRIs may also be beneficial for gastrointestinal complaints, since serotonin is an important neurotransmitter in the GI tract and greater than 80% of the body’s stores are located in enterochromaffin cells of the gut [Rx]. The exact role of serotonin in the GI tract has not been fully elucidated, but it has been implicated in the modulation of colonic motility and visceral pain in the gut.

- Tricyclic antidepressants – primarily act through noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways but also have antimuscarinic and antihistaminic properties. Anticholinergic effects on the GI tract in terms of slowing transit can be beneficial for patients with IBS characterized by diarrhea but may worsen constipation. Additional side effects include the potential for inducing cardiac arrhythmias, so evaluation for prolonged QT syndrome with a baseline ECG is recommended by the American Heart Association [Rx]. Owing to sedative properties, TCAs should be given at bedtime. The usual starting dose is 0.2 mg/kg and is increased to a therapeutic dose of approximately 0.5 mg/kg.

- Hyoscyamine and dicyclomine – are both considered antispasmodics owing to their anticholinergic effects on smooth muscle. Hyoscyamine has occasionally been used in children on a short-term basis for gastrointestinal symptoms of pain, but long-term use has been associated with anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, urine retention, blurred vision, tachycardia, drowsiness, and constipation. There have been no studies of either medication for pediatric FAP or IBS, but hyoscyamine was found to have consistent evidence of efficacy in an adult meta-analysis [Rx].

- Cyproheptadine – Cyproheptadine is a medication with multiple mechanisms, including antihistaminic, anticholinergic and antiserotonergic properties, as well as possible calcium channel blockade effects. It has been used in appetite stimulation and prevention of pain and vomiting in an abdominal migraine and cyclic vomiting syndrome. Sadeghian et al. studied the use of cyproheptadine in 29 children and adolescents (aged 4.5–12 years) diagnosed with FAP in a 2-week, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. At the end of the study, 86% in the cyproheptadine group had improvement or resolution of abdominal pain compared with 35.7% in the placebo group (p = 0.003) [Rx]. These results need to be confirmed with additional larger trials.

- Acid suppressants – Acid suppression agents, such as H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors, are among the most common medications that are used in children with abdominal pain. Famotidine was studied by See et al. in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of 25 children (aged 5–18 years) who met Apley’s criteria for RAP and reported symptoms of dyspepsia [Rx]. Children who met the criteria for IBS were excluded. Patients received famotidine 0.5 mg/kg per dose twice daily for at least 14 days, although the total treatment length was variable depending on symptom response. On a subjective global assessment scale, more patients reported improvement on famotidine (68%) versus placebo (12%). However, there was no significant difference between famotidine and placebo on quantitative measures of symptom frequency and severity. There have been no controlled studies on the use of proton pump inhibitors for FAP or IBS.

- Prokinetics – Prokinetic agents that stimulate gastrointestinal motility have been employed for patients with FGIDs, especially for conditions involving constipation or delayed gastric emptyings, such as IBS and functional dyspepsia [Rx]. Tegaserod is a serotonin agonist that induces acceleration of small bowel and colonic transit through activation of 5-HT4 receptors in the enteric nervous system. When combined with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, tegaserod was found to be more effective in alleviating abdominal pain and increasing the number of bowel movements in adolescents with constipation-predominant IBS compared with PEG 3350 alone [Rx]. However, owing to an increased rate of cardiovascular events in adults taking the medication, tegaserod was removed from the market in March 2007. Two other serotonin-based agents with actions upon the 5-HT3 receptor, alosetron, and cilansetron, were also shown to be effective for adults with diarrhea-predominant IBS, but complications of severe constipation, ischemic colitis and perforations prompted the withdrawal of these medications from the market in 2000 [Rx]. Dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists, such as metoclopramide and domperidone, improve gastric motility, but their use in pediatric FAP and IBS is limited by concerns for side effects including extrapyramidal reactions, drowsiness, agitation, irritability and fatigue [Rx]. Erythromycin, an antibiotic with motilin receptor agonist properties in the stomach at doses of 1–2 mg/kg per dose may also be helpful for symptoms of pain or dyspepsia, but there are no pediatric data to support its routine use in FAP or IBS [Rx].

- Loperamide – is an opioid receptor agonist that slows colonic transit by acting on myenteric plexus receptors of the large intestine. Although loperamide is commonly used for treating diarrhea and urgency in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS, adult studies have shown efficacy only against symptoms of diarrhea and not abdominal pain [Rx]. For patients with FAP or IBS associated with constipation, stool softeners and laxatives have been likewise employed. In the previously mentioned study of adolescents with constipation-predominant IBS conducted by Khoshoo et al., patients treated with PEG 3350 oral solution as sole therapy did have a significant increase in a number of bowel movements, but no improvement in abdominal pain [Rx].

- Several herbal preparations – including Chinese herbal medications, ginger, bitter candytuft monoextract and peppermint oil (which was discussed previously in this article) have been employed for the treatment of FGIDs. Bensoussan et al. found that adults with IBS who received Chinese herbal medications in a randomized double-blind trial of 116 patients had significant improvements in bowel symptom scores as rated by patients (p = 0.03) and by gastroenterologists (p = 0.001) when compared with placebo [Rx]. Patients receiving Chinese herbal medications also reported significantly higher overall scores on a global improvement scale. On the other hand, in a later study by Leung et al., traditional Chinese herbal medications were not found to be superior to placebo in terms of symptoms and quality of life in adult patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS [Rx].

- Acupuncture – also adapted from traditional Chinese medicine, is postulated to have effects on acid secretion, gastrointestinal motility and sensation of visceral pain, possibly mediated through the release of opioid peptides in the CNS and enteric nervous system. Two recent adult trials, however, did not find evidence to support the superiority of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture in the treatment of IBS [Rx]. There have been no studies using acupuncture to treat children with FAP or IBS. A small, noncontrolled study of 17 children with chronic constipation reported an increased frequency of bowel movements with true acupuncture compared with placebo acupuncture [Rx]. Massage therapy has been hypothesized to reduce excitation of visceral afferent fibers and possibly dampen central pain perception processing, but there are limited data on the usefulness of massage therapy for FAP or IBS.

- Behavior Therapy- Working with a counselor or therapist may help relieve signs and symptoms that aren’t helped by medications. A counselor or therapist can teach you relaxation techniques that may help you cope with your signs and symptoms. You may also learn ways to reduce stress in your life to prevent nonulcer stomach pain from recurring.

- Herbal supplements. Herbal remedies that may be of some benefit for nonulcer stomach pain include a combination of peppermint and caraway oil. These supplements may relieve some of the symptoms of nonulcer stomach pain, such as fullness and gastrointestinal spasms. Artichoke leaf extract may also reduce symptoms of nonulcer stomach pain, including vomiting, nausea and abdominal pain.

- Relaxation techniques. Activities that help you relax may help you control and cope with your signs and symptoms. Consider trying meditation, yoga or other activities that may help reduce your stress levels.

-

Osmotic Laxatives These agents, the most common of which is polyethylene glycol, improve symptoms of constipation. Rx One prospective study found that symptoms of bloating improved when patients with chronic constipation were treated with a polyethylene glycol solution. Rx These agents have not been studied in patients who complain predominantly of bloating.

-

Neostigmine – Neostigmine is a potent cholinesterase inhibitor that is used in the hospital setting to treat acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. In a prospective study of 28 patients with abdominal bloating who underwent jejunal gas infusion, intravenous neostigmine induced significant and immediate clearance of retained gas compared to placebo. Rx A randomized, placebo-controlled study using pyridostigmine in patients with IBS and bloating (n=20) demonstrated only a slight improvement in symptoms of bloating. Rx The small sample sizes of these studies and the need to use neostigmine in a carefully supervised setting limit the applicability of these results.

-

Cisapride – Cisapride is a mixed 5-HT3/5-HT2 antagonist and 5-HT4 agonist that was previously used to treat reflux, dyspepsia, gastroparesis, constipation, and IBS symptoms. Tfe drug was withdrawn from the US market in July 2000. In a study of FD patients, cisapride improved symptoms of bloating in some patients, although the benefits were not overwhelming.Rx Cisapride did not improve bloating in patients with IBS and constipation.Rx

-

Domperidone – Domperidone is a dopamine antagonist used to treat FD, gastroparesis, and chronic nausea. Rx–Although this drug may improve dyspeptic symptoms (including upper abdominal bloating) in some patients, its routine use in clinical practice is precluded by the absence of prospective, randomized, controlled studies evaluating its efficacy in patients with functional bloating.

-

Metoclopramide – Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist approved for treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Rx Patients with FD and gastroparesis frequently have symptoms of bloating. Rx One small study found that metoclopramide did not improve symptoms of abdominal distention in dyspeptic patients.Rx

- Tegaserod – Tegaserod is a 5-HT4 (serotonin type 4) receptor agonist that stimulates GI peristalsis, increases intestinal fluid secretion, and reduces visceral sensation. Rx In July 2002, this drug was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of IBS with constipation in women, as studies showed an improvement in bloating symptoms with the drug.Rx Although tegaserod has since been withdrawn from the US market, it is still available for emergency use. Other 5-HT4 agonists (ie, prucalopride) may become available in the United States in the future.

Chloride Channel Activators

- Lubiprostone – Two phase III studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of lubiprostone (Amitiza, Sucampo) in patients with IBS and constipation.Rx A total of 1,171 adults (91.6% women) who had been diagnosed with constipation-predominant IBS (based on Rome II criteria) were randomized to receive either 12 weeks of twice-daily lubiprostone (8 mcg) or placebo. The primary efficacy variable was a global question that rated overall IBS symptoms. Patients who received lubiprostone were nearly twice as likely as those who received placebo to achieve overall symptom improvement (17.9% vs 10.1%; P=.001). Secondary endpoints, including bloating, were significantly improved in the lubiprostone group compared to the placebo group (P<.05 for all endpoints). The most common treatment-related side effects were nausea (8%) and diarrhea (6%); these side effects occurred in 4% of the placebo group.

- Linaclotide – Linaclotide is a 14-amino-acid peptide that stimulates the guanylate cyclase receptor. Lembo and colleagues conducted a multicenter, placebo-controlled study of 310 patients with chronic constipation (based on modified Rome II criteria). Rx Patients were randomized to receive 1 of 4 linaclotide doses (75 µg, 150 µg, 300 µg, or 600 µg) or placebo once daily for 4 weeks. Patient measures of bloating were significantly better for all linaclotide doses compared to placebo. A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of 420 patients with constipation-predominant IBS (based on modified Rome II criteria; <3 complete spontaneous bowel movements [CSBMs]/week) compared daily linaclotide (75 µg, 150 µg, 300 µg, or 600 µg) to placebo during a 12-week study period. Rx The primary endpoint was the change in CSBM frequency, while other bowel symptoms (eg, abdominal pain and bloating) were secondary endpoints. A total of 337 patients (80%) completed the study. Using a strict intention-to-treat analysis, all doses of linaclotide were shown to significantly improve stool frequency (P<.023 or better) as well as improve symptoms of straining, bloating, and abdominal pain (all with P<.05, except for the 150-µg dose and bloating, which was not statistically better than placebo).

Home Remedies for Stomach Aches & Cramps

Stomach aches, also broadly called “abdominal pain,” are tricky things to find remedies for unless you know the cause. Ranging from indigestion and irritable bowel syndrome to gastritis and GERD, an aching tummy can stem from many things. Assuming you are dealing with an uncomplicated stomach ache, these remedies can help bring relief from the pain and discomfort that’s making you miserable.

1. Enjoy a Cup of Chamomile Tea

Chamomile can help ease the pain of a stomach ache by working as an anti-inflammatory (for example the lining of the stomach can become inflamed as a result common gastritis, caused by bacteria) and by relaxing the smooth muscle of the upper digestive track. When it relaxes that muscle, the contractions that are pushing food through your system ease up a bit and lessen the pain of cramping and spasms.

You will need

- 1 teabag of chamomile tea OR 1-2 teaspoons of dried chamomile

- A mug

- Hot water

Directions – Pour boiling water over a teabag and cover your mug, letting it steep for 10 minutes. If using dried chamomile, place 1-2 teaspoons in a mug and cover with boiling water. Cover the mug and let steep for 15-20 minutes. Sip slowly.

2. Use a “Hot” Pack

I put hot in quotations because you don’t truly want it hot-just very warm, but comfortably so. You can also use a hot water bottle for this as well. Heat helps to loosen and relax muscles, so if you find yourself cramping up, some warmth can go a long ways for relieving you of the dreadful discomfort.

You will need

- A hot pack, hot water bottle, or something similar

- A cozy place to lie down

Directions – Find a place to lie down, and rest the hot pack on your belly. It should be a comfortable temperature, but definitely warm. Do this for at least 15 minutes, or as long as you need to, reheating as necessary.

3. Rice Water

Rice water is exactly what it sounds like-the water left-over after you cook rice. It acts a demulcent, meaning a substance that relieves inflammation by forming a sort of soothing barrier over a membrane, in this case, the lining of your stomach.

You will need

- 1/2 cup of white rice

- 2 cups of water

- A pot

Directions – Cook your rice with twice the amount of water you normally would for your chosen amount. In this case, I am using plain old long-grain white rice. Put your rice in a pot on the stove and add the water, cooking over medium-low heat. As the rice starts to become tender, remove it from the heat and let it soak for 3 minutes with the lid on the pan. Drain and drink the water warm, adding a smidge of honey if needed. Save the rice for a bland meal later.

4. Enjoy Some Mint

Fresh peppermint tea (or just peppermint tea in general) can help relax stomach muscles. It also helps improve the flow of bile, which helps you digest properly. This is especially useful if suffering from indigestion or gas/bloating.

You will need

- A handful of fresh peppermint leaves OR 1-2 teaspoons dried

- Mug

- 1 cup water

Directions – Cover the peppermint with 1 cup of boiling water, cover, and let steep for 5-10 minutes. Sip slowly while it’s still toasty warm. If using the fresh peppermint leaves, you can chew on them as well to ease stomach pains. You can also just use a pre-made teabag if you find that more desirable.

5. Warm Lemon Water

Lemon water, if your issue is indigestion, helps a stomachache. The high acidity level stimulates the production of hydrochloric acid, which breaks down our food. By upping the amount of HCL being produced, you help move digestion along at a healthy pace. You get the added bonus of the hydration too, which keeps the system flushed and running smoothly.

You will need

- 1 fresh lemon

- warm water

6. Ginger Root Tea

Ginger contains naturally occurring chemicals called gingerols and shogaols. These chemicals can help relax smooth muscle, such as the muscle that lines the intestinal track, and therefore relieve stomach cramps or a colicky stomach ache. Ginger root is also great for relieving nausea, which may accompany a stomachache. Sipping on some warm tea can prove very useful as a home remedy for stomach aches and is, in my opinion, more effective than ginger ale.

You will need

- 1 ginger root, 1-2 inches

- A sharp knife or peeler

- 1-2 cups of water

- Honey (optional)

Directions – Wash, peel, and then grate or finely chop 1-2 inches of fresh ginger root. Bring 1-2 cups of fresh water to a boil (use less water and more ginger if you want a more concentrated drink) and add your ginger. Boil for 3 minutes and then simmer for 2 more. Remove from heat, strain, and add honey to taste. Sip slowly and relax.

7. Chew Fennel Seeds

Let’s say your stomach ache is being caused by indigestion. In this case, chewing fennel seeds will help as they contain anethole, a volatile oil that can stimulate the secretion of digestive juices to help move things along. It can also help tame inflammation, and reduce the pain caused by it. If you are suffering from gastritis, inflammation of the stomach, this may provide some relief from the discomfort.

You will need

- 1/2-1 teaspoon of fennel seeds

Directions – After a meal, chew ½-1 teaspoon of fennel seeds thoroughly. If you are pregnant, avoid fennel.

8. Drink Club Soda and Lime

Like lemon, lime can help ease an aching tummy. Combine the lime with club soda and you have an easy drink to sip on to wash away the pain. If you overate and have a stomach ache as a result, the carbonation in club soda will encourage you to burp, therefore relieving pressure in your belly. It has been shown to help greatly with dyspepsia (basically indigestion) and constipation.

You will need

- 8 ounces of cool club soda

- Fresh lime juice

Directions – Mix 8 ounces of club soda with the juice of half a lime. Stir and sip slowly.

I myself have had more than a few unfortunate run-ins with stomach aches, particularly this past year. Thanks to some generous family genes, I seem quite prone to them. Second, to headaches, I find chronic stomach pain to be one of the most distracting to deal with day-to-day. By keeping a couple options for stomach ache remedies on hand at all time, I find I can usually be prepared to ward it off should it start to creep up.

Precautions About Stomach Ache

- Apply heat on your abdomen for 20 to 30 minutes every 2 hours for as many days as directed. Heat helps decrease pain and muscle spasms.

Make changes to the food you eat as directed. Do not eat foods that cause abdominal pain or other symptoms. Eat small meals more often.

- Eat more high-fiber foods if you are constipated. High-fiber foods include fruits, vegetables, whole-grain foods, and legumes.

- Do not eat foods that cause gas if you have to bloat. Examples include broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower. Do not drink soda or carbonated drinks, because these may also cause gas.

- Do not eat foods or drinks that contain sorbitol or fructose if you have diarrhea and bloating. Some examples are fruit juices, candy, jelly, and sugar-free gum.

- Do not eat high-fat foods, such as fried foods, cheeseburgers, hot dogs, and desserts.

- Limit or do not drink caffeine. Caffeine may make symptoms, such as heart burn or nausea, worse.

- Drink plenty of liquids to prevent dehydration from diarrhea or vomiting. Ask your healthcare provider how much liquid to drink each day and which liquids are best for you.

Manage your stress. Stress may cause abdominal pain. Your healthcare provider may recommend relaxation techniques and deep breathing exercises to help decrease your stress. Your healthcare provider may recommend you talk to someone about your stress or anxiety, such as a counselor or a trusted friend. Get plenty of sleep and exercise regularly.

- Limit or do not drink alcohol. Alcohol can make your abdominal pain worse. Ask your healthcare provider if it is safe for you to drink alcohol. Also, ask how much is safe for you to drink.

- Do not smoke. Nicotine and other chemicals in cigarettes can damage your esophagus and stomach. Ask your healthcare provider for information if you currently smoke and need help to quit. E-cigarettes or smokeless tobacco still contain nicotine. Talk to your healthcare provider before you use these products.

Homeopathic medicines of Stomach Ache

- Arsenicum Album – The pain is burning, and is worse during the nighttime and when eating cold foods or sitting in cold weather. Vomiting, diarrhea, anxiety, restlessness, and weakness are present. You feel better with warmth and when drinking milk.

- Bryonia Alba – This is one of homeopathy’s best remedies for conditions striking the abdomen. The pains are sharp and stitching, occurring if you move even slightly, cough, or draw a deep breath. Better when lying still, especially on the painful side.

- Aconite – Useful when there are emotional symptoms such as fright, shock, fear, anxiety, and/or restlessness. Helpful for the pain that happens suddenly, after cold weather. Sneezing and jarring movements make it worse.

- Carcinosin – Mineral good for burning pain accompanied by hard, dry stools. You may be constipated and be craving sugary foods. Symptoms are worse in the late afternoon, and better when you put pressure on the stomach.

- Lycopodium – Good for pain on the right side, along with bloating and rumbling sounds. Cabbage, wheat, oysters, and onions tend to make things worse — as does the early evening. You feel better with loose clothing and warm drinks, and when passing gas.

- Belladonna – This common remedy battles those sharp stomach pains that strike and then disappear suddenly. The pain is worse with motion and better with steady pressure and when lying on the stomach.

- Chamomilla – This remedy’s hallmark symptom consists of irritability and anger caused by the pain. You experience bad cramps, have green diarrhea, and need to arch your back during painful spasms. The pain is worse at night, after eating, after coffee, and after an angry fit.

- Alumina – is an excellent remedy for very severe constipation in elderly people when the desire to open the bowels seems to have been lost. The individual may sit and strain and even feel impelled to use fingers to try to expel hard, knotty motions.

- Bryonia – is helpful for people who get constipated when they travel and who experience a burning sensation when they open their bowels in this constipated state.

- Calcarea carbonica – is useful in chubby people who paradoxically quite like the sensation of being constipated. They may lose the desire to open their bowels, but suffer no ill effects from it.

- Arsenicum album – is extremely useful in very neat, anxious, restless people. The diarrhea produces a burning sensation around the anus, which may become quite red and inflamed. The motions are usually watery and offensive.

- China – For cases which start in the early morning or just after midnight China is useful. The motions are watery with undigested residues present.

- Sulphur – is useful for people who are forced out of bed every morning, often at 5 or 6 am, by a sudden desire to open the bowels. The motions are loose and extremely offensive.

References

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ expand_text=”Show More” collapse_text=”Show Less” ]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK412/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3468117/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5075866/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1856631/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2904303/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/abdominal-pain

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2005290114001009

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090302133214.htm

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/12/071217100045.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3264926/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal_pain

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronic_functional_abdominal_pain

- https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/stomach-liver-and-gastrointestinal-tract/stomach-ache-

- https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/abdominal-pain-in-adults

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318286.php

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Pelvic_Pain.html?id=6q2xbQiHYWcC

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Chronic_Abdominal_Pain.html?id=8VuvBQAAQBAJ

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Abdominal_Pain.html?id=VC8pAAAAYAAJ

- https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/qa/what-are-other-possible-causes-of-abdominal-pain

[/bg_collapse]